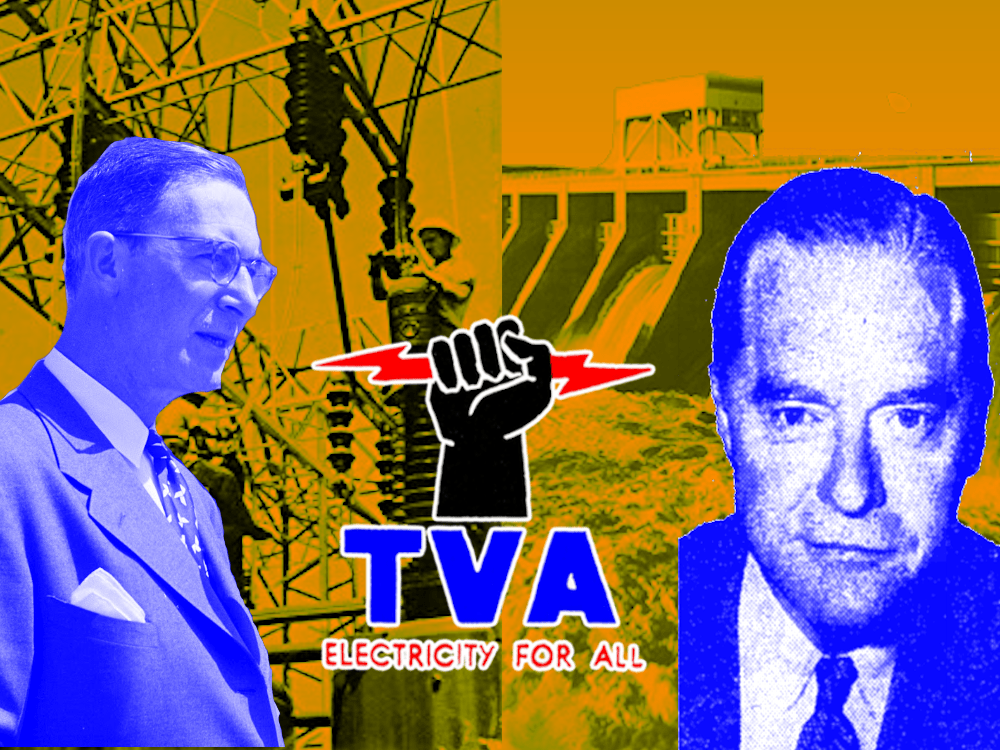

I recently came across a book about the Tennessee Valley Authority, written in 1954 by the outgoing Chairman of its Board of Directors, Gordon Clapp. I probably wouldn’t have picked it up if not for the fact that Kefauver was a champion of the TVA throughout his career. But I’m glad that I did read it.

The book offers a thorough look at the history of the TVA through its first two decades. It also includes an eloquent explanation of the mindset that animated the TVA’s creation, and the New Deal itself. It’s the same mindset that defined Kefauver’s approach to politics. And it’s a mindset that I fear we’re losing in America today, if it isn’t already gone for good.

Expert Witness for the Defense

If anyone was positioned to write authoritatively about the TVA, it was Clapp. He had been with the authority since its foundation in 1933. Starting as associate personnel director, Clapp quickly rose through the ranks to become General Manager by 1939.

In 1946, Harry Truman named him Chairman of the Board, succeeding the legendary David Lilienthal. Upon the appointment, Truman lauded Clapp as “a man of wide experience and understanding of TVA’s problems and opportunities, and one therefore uniquely qualified to provide sound leadership in the future.”

The book was developed from a series of lectures Clapp gave to commemorate the authority’s 20th anniversary. By this time, Clapp’s term as chair had ended; he was not reappointed by new President Dwight Eisenhower.

Ike had attacked the TVA as “creeping socialism” during the campaign, and the agency’s supporters feared that he would dismantle it and turn things over to private interests. (The Dixon-Yates controversy suggested that the supporters were right to worry.)

