If there was one thing Estes Kefauver’s Presidential campaigns were infamous for, it was their shoestring funding. Kefauver’s famous campaign technique of tromping through primary states and shaking the hand of every voter he could find was, in part, an act of necessity – he didn’t have the money to do much else.

During the 1956 campaign, though, a funny thing happened. After Kefauver scored surprise upset wins over Adlai Stevenson in New Hampshire and Minnesota… money started rolling in. Democratic donors, faced with the real possibility of Kefauver being the nominee, began sending some contributions his way.

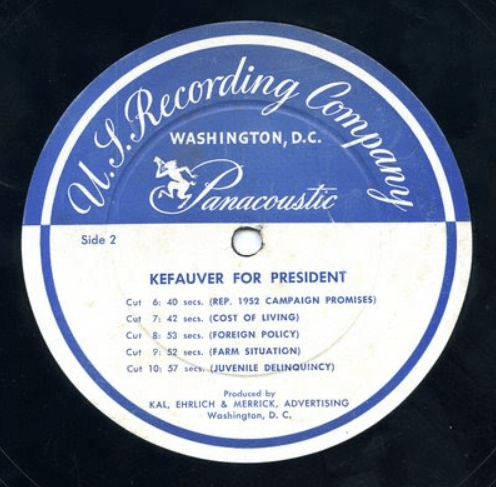

Suddenly flush with cash, the Kefauver campaign began investing in advertising. They hired the Washington ad firm Kal, Ehrlich, and Merrick to produce radio and TV ads for the campaign. (The firm, which had been around since 1922, is perhaps best known for creating the first version of Ronald McDonald, as portrayed by Willard Scott.)

In April 1956, Tait Trussell of the Washington Evening Star described the campaign ads as follows:

The newly recorded “commercials” are a far cry from the famous personal approach – an owlish smile, a firm handclasp and the modest salutation… The recordings open with a clanging bell. Then a purported farmer, businessman, or what-have-you asks a question on a current issue and the Senator replies, working in the “even break” whenever possible. The “commercials” close with a bid for funds.

Trussell mentioned that these “commercials” were being put on vinyl records that could be sent to radio stations and inserted into “a portfolio for key supporters to use where Mr. Kefauver can’t get close enough to touch or talk to a voter.”

The primary target for these ads was California, which closed out the Democratic primary calendar on June 5. As Trussell pointed out, the Golden State’s size and population made it a poor fit for the usual Kefauver handshaking approach: “Even so indefatigable a campaigner as he could not hope to shake the hand and personally beg the vote of more than a tiny percentage of the 13 million people there.”

The campaign hoped that these ads would give Kefauver a shot against Stevenson in this critical final primary (as well as the Florida primary that immediately preceded it).

As luck would have it, I recently came across a treasure trove: someone dug up one of the records with Kefauver ads, and digitized it. And once I found the ads, naturally I had to share them here.

Each of the ads follows the same format, as described by Trussell: After the ringing bell, a “typical” voter asks a question about a key campaign issue, which Kefauver answers. The “even break” slogan does indeed come up frequently, as you’ll see.

There are ten ads in all. Let’s go through them in the order they appeared on the record. We’ll cover the first five this week, and the last five in next week’s post.

The first ad is aimed at small businessmen:

This ad sets up a theme that will recur frequently in these ads: the Eisenhower administration looks out for big business, but ignores the needs of the average American. The questioner makes sure to shoehorn the campaign slogan right into the question: “You think they’re giving the little fella an even break?” (Hilariously, Kefauver sounds slightly annoyed to be asked, replying “Well, of course I don’t think they are.”)

After a somewhat anodyne statement about how big business is thriving under Ike while small business suffer, Kefauver makes a much bolder proclamation: if Eisenhower’s policies are continued for another term, “we may find ourselves with an economic super-state too powerful to be controlled.” (Somewhere, Bernie Sanders is pumping his fist.)

Kefauver concludes by saying, “If I’m elected President, I pledge that my administration will have only one policy: an even break for the average man.” As appealing as that idea is, I certainly hope the Kefauver administration would also have other policies. (Fortunately, the other ads suggest that he would.)

