Recently, the Republican Party, at the urging of President Donald Trump, voted to allow for a convention to be staged before the 2026 midterm elections.

At first blush, this might seem like a strange idea. The party will not select any nominees at this convention, so what’s the point of it, other than soothing Trump’s enormous ego?

However, the idea of a midterm convention isn’t new. Estes Kefauver proposed them back in 1952. He suggested that such conventions spotlight up-and-coming political stars and potential Presidential candidates. He also felt the parties could use them to develop policies on issues that arise between Presidential election cycles.

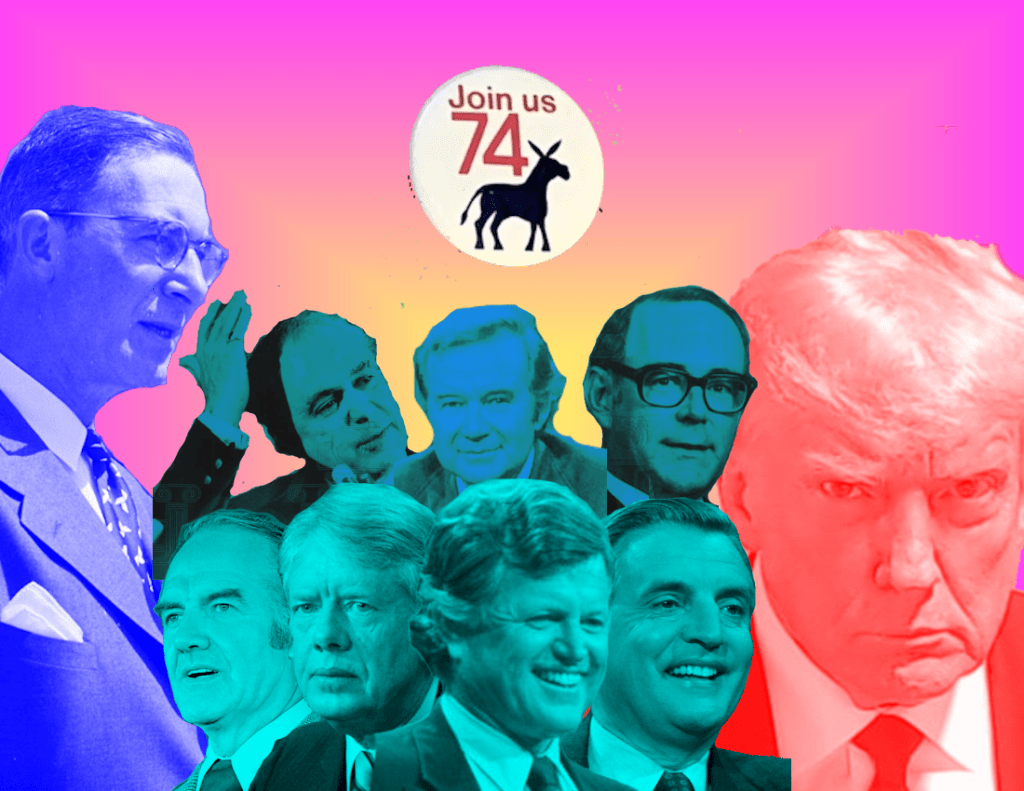

Kefauver’s suggestions were ignored at the time, but the Democrats did eventually adopt the concept, holding a series of them between 1974 and 1982. Though largely forgotten today, Democrats’ experience with those “mini-conventions” offers some cautions for today’s Republicans. Far from creating unity, the midterm convention might just highlight existing fractures within the party.

1974: Regulars and Reformers Brawl in KC

Democratic reformers of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s wanted to give more power to the people, just as Kefauver had championed. After the stormy 1968 convention, the Democrats convened the McGovern-Fraser Commission, which revamped the presidential nomination process, giving a greater role to rank-and-file voters.

At the 1972 convention, the reformers secured additional changes. One was a commission to draft a party charter. In addition, the delegates voted to hold a midterm convention in 1974.

