I’m old enough to remember the end of the Cold War. I remember the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. I remember the euphoria of the time and the hope that world peace might be on the horizon, that moment Francis Fukuyama famously called “the end of history.”

In the years leading up to the Cold War’s end, I remember a distinct softening of the way movies and TV shows portrayed people living behind the Iron Curtain. I call it the “Communists Are People Too!” era. Instead of being portrayed as dupes, fanatics, or villains, citizens in Communist countries were portrayed as being… people like us.

For instance, here’s the Billy Joel song “Leningrad,” which came out in 1987 (shortly after his goodwill concert tour of the Soviet Union):

Or take this GE commercial from 1990, celebrating the opening of the Hungarian economy:

The message was clear: Communists aren’t our enemies anymore. They’re fellow human beings. Perhaps, even, we can be friends – and we can live together in peace.

We had a brief moment like that in the mid-1950s as well.

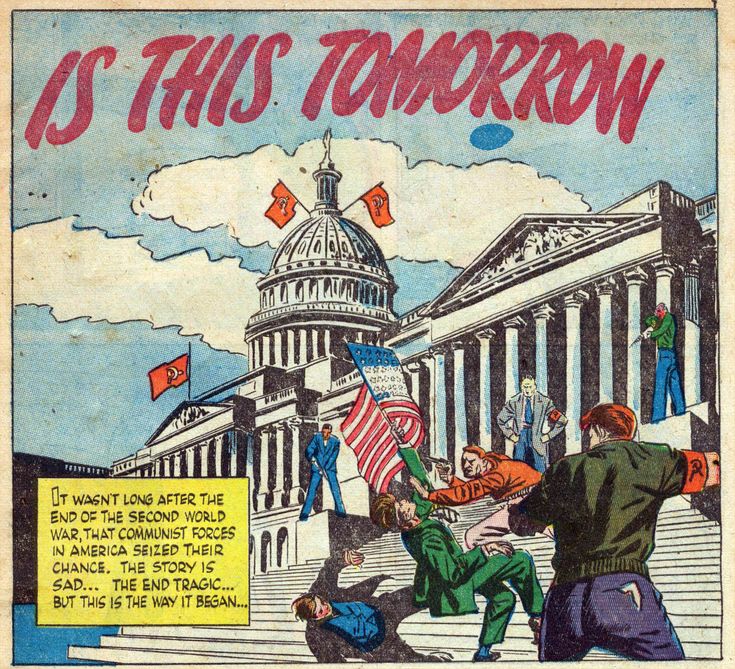

We tend to think of the 1950s as a solid decade of anti-Communist hysteria, but that wasn’t consistently true. Joseph McCarthy’s reign of terror was over after 1954. There was another uptick after the Suez crisis of 1956 and the launch of Sputnik in late 1957.

In the middle of the decade, though, things cooled off a bit. The Geneva Summit in July 1955 between the US, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union raised hopes for a real thaw in the Cold War. World peace suddenly felt like a realistic possibility.

Even during that relatively calmer period, though, there was plenty of latent mistrust toward Communists waiting to be stirred up. A bizarre incident from the 1956 election showed how much anti-Communist sentiment was out there, but also showed how things had cooled since the frenzied heights of the Red Scare.

A Vote for Comrade Kefauver?

The controversy began in May 1956, as the Democratic primary was reaching a decisive stage. After victories in New Hampshire and Minnesota, Estes Kefauver had Adlai Stevenson on the ropes. If Kefauver won back-to-back contests in Florida and California, Stevenson’s hopes for the nomination would likely be finished; on the other hand, losses in both primaries would definitely extinguish Kefauver’s chances.

Into the fray entered Time magazine. Publisher Henry Luce was a huge fan of Dwight Eisenhower and openly hostile to Kefauver. In the May 28th issue – which hit newsstands just before the Florida primary – Time published a bombshell: the Communist Party of the United States supported Kefauver for President.

The item was brief – only a couple paragraphs – but it charged that the Communists had declared that their “main effort will be to change the course of the Democratic Party in an all-out attempt to defeat the ‘Cadillac Cabinet of Eisenhower and Nixon.’” According to the item, the Communists would do this by encouraging a coalition of “labor, the farmers, and the Negro people” to push the Democrats to the left.

Allegedly, the Communists didn’t want Stevenson, whom they criticized for “vacillations and retreats” and supporting the “Johnson-Rayburn line of ‘party unity’ with the Dixiecrats.’ Nor Averell Harriman, whom they accused of allying with Truman in attacking the Geneva Summit. No, they were for Kefauver. According to Time, the Communists praised his campaign as “beneficial in all respects.”

