In the past, I’ve written about Atlantic Union, the concept of the world’s democratic countries forming a federation to counter the rise of authoritarianism around the world. Estes Kefauver was a strong proponent of Atlantic Union, and was one of the leading proponents of the idea during his time in the Senate.

I’d never heard of the idea before I started studying Kefauver’s life and career. I assumed that it had vanished into history, a bygone relic of the Cold War. But I was wrong. There are still a handful of people out there today who believe in Atlantic Union and are working to make it happen.

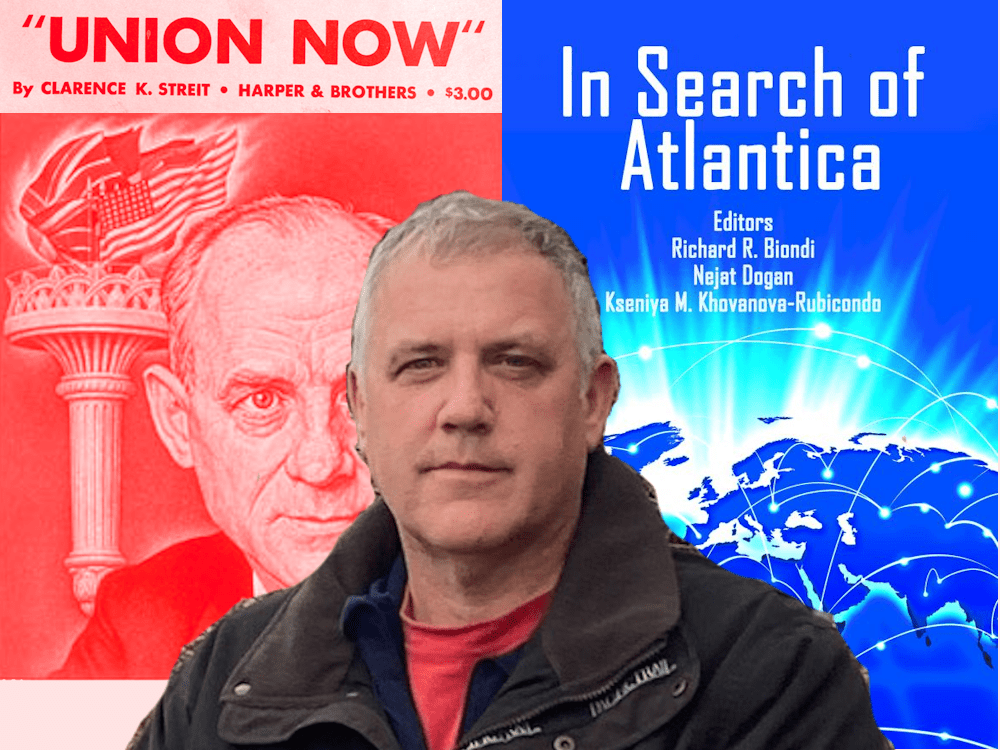

One of them is a man named Rick Biondi, who recently shared with me his project to revive the discussion of Atlantic Union. He believes that a federation of free societies might be the solution for many of the problems that ail America and the world today.

Biondi has spent 25 years studying the history of the Atlantic Union movement and related causes. Through this research, he’s come to believe that “you can’t solve any of [the world’s] problems without solving them at a global level.”

From Skeptic to Believer

Biondi grew up as a “pretty Republican, conservative kind of kid” in the Chicago suburbs. His strong desire to defend his country led him to enlist in the Army, where he served for three years with Ranger and motorized infantry units. He’d hoped to become an officer, but was medically disqualified.

Enrolling in college after his Army hitch, Biondi was seeking a new way to serve and defend America when a fellow veteran gave him a copy of Behold a Pale Horse by William Cooper. Today, Biondi dismisses it as a “total right-wing conspiracy book.” But at the time, he found Cooper’s description of a vast conspiracy led by a secret world government compelling, and he vowed to learn as much about it as he could in order to combat it.

Biondi’s research led him to discover the history of the Atlantic Union and World Federalist movements. This was in the mid-’90s, so he had to look things up the old-fashioned way, poring through back copies of the Congressional Record and obscure magazines on microfilm.

He ran into resistance from his professors at the University of Washington-Seattle, who dismissed his talk of world government as a kooky conspiracy theory and told him it was irrelevant to his chosen major of political science. (He eventually found a couple professors who allowed him to pursue it as an independent study.)

He continued his research as a grad student in international relations at the University of Idaho. By this time, however, he’d warmed up considerably to the idea of Atlantic Union.

Reading the work of Clarence Streit – founder of the Atlantic Union movement – “cured my nationalism in a way,” Biondi explained. He met Dr. Ira Straus, an eminent scholar and longtime advocate of Atlantic integration, who shipped him old copies of Freedom & Union magazine (the official publication of Streit’s Federal Union organization).

Biondi’s connection with Straus led him to the Association to Unite the Democracies, the successor organization to Streit’s Federal Union. He worked directly with the leading advocates of Atlantic integration, including former Rep. Paul Findley of Illinois, who became the primary Congressional champion of Atlantic Union after Kefauver’s death.

Unfortunately, Biondi came to AUD at the worst possible time. After 9/11 and during the run-up to the war in Iraq, anti-European sentiment ran high in America. Biondi said that any talk of forming a federation with Europe typically met with the reaction “Go pound sand, buddy!”

It wasn’t just average Americans who were chilly to the idea. Biondi recalled a 2001 meeting of the Atlantic Council, which was supposed to be about encouraging Russia’s transition to democracy.

