The Democratic Party of the 1950s was in transition. The old party – an agglomeration of Southern conservatives, urban bosses, and working-class ethnics – was dying, but not yet dead. The new party – multi-racial, better-educated, uniformly liberal – was emerging, but wasn’t yet born.

Those seeking to lead the Democrats in that decade – from Harry Truman to Adlai Stevenson to Lyndon Johnson to Estes Kefauver – had to try to add new voters without losing old ones, and find ways to placate groups whose views were diametrically opposed to one another. It was nearly impossible, and all the aforementioned leaders struggled to varying degrees.

One other leader from this era – far less remembered today – was Paul Butler, who served as chairman of the Democratic National Committee from 1954 to 1960. During his stormy tenure, Butler’s primary contribution was creating the Democratic Advisory Council, which overlapped with Dwight Eisenhower’s second term.

The DAC was… well, it’s hard to sum up. Like the party itself, it was full of contrasts. It included some of the most prominent Democrats – yet it was publicly disowned by the party’s two most powerful leaders. It simultaneously offered a bold new voice for the party, while also driving a wedge into its existing divisions. It garnered headlines and punchlines in equal measure. It was both a crashing failure and an underrated success.

Confused? Yeah, the DAC was like that. Let’s see if we can make some sense of it all.

Liberals Feeling Left Out

Recently, we’ve considered the Democratic transition from the position of Southern conservatives. From the Civil War until the New Deal, they had dominated the party, and they’d had considerable sway in deciding Democratic policies and the candidates nominated to national office.

After the New Deal, however, Southerners lost control of the national party. Worse, the upstarts elbowing them aside sought to recruit new groups – like blacks and labor unions – who were anathema to the old South. It was no wonder they kept threatening to form a third party to ensure that their interests received attention.

Now, let’s consider the perspective of those younger liberals. They’d joined the party out of excitement over Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal, and hoped to build on FDR’s accomplishments. Instead, they encountered a sclerotic conservative Congress seemingly more interested in thwarting the executive branch than in passing new legislation.

The seniority system ensured that committee chairmanships were dominated by Southern conservatives, who blocked all the liberal ideas they could. And leadership was more interested in keeping the crabby old Southerners happy than in fostering the new, young liberal energy in the party.

When the Democrats controlled the White House, things were okay. But when Republicans were in power, life as a liberal was an exercise in frustration.

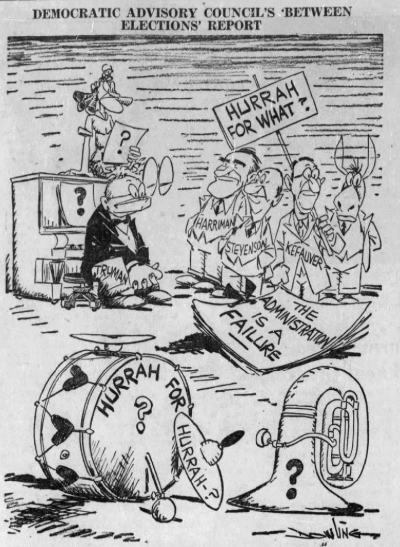

Enter Butler. He saw the problem plaguing Democrats ever since Ike’s election: who would speak for the party? Kefauver had tried to claim that role, as had Stevenson, but neither had really succeeded.

The perceived lack of leadership contributed mightily to the Stevenson-Kefauver ticket’s landslide loss in 1956. “The election of 1956 was over before the campaign began,” moaned New York Senator Herbert Lehman, adding that “almost everything the [Congressional] leadership did during that time was designed to prevent any controversial issue from being seriously joined or vigorously debated.”

The DAC was Butler’s answer. The council included about two dozen of the party’s most prominent leaders – including Stevenson, Kefauver, Lehman, Truman, Eleanor Roosevelt, and others – who would issue formal statements on events of the day, criticizing the Eisenhower administration and laying out a policy vision for the next Democratic administration.

The council had a top-notch staff. Charles Tyroler II, who managed Kefauver’s 1956 vice-presidential campaign, was named executive director. Longtime Kefauver assistant and speechwriter Dick Wallace also served on staff, as did former Secretary of State Dean Acheson, historian and scholar Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and eminent Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith. A veritable Murderer’s Row of Democratic talent!