The magazine cited no sources for the item. Given the timing, it seemed calculated to inflict maximal damage on Kefauver’s campaign on the eve of a pivotal primary.

Following Time’s lead, reporters asked Kefauver about the charge during a campaign stop in Tampa.

Kefauver expressed skepticism that the story was legitimate. He noted that Time’s article included no “name, place, or date.” When his campaign inquired about the source of the story, Time said only that it came from a “publicity handout.” Kefauver noted that this supposed endorsement had not appeared in the Daily Worker, the Communist-affiliated newspaper, nor had it run in any other newspaper or wire service.

Regardless, Kefauver unequivocally repudiated any endorsement from the Communist Party. Though he championed civil liberties for Communists and others, he didn’t want their support.

“I do not want any Communist voting for me because I am unalterably opposed to Communism and the things for which it stands,” he said. In case that wasn’t clear enough, he added, “I have not asked for and will not accept any support from any Communist. Any such action would only be for the purpose of damaging me.”

He noted that his record in Congress was strongly anti-Communist. He pointed out that both his campaign manager Jiggs Donahue and senior strategist Howard McGrath had tried several high-profile cases against Communists.

Kefauver’s denials largely shut down the story. But his suspicion, it turns out, was somewhat misplaced. The story was real… but also misleading.

The Rest of the Story

Enterprising wire-service reporters did something that Time hadn’t bothered: they contacted the Communist Party of the USA to ask whether the story was true.

A spokesman confirmed that the Claude Lightfoot, the Party’s Illinois chairman, had prepared a report on the 1956 election. While the spokesman would not confirm or deny the specific quotes in Time’s article, he said the criticisms of Stevenson and Harriman, as well as the Eisenhower administration, were accurate.

The spokesman firmly denied, however, that the Communists had “by direction or indirection” endorsed Kefauver. He added that the Party would take an official position on the election after the conventions.

Lightfoot confirmed authorship of the report, but said he’d recommended that the Party try “influencing policy-wise the course of both parties.” He expected this effort would focus on the Democrats, since their positions were closer to the Communists. However, he did not expect the Party to endorse either major-party nominee.

The Communist Party published Lightfoot’s report in early June, and it was exactly what he and the Party claimed. The report argued that the Communists’ best chance to influence American politics was (as we would say today) to shift the Overton window to the left. The way to do that, Lightfoot claimed, would be to unite the proletariat (workers, farmers, and black people) behind the Democrats.

For this to work, however, the Dixiecrats’ influence within the Democratic Party would need to be reduced. (Thus the criticism of Rayburn and Johnson’s push to hold the Democratic coalition together through strategic alliances with Eisenhower whenever possible.) Lightfoot understood that Stevenson –notoriously indecisive and known for straddling the fence – wouldn’t be the man to lead this crusade.

It was the same strategy that Paul Butler would try to enact after the election with the Democratic Advisory Council: make the Democrats a straightforwardly liberal party. There was nothing wrong or un-American about this idea – but a Communist said it, so that made it scary and suspicious.

And what about the Kefauver part? Here are the full relevant mentions of him:

The Kefauver campaign has helped to sharpen up the issues considerably. His campaign thus far has been beneficial in all directions. It helped to ignite the flaming moods of the farmers; it has proven that a forthright stand on civil rights does not necessarily mean isolation from Southern votes… The Kefauver candidacy furnished the first real proposal emanating from Democrats on the peace issue. It has been a compelling factor in forcing Adlai Stevenson to take a more forthright stand on a whole number of questions.

Lightfoot was praising Kefauver for running a stalwartly liberal populist campaign. By running at Stevenson from the left, he forced the front-runner to commit to actual positions – more liberal ones.

Because Kefauver was popular with farmers and far more effective on farm issues than Stevenson, he might win those voters away from Eisenhower. Similarly, Kefauver’s willingness to take a bolder stand on civil rights than Stevenson might move black voters into the Democratic column.

In summary, Lightfoot believed (correctly) that Kefauver was moving the Democrats to the left. But it wasn’t exactly an endorsement of him, or a statement that Kefauver shared the Communists’ views.

The controversy faded quickly after the Florida primary, and that should have been that. But the GOP couldn’t resist one more kick at the hornet’s nest.