The primary goal of the mini-convention, held in Kansas City, was to finalize the party charter, but reformers also hoped to adopt a platform for the midterm elections.

There was just one problem: the regulars and reformers couldn’t stand each other.

Old-line party bosses, led by George Meany and the AFL-CIO, resented the reformers for saddling the party with McGovern in ‘72. Meanwhile, the reformers suspected that the regulars planned to rig the new charter to maintain control of the party.

DNC Chairman Robert Strauss grew increasingly nervous that the mini-convention would turn into a free-for-all. With that in mind, he tried to lower the stakes.

He scheduled the gathering in December, after the midterms. He persuaded the DNC to limit the agenda solely to approving the charter, avoiding discussion of national issues.

Even with the scope of the convention narrowed, factional hostility persisted. “Democrats preparing for their national charter conference,” wrote the New York Times’ Christopher Lydon in mid-October, “have begun to take sides, as if by an unshakable habit, across the great divide that has split the party[.]”

The primary dispute over the charter concerned Section 10, the procedure for selecting convention delegates. Reformers wanted the ability to challenge states’ delegate selections if they didn’t include enough women and minority groups. Meanwhile, state party chairs worried that the charter’s insistence on representation at all levels would lead, in Lydon’s words, to “involvement of the national party’s enforcement machinery in village fund-raising raffles.”

The final draft of the charter provided the ability to challenge delegate selections, but placed the burden of proof on the challenger. This compromise didn’t satisfy the reformers, who walked out of the final planning meeting for the mini-convention in protest.

Strauss called an emergency meeting in mid-November to arrange a truce, which was only partially successful. The chairman worried that floor fights might unravel the careful compromises he’d negotiated to get the charter finalized.

In short, everybody came in expecting a war. Including McGovern, whose keynote address seemed designed to inflame the reformers.

“The forces of privilege will oppose reform as they always have,” he argued. “But to avoid issues is to invite disaster. Our survival as a party is at stake. The people will no longer accept a politics whose only purpose is power.”

Ex-North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford, who presided over the convention, gave voice to the question in everyone’s mind: “Can the Democratic Party eliminate the squabbles that have caused us to lose?”

In the end, the worst was avoided. After days of intense negotiation and a threatened walkout by a group of black delegates, the convention reached a compromise.

The clause placing the burden of proof on those challenging delegate selections was dropped. Instead, the charter called for “affirmative action” on the part of party leaders to guarantee the full participation of women and minority groups.

Despite originally planning not to discuss issues, the delegates also adopted a “Statement of Economic Policy” that called for national health insurance, an expansion of public-service jobs, tax cuts for low- and middle-income families, easier access to credit for struggling businesses, and stronger antitrust laws.

The convention heard from several aspiring 1976 Presidential candidates including Sanford, Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter, Texas Sen. Lloyd Bentsen, Washington Sen. Scoop Jackson, Arizona Rep. Mo Udall, and the infamous George Wallace (who rolled through the hall in his wheelchair shouting, “Make way for the front-runner!”).

Despite the tense negotiations, the delegates felt a sense of triumph when all was done. The Times’ R.W. Apple, Jr. reported that the proceedings “adjourned in euphoria with comments of self-congratulation, unity, and unbounded relief.” Time magazine added that the convention “turned into a virtual love feast.”

“I took my best shot today,” said a satisfied Strauss, “and I think we did well.”

The party got a perfect symbol of its newfound unity when Jesse Jackson shook hands with Chicago Mayor Richard Daley as the convention wound up.

Unfortunately, that euphoria quickly faded; what lingered was the bad blood between reformers and conservatives. The battle for control of the party was far from finished.

1978: Jimmy Sings the Blues in Memphis

There were enough positives from Kansas City that the ’76 convention voted to hold another mini-convention in 1978. This time, they’d gather as the party in power behind President Carter.