Instead, all he heard were neoconservatives spouting Reagan-era “trust but verify”-style slogans. “I thought I was back watching Doctor Strangelove,” Biondi said. He realized that the foreign policy establishment was willing to promote democracy through warfare, but recoiled at the idea of a federal solution.

Biondi left AUD in 2002, but he remained interested in the idea. In 2008, he ran for Congress in Arizona as a Libertarian, hoping to use the race to promote his cause. (Unfortunately, the media largely ignored him, and he received just 3% of the vote.) He wrote a series of magazine articles exploring the possibilities for Atlantic integration in the 2010s.

“Union Now” Anew

Now, he’s created a website to promote the idea. His site proposes that the US appoint a delegation to a second Atlantic Convention to be held by NATO. (The first convention was held in 1962.) The primary goal of the new convention would be to seek an end to the war in Ukraine, but Biondi also hopes the delegates would explore proposals to “secure the future promise of free civilization.”

The first Atlantic Convention was probably the high-water mark to date for the Atlantic Union effort. That convention produced the Declaration of Paris, which were a series of proposals to begin converting NATO into something closer to a federal union.

On July 4th that year, President Kennedy gave a speech in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia that foresaw an Atlantic partnership between the US and a united Europe. Kennedy called for a “Declaration of Interdependence” with Europe, forming a union that would “help to achieve a world of law and free choice, banishing the world of war and coercion.”

“All this will not be completed in a year,” said Kennedy, “but let the world know it is our goal.”

Unfortunately, Kefauver’s death and Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 dealt a huge blow to the Atlantic Union effort, one from which it never fully recovered. Despite this setback, active efforts continued through the ‘60s and ‘70s, spurred on by Rep. Findley and others.

Several factors combined to effectively kill the hopes for Atlantic Union. Biondi cited the Trade Act of 1974, which gave the President “fast-track” authority to negotiate trade agreements subject to a straight yes-or-no vote in Congress, as a key factor. Prior to the act, many multi-national corporations were supportive of Atlantic Union; afterward, they largely abandoned the idea.

Findley pointed to the opposition of “patriotic groups” like the VFW, the American Legion, and the Daughters of the American Revolution. (We’ve certainly seen in past installments that these groups were deeply opposed to anything that resembled world government.) Additionally, the rise of Reagan conservatism drove out many of internationalist liberal Republicans who’d been supportive of Atlantic Union.

If anything, the odds against reviving the Atlantic Union concept have only grown longer since then. The Trump administration has demonstrated a deep hostility toward Europe and toward the concept of alliances in general. Getting this administration on board with Atlantic Union feels like a hopeless cause.

Even Biondi admits that the pursuit of Atlantic Union feels “damn near impossible” in the current climate. “Now, no one even wants to talk about it.”

Despite that, he remains optimistic that its time will come again. He believes that a lot of the thorniest issues we face today can only be solved through a federal approach.

As an example, he noted the affordability crisis and concerns about the outsourcing of manufacturing to low-cost countries to benefit corporate profits. “It’s like Animal Farm,” Biondi said. “Multi-national corporations are more equal than others.”

In an Atlantic Union, there would be genuinely reciprocal trade agreements between nations, rather than one-sided pacts that exploit cheap labor and throw Americans out of work.

(Biondi’s site uses the phrase “Make Atlantica Great Again,” a ploy to appeal to Trump’s base. He’s sympathetic to the issues that animate the MAGA movement, but he believes they’ve embraced the wrong solutions.)

Biondi also mentioned the rise of AI, and the possibility that it may lead to higher unemployment. If the responsibility for defense could be shifted to the Atlantic Union – and if they were able to forsake a large standing army in favor of a smaller, militia-style force – that would free up money to strengthen the social safety net and invest in training to help workers get back on the job market.

The Search for Another Kefauver

That all sounds good. But what will it take to get discussion of Atlantic Union back on the table?

Biondi believes the key is to find an up-and-coming politician who’s willing to be the next Kefauver. He hopes that an aspiring officeholder will read his site and decide to take up the cause, much as Kefauver was introduced to the idea of Atlantic Union by Ed Orgill and Lucius Burch in Memphis during his 1948 Senate campaign.

“I’m looking for someone who’s willing to be a spokesman,” he said. “Can we find somebody who’s willing to talk about a controversial idea?”

Biondi cites the election of Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Zohran Mamdani as evidence that ideas that were off limits in America a decade or two ago are now possible. “If we can find that person” to be the new face of Atlantic Union, “I think we can have a real conversation.”

Biondi’s biggest dream would be to get the world’s richest man on board. His site calls for Elon Musk to host a “Transatlantic Citizens Congress” on X. “I want to turn him into Andrew Carnegie,” Biondi said, citing the steel baron who became a staunch advocate for world peace.

He noted that Musk’s native South Africa was envisioned as a founding member of the Atlantic Union. He also pointed out that if Musk wants to realize his dream of colonizing Mars, he’ll need international cooperation.

“If I can get Musk to change his tune,” Biondi concluded, the prospects for Atlantic Union would take on new life.

For the time being, Rick Biondi is doing his best to keep the Atlantic Union flame alive while seeking a new champion to pick up the torch. The idea may seem like a long shot now, but the same was true when Clarence Streit first proposed it.

And despite the odds, it’s an ideal powerful enough to remain worth pursuing. To quote from President Kennedy’s 1962 speech, Atlantic Union “would serve as a nucleus for the eventual union of all free men–those who are now free and those who are vowing that some day they will be free.” What could be more American that the pursuit of freedom?

(NOTE: This post originally misstated Rick Biondi’s military service. I have corrected it at Rick’s request. I apologize for the error.)

Leave a comment