Republicans Take a Swim in the Sewer

In late June, after the primaries but before the conventions, the Republican Senate Policy Committee issued a pamphlet titled “Senate Republican Memorandum.” It alleged that “the official Communist line” was “the Republicans must be defeated and all support thrown to the Democrats.” It cited Lightfoot’s report as its source.

The Committee tried to duck blame with a weaselly disclaimer in small type stating: “Neither the members of the Republican policy committee nor other Republican senators are responsible for the statements contained herein, except such as they are willing to indorse and make their own.” (The committee wasn’t responsible for its own memo?)

Since this charge was aimed at the Democratic Party generally instead of Kefauver specifically, Democrats took extreme offense. And they voiced their displeasure, loudly, on the Senate floor.

Oregon Senator Dick Neuberger blasted the Republicans’ “discredited smear campaign” and asked how the Policy Committee could allow the document to be issued while simultaneously disclaiming responsibility for it.

Hubert Humphrey added his own barrage, saying, “I am fully fed up with this draping of the bloody shirt around the shoulders of Democrats,” noting that Democrats had collaborated with the administration on anti-Communist measures. He attacked the Republicans for claiming to support clean campaign while allowing the “gremlins and goblins in the sub-basement” to play dirty. If Republicans insisted on “the politics of the sewer,” he added, Democrats would have to answer in kind.

Kefauver called on President Eisenhower to denounce the pamphlet. “If Mr. Eisenhower wants to disavow such despicable and dirty politics,” he said, “now is the time for him to do it – not six months from now after the campaigns are over.”

Styles Bridges, chairman of the Republican Policy Committee (and known McCarthy supporter), was conveniently absent during this discussion. (The Committee later called the pamphlet a “staff job” and said they hadn’t approved it.)

But the Republicans present recognized that they’d gone too far – and apologized.

Senator H. Alexander Smith of New Jersey said, “I disagree with it completely; it is shameful. I am overwhelmed with regret. As a member of the Republican party I cannot tolerate this.”

Minority Leader William Knowland also repudiated the pamphlet, adding that Democrats and Republicans were each “as devoted to the interests of the United States as the other.”

It’s a good thing for Republicans that they climbed down from that particular attack, because the following week, Soviet Ambassador Jacob Malik celebrated Eisenhower’s official announcement that he would run for re-election. “I’m for Eisenhower,” said Ambassador Malik. “The people of Europe know him. They like him and trust him. We can do business with President Eisenhower.”

Wisely, the Democrats did not try to argue that Ike was a Soviet dupe.

Postscript: The Cold War Briefly Warms

What can we learn from this incident? To me, it’s a testament to how much the Red Scare mania had relaxed by 1956. If this same story had occurred in 1952, or 1954, it likely would have dominated the campaign. This time, it was a relative blip. Anti-Communist paranoia still existed; Kefauver and the Democrats were outraged at the suggestion that they were the Communists’ choice. But everyone moved on fairly quickly.

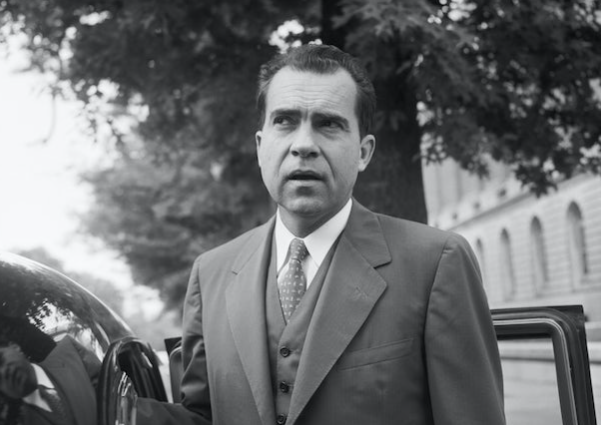

Also, it’s interesting that the Republicans were so quick to disavow the Program Committee pamphlet. I’m sure they were eager to shed the gutter-fighting reputation that McCarthy (and Richard Nixon) had earned them.

But Smith and Knowland’s disavowals reflected a generosity of spirit that they wouldn’t have had a few years earlier. (Maybe they were just relieved that they didn’t have to worry about McCarthy accusing them of being fellow travelers.)

As we know, the hopes for world peace raised by the Geneva Summit proved to be a false dawn; it would be three more decades before the Cold War ended. But it’s heartening that America came close to recognizing – if only for a moment – that Communists are people, too.

Leave a comment