Unfortunately, the DNC was drowning in debt after the ’76 election. One of the key reasons they chose to hold the mini-convention in Memphis was that the city pledged $150,000 in cash and free services. (They hoped the event would boost their struggling downtown.)

In another cost-cutting move, the DNC downsized the gathering. After having nearly 2,000 delegates in 1974, the Memphis mini-convention would include just over 1,600.

Concerns about the event weren’t only financial. President Carter’s popularity was at a low ebb in early 1978, and the administration worried that his liberal critics would use the mini-convention to attack him, particularly on his proposed spending cuts and lukewarm support for a national health insurance program.

With that in mind, the ’78 gathering was again postponed until December, after the midterms. In addition, the administration worked closely with new party chairman John C. White to limit the opportunities for mischief from liberal dissenters.

The mini-convention would include two dozen issue workshops, after which the delegates would vote on resolutions adopting official positions. But the resolutions were pre-cleared in advance with White, crafted to display support for administration policies. If anti-Carter forces wanted to put forth their own resolutions, they’d need to gather enough signatures to force them to the floor.

Due to the general lack of enthusiasm – or because there wasn’t a nomination up for grabs in 1980 – many prominent Democrats declined to attend. Senators McGovern, Scoop Jackson, Robert Byrd, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Sam Nunn, Frank Church, and Ed Muskie all took a pass, as did Govs. Jerry Brown of California and Hugh Carey of New York.

“Our turndown list reads like a Who’s Who of American politics,” quipped staffer Elaine Kamarck.

The delegates who did show up were, in the words of the Times’ Douglas Kneeland, “quieter and less seasoned” than in previous cycles. DNC political director John Rendon estimated that at least half the delegates were first-timers.

Carter showed up, of course, along with Vice President Walter Mondale and a delegation of Cabinet members and senior White House and OMB staffers. (Most of them paid for their own travel, to spare the cash-strapped DNC.) They handed out green-and-white “Carter-Mondale ‘80” buttons.

One other big-name Dem who attend was Ted Kennedy, the idol of the party’s liberals. There were already whispers that the Senator from Massachusetts might consider challenging Carter in 1980. Although he was officially there for the panel on national health insurance, most of the mini-convention’s excitement revolved around what he might say in his speech.

Carter delivered the keynote address. He called the Democrats “a party of practical dreamers” and defended his administration’s record in making the government more ethical and efficient. “We Democrats are trying to make government competent so that it can be truly compassionate,” Carter said, “and we will achieve both those goals together, competence and compassion.”

On paper, it was a fine speech. But the reaction in the hall was rather tepid.

Kennedy got a much different reception. His soaring oration declared it was time for all Americans to have access to quality health care. “[A]s long as I have a voice in the United States Senate,” he thundered, “it’s going to be for that Democratic platform plank that provides decent quality of health care north and south, east and west, for all America as a matter of right and not a privilege.”

Kennedy also slyly turned his remarks into a critique of Carter’s leadership. “[W]e must have genuine leadership by the Democratic Party,” Kennedy argued. “Sometimes a party must sail against the wind” by fighting for what is right, he said, not just what’s currently popular.

His speech brought the delegates to their feet with cheers and boisterous applause. Speaking to reporters afterward, Kennedy insisted that he had no plans to challenge Carter for the nomination, but proclaimed that “I’m going to speak out on these issues and [Carter] understands that.”

(If you’re wondering what Carter thought about the speech, he wasn’t around to hear it. He left town before Kennedy arrived.)

The grim news for the administration continued. Liberal delegates pushed for a resolution demanding that he abandon his planned domestic spending cuts and attacking his proposed increase in defense spending. White and the party leaders managed to thwart that resolution, but the official resolution supporting Carter’s economic policies was opposed by 40 percent of the delegates.

In short, despite the administration’s attempt to stage-manage it, the Memphis mini-convention showed that there was broad unhappiness with Carter within the party, and that Kennedy lurked as a major threat. Anyone who paid attention in 1978 shouldn’t have been surprised when Kennedy made a play for the nomination at the 1980 convention.

