One of the great hypotheticals about Estes Kefauver is: What if he had lived through the 1960s?

Kefauver died in August 10, 1963, two weeks before the March on Washington. He did not live to see the great flowering of the civil rights movement. Nor did he see the turbulence later in the decade: urban riots, campus protests, the Summer of Love, Woodstock, the assassinations of the Kennedy brothers and Martin Luther King, or the national debate over the Vietnam War.

How would he have reacted to the national tumult and trauma of those years? Would he have identified with the protesters and shifted further to the left, or would he – like many people in their later years – have become more conservative?

There’s some evidence in both directions. Kefauver always had an abiding respect and appreciation for dissent and young people, so it’s likely that he would have sympathized with the students and activists calling for change. On the other hand, he was also a deep believer in working within the system, so it’s quite possible that he wouldn’t have considered protests – especially those involving riots or occupation of campus buildings – as the right way to bring about that change.

While it’s impossible to know for sure, there’s another data point: in 1968, during the height of the storm, several of Kefauver’s children endorsed the insurgent Presidential campaign of Minnesota Senator Eugene McCarthy – and claimed that their father would have done the same.

McCarthy’s campaign bore some resemblance to Kefauver’s first try for the Oval Office in 1952. Like Kefauver, McCarthy challenged a sitting President (Lyndon Johnson, in his case) in the New Hampshire primary, calling for withdrawal from Vietnam.

Initially, McCarthy’s bid was viewed as a quixotic long shot – but after almost defeating LBJ in the Granite State, the Minnesotan suddenly seemed a viable challenger. And as in 1952, the incumbent President abandoned his re-election bid not long afterward.

Like Kefauver’s 1952 event, McCarthy’s campaign was enthusiastically supported by young voters. In another similarity, the campaign inspired a song (in this case, by legendary folk group Peter, Paul, and Mary).

Unfortunately for McCarthy, the parallels to Kefauver didn’t end there. He struggled to raise money, and since the party establishment was against him, he had a hard time converting his popular support into delegate strength. And like Kefauver, his toughest opponent didn’t even enter the primaries.

In 1968, the Adlai Stevenson role was played by Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who entered the race after LBJ dropped out. Unlike Stevenson, Humphrey wasn’t a reluctant candidate. However, he skipped the primaries, instead relying on party leaders to line up his delegates.

In Tennessee, there was no primary. Instead, the party held its state convention on June 28 and committed all 51 delegates to Governor Buford Ellington as a “favorite son” candidate. The governor was a close political ally of LBJ, and the move essentially sewed up the Tennessee delegation for Humphrey. (The unit rule bound all the state’s delegates to support the same candidate.)

This move – and especially the heavy-handed way the convention was run – angered McCarthy’s Tennessee supporters (admittedly, a relatively small group). They convinced their candidate to make a visit to Nashville in mid-July, so that they could make their displeasure public. (It’s a sign of McCarthy’s erratic political instincts that he made his first campaign visit to the Volunteer State after the delegates were pledged, and too late to do him any good.)