Perhaps in response to these concerns, Clapp delivered not only a history of TVA, but a defense of the authority and its role. He hoped the book would “help those who want to understand [TVA’s] real meaning, whether they indorse or reject it as good public policy.”

“A Great Adventure in Faith and Works”

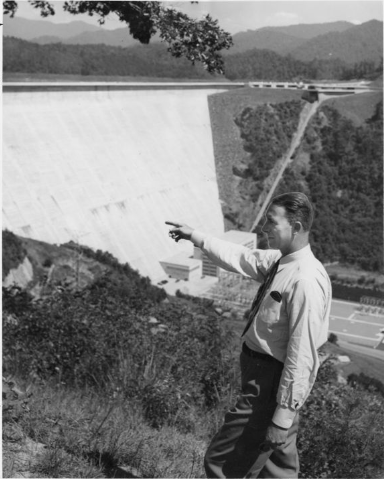

Today, TVA today is primarily a public power utility, but it was originally envisioned as a regional planning agency. In addition to generating power for the residents and businesses in the valley, the authority’s work helped to control and stabilize the river itself.

Prior to TVA, Clapp wrote, “the river ran wild in flood and destruction during the heavy rains of the winter. When the rains stopped falling, the river ebbed to a lazy, powerless stream. Today, the Tennessee River neither destroys nor sinks into idleness.” Instead, the authority’s improvements “put this river to work for man.”

The TVA also put the land around the river to work, improving the soil for farming by growing ground cover to protect the topsoil and producing phosphate fertilizers to make the soil more productive. “With each year of work the people on the land are a little less at odds with the working cycles of nature,” Clapp wrote, and “a little more sure of the future of their families.”

In Clapp’s view, TVA’s success was not just a testament to hard work or good administration – it validated a higher principle: the power of “a faith in ourselves and in more and more of our fellow-men” and “co-operating for a greater public good.”

Clapp believed that this faith, and the ability to work together for the common good, was vital to the flourishing of human civilization. “Faith in one’s self and in others is more than an attitude,” he wrote. “It is a necessary complement to the will to act – to do something or to refrain from doing.”

Clapp believed that humans were only capable of achieving great things if we had that fundamental faith and trust in each other. And he had a point. Undertaking projects that require serious toil and treasure – projects whose full fruition you may not see for years, or even in your lifetime – requires a willingness to work for something bigger than yourself and your own personal fortune.

This is why Clapp described the TVA as a “great adventure in faith and works.” It reflected a major investment of time, labor, and money for the long-term benefit to a region that had long lagged behind the rest of the country. It was an audacious gamble by a country that, even in the throes of the Great Depression, had a fundamental confidence in itself and its ability to do good.

Who could stand opposed to this great act of faith? Clapp believed that opposition was rooted in fear. “We can mobilize every man-hour, every nut and bolt, into a gigantic effort of destruction,” he wrote, “to support our faith in our more limited community when a fear of strangers, ambitious in their insecurity, pervades our lives.”

Where faith in our fellow humans encourages us to come together for the common good, fear encourages us to retreat, to hunker down, to look out for ourselves and our inner circle.

We can see this in the development of American cities. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, fear lead to white flight and to our inner cities becoming hollowed-out and dangerous. In the 21st century, a new generation took a chance on urban life, and many once-declining cities began to flourish again. In the last few years, unfortunately, the pandemic and fear of rising crime rates has led people to retreat and threatened to reverse those hard-earned gains.

Of course, fear was not the only reason that people opposed the TVA. Clapp pointed to the “creeping socialism” accusations as an example of mindless doctrine, that “anything called ‘socialism’ is by that token assumed to be inimical to private enterprise.” In that era, anything that could be associated with Communism was (in the minds of some, at least) automatically un-American and dangerous.

“The neatness of an easy choice between black and white alternatives of doctrine frequently appeals to the uninformed,” Clapp wrote; “it avoids the distracting obligation to reflect about facts and subtleties inherent in most public issues.”