1982: Third Time’s the Charm?

After the stormy mini-conventions in ’74 and ’78, you couldn’t blame the Democrats if they decided to scrap the idea altogether. But the 1980 convention passed a resolution calling for another midterm gathering in 1982.

Party leaders pushed new DNC chairman Charles Manatt to cancel it, but he insisted that he was bound by the resolution. However, he did his best to make sure this midterm convention – to be held in Philadelphia – wouldn’t be like the last two.

For one thing, he refused to call it a “convention,” instead referring to it as a “national party conference.” Instead of describing the attendees as “delegates,” Manatt called them “participants.” There were also a lot fewer of them; just 897 “participants,” barely more than half the size of the gathering in Memphis four years earlier. He also scheduled it for June, prior to the midterms.

Manatt ensured that the rules prevented the gathering from becoming “becoming a playground for activists passing far-out resolutions,” reported David Broder of the Washington Post. Instead of permitting resolutions from the floor, the seven issue-themed panels would produce reports, which the participants could vote to accept at the end of the event.

Since the Democrats were out of power, the gathering was once again popular among aspiring Presidential contenders. The roster of speakers included Mondale, Kennedy, and Sens. Alan Cranston of California, Fritz Hollings, Gary Hart of Colorado, and John Glenn of Ohio, all potential ’84 candidates. (Florida Gov. Reubin Askew was offered a slot but declined.)

As Manatt prepared the program, he faced one key issue: no one wanted to speak after Kennedy. The Massachusetts Senator was a famed speechmaker and still beloved among party faithful. Manatt finally resolved the dilemma by having Kennedy speak on Sunday, while the other five contenders went on Friday.

As the event approached, the party was on its best behavior. “Suppressing their instinctive urge to fight among themselves,” wrote the Times’ Warren Weaver Jr., “the Democrats are trying hard to present a united front on the issues at their national party conference.”

For once, a united front is what the Democrats got. The speakers focused on attacking President Ronald Reagan and his administration.

House Speaker Tip O’Neill kicked things off by calling the administration “a national disgrace” and dubbing Reagan “the biggest budget buster in history” who was “tearing the social safety net to shreds.”

“We have in the White House,” said Cranston, “a man who seems oblivious to some of our greatest national problems, indifferent to others, and whose approach to those he’s aware of is superficial and simplistic.”

“If this administration talked as much about peace as they do about war,” said Glenn, “they could reduce world tensions instead of their own credibility.”

The issue panels were blessedly free of conflict. The final midterm platform included support for national health insurance (again), increased public-works spending to maintain aging roads and bridges, and a freeze in development of nuclear weapons hedged with a commitment to maintain parity with the Soviets to appease defense hawks. The platform was fairly light on specifics, but no one was inclined to fight about that.

“We don’t want any specific numbers in there, even our own,” said AFL-CIO communications director Murray Seeger. “We don’t want this to turn into a divisive scene.”

With limited argument over issues, the primary drama in Philly was the battle between Mondale and Kennedy, the presumed frontrunners for 1984.

The former Vice President, not known as a great speaker, delivered what the UPI called “by far the most electrifying speech of the opening day.” He lambasted Reagan for creating “two Americas – one where the well-to-do get more and more, and one where the rest of us get less and less.” He charged that the administration was “a government of the wealthy, by the wealthy, and for the wealthy.”

Mondale’s speech was interrupted 27 times by applause. ”The best speech I ever heard him give,” enthused Mississippi Gov. William Winter.

Kennedy, meanwhile, toned down his usual bombast. He dropped his long-held grudge against Carter, praising the former president’s stance on “the vital issue of human rights.” But he also encouraged the party to uphold its progressive tradition. “The last thing this nation needs is two Republican parties,” he said.