The second ad deals with the problems of family farmers:

Both Stevenson and Kefauver talked a good deal about farm issues in 1956, because of the broad unpopularity of Eisenhower’s Secretary of Agriculture, Ezra Taft Benson. Benson’s ideological opposition to farm price supports made him a villain to small farmers, who were struggling with falling prices and increasing competition from agribusiness concerns. They found Benson’s sermons on self-reliance obnoxious and tone-deaf.

Kefauver’s proposal here was standard Democratic doctrine at the time: fixed price supports at 90% of parity (that is, the prices that farmers received in the pre-World War I era), and 100% parity price support for small farmers. He also supports the government buying up surplus crops to feed the hungry both at home and overseas. This would not only help feed the hungry, but it would also help prop up farm prices without forcing farmers to cut production.

One other note: In both this and the previous ad, the questioner uses less than perfect English. (The small businessman in the first ad asks about the “little fella,” while the farmer in this ad mentions “things we gotta buy.”) This was clearly a deliberate choice, to show that Kefauver is the candidate of the average American, who doesn’t speak textbook English.

Contrast with Stevenson, who always used precise, perfect diction when lecturing voters about his views. You couldn’t imagine a Stevenson ad featuring voters saying words like “fella” and “gotta.” (If Stevenson would even include voters asking questions in his ads, which was unlikely to begin with.)

The third ad takes on the so-called “Eisenhower prosperity”:

In some ways, this is a rehash of the first ad, but with a crucially different spin. One of Eisenhower’s primary re-election talking points was that the country prospered on his watch. Kefauver here offers a different take: corporate executives and Wall Street fat cats may have prospered, but not small businessmen and regular people.

Kefauver rarely includes statistics in these ads, but he includes one here, saying that 30 % more small businesses failed in 1955 than in the prior year. (Republicans generally countered that this was because more small businesses started in 1955 than the year before.)

Kefauver concludes by promising that if he is elected, “bold action will be taken to stop the trend toward monopoly and to preserve the economic liberties upon which our political liberties are founded.” Like Elizabeth Warren and the “neo-Brandeisian” progressives today, Kefauver believed that allowing corporations to amass too much economic power was dangerous because they would then take political power away from the people.

The fourth ad takes on Ike’s foreign policy:

Interestingly, the questioner in this ad is a woman, who asks whether Kefauver thinks the administration “has lived up to its promises of a strong and dynamic foreign policy?” Unsurprisingly, Kefauver does not think so.

Without mentioning Secretary of State John Foster Dulles by name, Kefauver attacks Dulles’ strategies of brinksmanship and massive retaliation, saying that “Republicans have substituted bluff, bluster, and blunder for responsibility in our foreign affairs.” He argues that Dulles’ belligerence has cost America prestige and alienated allies. (I can only imagine what he’d say about the hyperaggression of our current foreign policy, which makes Dulles look like a pacifist in comparison.)

In lieu of the Dulles school of saber-rattling, Kefauver calls for a return of “the sort of imaginative leadership” practiced by FDR and Truman, which produced NATO, the Marshall Plan, and the Point Four program. In short, Kefauver’s foreign policy would focus on getting closer to our allies instead of scaring the hell out of our enemies.

The fifth ad discusses Kefauver’s beloved TVA, but from a different angle than usual:

The questioner nods towards Kefauver’s “fight against Republican giveaways of public power,” but rather than push for expanding public power to other states (a highly controversial proposition), the questioner instead asks about flood control. This may seem like a non sequitur, but remember that one of TVA’s original goals was to reduce flooding along the Tennessee River.

Kefauver wisely notes that, instead of just providing relief for flood victims, we should be trying to prevent floods from happening in the first place. He promises to “inaugurate forward-looking projects which will add a great deal to your state in irrigation, power production, and flood control.” In other words, he wants to create TVA-like projects in other states. Interestingly, however, he doesn’t say “TVA” in this ad anywhere, likely because he understood that the agency was a political football.

That completes the review of the first half of the ads. Next week, we’ll flip the record over and listen to the other side.

Leave a comment