As we’ve seen, even though the Cold War is over (at least for now) and the Red Scare is a long-dead relic, Republicans still don’t hesitate to hurl charges of “socialism” at any Democratic proposal that involves a potential expansion of government, from the Great Society to Obamacare. As Clapp noted acidly, “Doctrine, brittle and neat, is the tool of tender minds in pursuit of a policy that can be embraced without using one’s intellect.”

In response to those critics, Clapp noted that the best argument for TVA’s success was the number of projects, both in the US and around the world, that sought to copy it. During Clapp’s tenure, representatives of countries from Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Middle East came to study TVA and replicate its model back home. And although TVA’s critics stopped America from creating similar authorities in other areas of the country, flood-control projects by the Army Corps of Engineers mirrored some of the TVA’s work.

As Clapp put it, “[T]he water carried from the well of the TVA experience to nourish other river valleys is put in new bottles with different labels to avoid identification of the source.”

How Did We Lose Our Way?

I find Clapp’s words both invigorating and depressing.

They’re invigorating because they make a ringing and eloquent case for big, ambitious projects to make our lives better. But they’re depressing because hardly anyone says things like this today. Sadly, neither the current left nor the right would be inclined toward Clapp’s argument.

Today’s Republicans are obsessed with the idea of “making America great again,” but they seem to have little understanding of what made America great in the first place. Far from preaching faith in our fellow humans, they’re all about fear: fear of immigrants, feminists, city dwellers, and liberals. They view life as a brutal zero-sum game, in which your gain inevitably comes at someone else’s expense.

This isn’t a movement that has room for a concept of the public good. Instead, it’s all about protecting you and yours from a constant assault of hostile outsiders, attempting to take away what’s yours.

The Democrats, meanwhile, do have a concept of the public good. However, they’ve lost the plot on how to achieve it.

Practically every large public works project today is infamous for delays and cost overruns. And that’s not counting the projects that are stopped before they can begin. It seems much harder today to build things than it used to be.

Part of the reason for that is the numerous choke points built into our system, the web of regulations and restrictions that allow people opposed to a given project to delay or kill it. And most of those regulations and restrictions were strongly supported by Democrats. (The Abundance movement has offered some strong critiques on this point.) But it’s also a matter of mindset.

It’s virtually impossible in a modern, developed society to build a large project that doesn’t have a negative impact on somebody. New development creates additional traffic and a loss of trees and green space. Urban gentrification prices out the people who live in existing low-income housing. Solar arrays and wind farms might ruin the view from some people’s houses.

Individually, these concerns all have some merit. But how do we balance these concerns against the broader public good? Too often, our current process privileges the concerns of a handful of people (especially the wealthy and influential) over the common interest. If we only allow projects that don’t upset or inconvenience anyone, we’re never going to build anything.

And it’s not as though these concerns didn’t exist in Clapp’s day. TVA controversially used eminent domain to displace over 125,000 residents in the path of TVA projects.

Was that unfortunate for those residents? Absolutely. But the positive good of those projects for the public outweighed the harm done to the individual residents that were displaced.

We shouldn’t ignore the impact that big projects can have on individuals. But for mostly well-intentioned reasons, we’ve swung too far in the other direction.

I’d add that regulations aren’t the only barrier to supporting projects for the public good. It also requires, as Clapp noted, a faith in our fellow humans and an optimism for the future.

Unfortunately, if there’s one belief that today’s Democrats and Republicans share, it’s that America – and possibly the world – is in bad shape and headed for doom. That outlook is diametrically opposed to the faith that Clapp espoused.

Fortunately, there is hope. Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral campaign, with its bold ambitions and positive tone, inspired Democrats in and outside of New York City. If he can deliver on his campaign rhetoric, it could give the party a more appealing vision for the future.

I’m not imagining some kumbaya moment where we all agree to forsake our differences. Clapp was clear-eyed enough to know that was a pipe dream. Rather, he hoped that we could cooperate toward a shared vision of the greater good.

As he wrote: “The community of faith in men we build around us can stand and survive many divisions among the many things about which we differ if only we can unite in the few things we can do together.”

Amen.

Leave a comment