Like Mondale, he went hard after Reagan, charging him with plunging the country into recession and increasing unemployment. “Ronald Reagan must love poor people,” he quipped, “because he’s creating so many more of them.”

Kennedy was interrupted by applause 57 times; at the end of his speech, the crowd gave him a four-minute ovation.

“I kind of enjoy midterm conventions,” Kennedy said afterward. “I do better at midterm conventions than conventions where they take the roll.”

The Times’ Adam Clymer concluded that the Democrats left Philadelphia “with two leading choices for their 1984 Presidential nomination” in Kennedy and Mondale,” but with more reasons to be happy with both men than they had come with.”

All in all, the 1982 mini-convention – or “party conference,” as Manatt would have it – was a rousing success. “The Democrats went home today feeling good about themselves,” wrote Clymer, “surer than they were when they came that they are a party with a future.”

Mini-Conventions 86ed in ‘86

After the triumph of the Philadelphia conference, it seemed Democrats would want to continue the tradition. But as it turned out, 1982 was the end of the line.

At the 1984 convention, supporters of Gary Hart and Jesse Jackson pushed for a resolution mandating a midterm gathering in 1986. Mondale’s backers opposed the idea, but initially agreed in order to reduce intra-party friction. At the last minute, however, they struck a deal with the Hart camp to instead say that the party “should” hold a midterm conference. (Jackson and his supporters were left out of the bargain.)

When it came time to plan for the mini-convention in the summer of 1985, new party chair Paul Kirk Jr. moved instead to kill it.

Kirk termed midterm conventions “places for mischief” and argued that they exacerbated party divisions. He dismissed the value of platforming the party’s Presidential contenders, saying that Presidential campaigns were too long as it was. He also claimed that the cost of the gathering would approach $1 million.

“I just think it’s wrong to spend a lot of money on… what becomes an exercise in damage control,” Kirk said.

When the matter came up for debate at a party meeting in June, some party members protested. “I would love to showcase our leaders,” said California committeewoman Alice Travis. “Yes, it is a risk, but we must stand up and say we are alive and well and proud to be Democrats.”

Most members, however, agreed with Kirk. They voted overwhelmingly to scrap the 1986 mini-convention. The Democrats haven’t held one since.

A Noble Idea Poorly Executed

What can we learn from the Dems’ flirtation with midterm conventions? Was Kefauver wrong to recommend them? And should the Republicans go ahead with theirs this year?

If Kefauver had lived to see his idea enacted, he would have pointed out the ways in which the Democrats misapplied his suggestion.

For one thing, two of the three conventions were held after the midterms, instead of before. This defeated one of the key purposes Kefauver saw for these gatherings: setting the party’s position for off-year elections.

More importantly, party leaders actively worked to suppress the free-wheeling, lively debate that Kefauver hoped would occur. This was partially because they didn’t want to allow any additional footholds for the reformers to seize power in the party.

But there was an aspect of these conventions that Kefauver didn’t consider: they are, to a degree, advertisements for the party. As such, Democratic leaders understandably wanted to present a united front, which was difficult while the party was in the throes of a major transition.

A multi-day intramural fight over issues might have led to greater understanding and a thorough discussion of important points, just as Kefauver wanted. But it would also have read to the public as an example of the “Dems in disarray” narrative we know so well. (It’s no coincidence that the most outwardly successful of the mini-conventions was 1982, which was by far the most tightly controlled.)

And what about the Republicans contemplating a 2026 midterm convention? I think Carter’s experience in 1978 is instructive. When you’re the party in power and you’re dealing with an unpopular administration, a midterm convention might just amplify existing fissures within the party.

On the other hand, Trump may be broadly unpopular across the country, but he’s still pretty popular with Republicans. As far as I know, there’s no Ted Kennedy waiting in the wings to deliver a rip-roaring speech that undermines the incumbent. So maybe they can pull it off.

If they do, though, it won’t be the kind of gathering that Kefauver envisioned. Not by a long shot.

Leave a comment