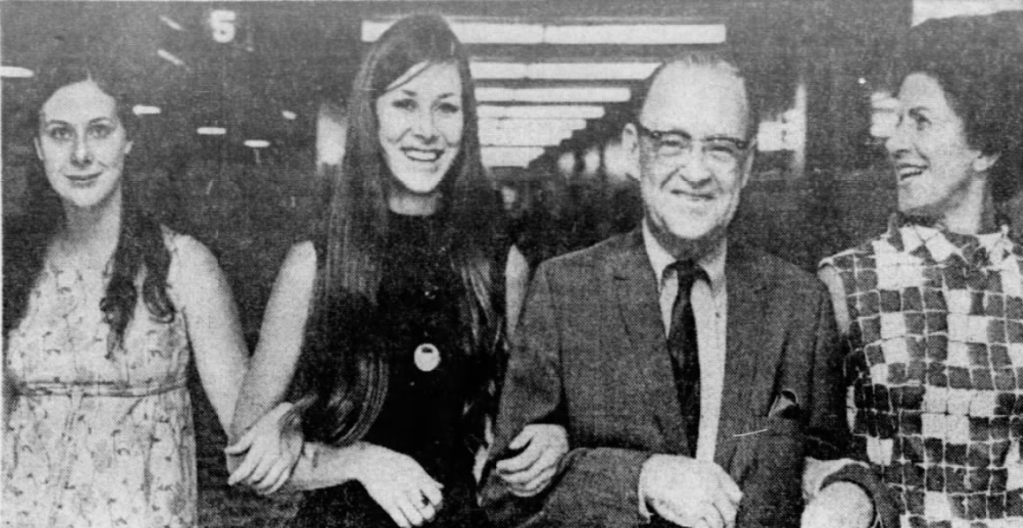

McCarthy arrived in Nashville on a broiling 90-degree day, but that didn’t stop a crowd of 400 people from coming out to greet him at the airport. Chief among them was 20-year-old Diane Kefauver, Estes’ second-youngest child. She handed McCarthy a coonskin cap, a treasured relic of her father’s campaign.

The Senator held an event at Vanderbilt University. Before he spoke, Diane told the crowd why she supported McCarthy for President.

“Senator McCarthy is the man for our generation – because he is the man who cares for our generation,” she said. “He has caught the ideals, the hopes and dreams of our generation.”

Because of this, she said, “we labor for him on the campaign trail in spite of the Tennessee delegates,” and she promised to “carry the fight on to Chicago where we’ll win for him the nomination in August, and the presidency of the United States in November.”

It was Diane’s first time giving a campaign speech. She admitted that she’d been nervous, but she’d felt the need to come through – both for the sake of McCarthy, and for that of her late father.

She implied that if Estes Kefauver were still around, he would also have backed McCarthy, because he “would have embraced the ideals and the hopes for America on which America’s future so greatly depends.”

(Diane Kefauver was joined at Vanderbilt that day by another politician’s child: Senator and Vice President Albert Gore, Jr., who also spoke in favor of McCarthy.)

Diane was not alone among the Kefauver children in backing McCarthy. She and her younger sister Gail appeared at a pro-McCarthy rally before the Tennessee convention in June, and they both went to Chicago in August, although they could not secure guest passes to the convention and wound up watching it from their hotel. Their older sister Lynda was also known to support McCarthy.

In the end, as we know, McCarthy’s 1968 campaign met the same fate as Kefauver’s did in 1952. Humphrey – the candidate of the party leaders – rolled to the nomination on the first ballot.

Unlike Kefauver, McCarthy did not immediately endorse the nominee, nor work on Humphrey’s behalf during the general-election campaign. It wasn’t until the week before the election that McCarthy confirmed that he would vote for Humphrey. And just as in 1952, the Republican candidate – in this case, Richard Nixon – emerged victorious.

So, to return to the original question: Would Kefauver, if he had lived, have backed McCarthy for President in 1968? His children clearly thought so. His former Tennessee Senate colleague, Albert Gore, Sr., did not formally endorse McCarthy but pushed hard for a peace plank in the Democratic platform, making an eloquent anti-war speech at the convention.

Given all that, I think there’s a good chance that Kefauver would have been in McCarthy’s camp.

However, I would definitely not say that McCarthy was the political heir to Kefauver. They both mounted insurgent campaigns against a party-backed favorite, but their differences far outweigh the similarities.

McCarthy was running in support of an issue – opposition to the war. It’s not clear how much he even wanted to be President. Kefauver, meanwhile, was running in his own right, and he wanted the office badly. McCarthy’s campaign style – full of quips and snark – was diametrically opposed to Kefauver’s homey sincerity.

And their political bases were quite different. McCarthy attracted the high-brow collegiate intellectuals who frequently looked down on Kefauver, while the working-class and rural folks who’d supported Kefauver tended to back Robert Kennedy, until his tragic assassination.

Also, to the degree that Kefauver got in his own way in chasing the 1952 nomination, it was because of his unwillingness to compromise his principles to win delegates. To the degree that McCarthy got in his own way in 1968, it was because of his self-destructive streak and his bitterness and spite toward the Kennedy family.

In short, to paraphrase Lloyd Bentsen: Gene McCarthy, you were no Estes Kefauver.

Leave a comment