There was just one problem – well, two problems. First, the DAC was designed to be a majority-liberal body. Butler wanted to push the party to the left, and hoped the DAC could counter the influence of conservative Southerners and urban bosses.

This meant that conservatives – especially Southerners– were wary of the DAC from the start. Camille Gravel, a DAC member from Louisiana, warned that “we might be playing with political dynamite” if the council tried to tell Congressional leaders what to do, and predicted “trouble with our states in the South.”

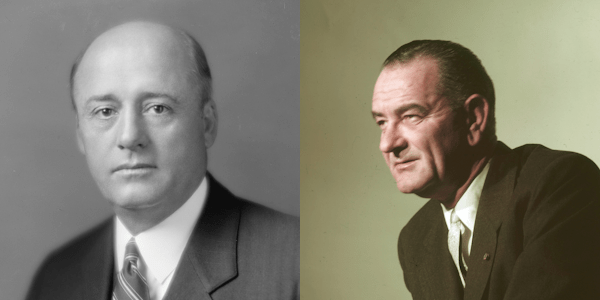

The second problem was larger, and potentially fatal. The two most powerful Democratic politicians at the time were Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, and neither wanted any part of the DAC.

Rayburn and Johnson considered themselves the leaders of the party, and they weren’t interested in advice on how to do their business, especially from a bunch of liberals.

This wasn’t just ego talking. The two Texans had to work with a caucus that spanned the ideological gamut from the most liberal members to the most conservative. They also had to deal with Eisenhower’s massive popularity, including in many of the states their members represented.

As a result, their strategy was to cooperate with Ike as much as possible, spotlighting issues that united pro-administration Republicans with Democrats wherever they could. In essence, exactly the opposite of what the DAC was trying to accomplish.

Shortly after Butler rolled out the DAC concept, Johnson wrote to Rayburn thatit was “capable of deepening divisions within the Democratic Party,” adding that Republicans wouldn’t vote for legislation proposed by “a committee whose sole objective is to… elect a Democratic Congress in 1958 and a Democratic President in 1960.”

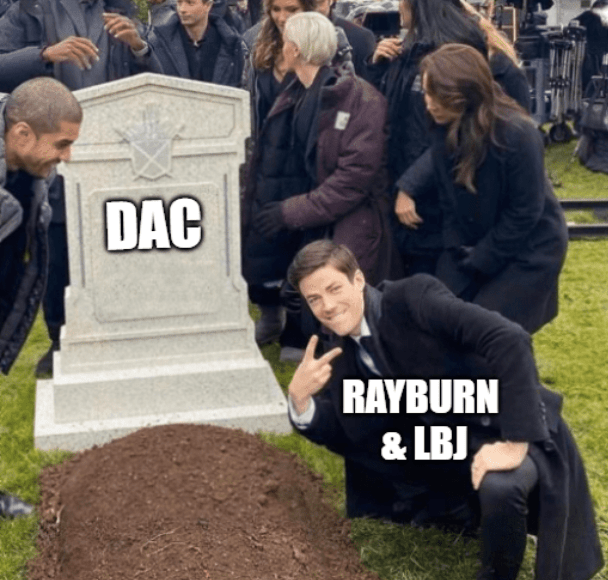

As a result, both Rayburn and Johnson publicly – and loudly – declined to join the DAC. Their rejection led most congressional Democrats, as well as several Southern governors, to also refuse membership. The only two exceptions were Kefauver and Hubert Humphrey. Their participation only highlighted the DAC’s liberal slant.

Rayburn and Johnson probably thought that they’d succeeded in killing in the DAC in the cradle. But they didn’t know Paul Butler.

Ready or Not, Here We Come

Somewhat unusually for his era, Butler believed that political parties should be organized around issues, rather than coalitions and personalities. He once said that the worst failure of the American political system was its “total lack of disciplinary authority in implementing the provisions of the party platform.”

Also, Butler was more into ideas than people. He considered the DAC the way to make Democrats a more cohesive, ideologically liberal party. He wasn’t going to let a minor thing like the vast majority of the party’s elected leaders taking a walk stop him from executing his grand vision.

Over the next four years, the DAC issued a total of 61 statements, covering issues from economic policy to natural resource management to foreign affairs and more. And despite the best efforts of Rayburn and Johnson, the press frequently treated these statements as official Democratic positions.

“The US political system has been often criticized for its failure to produce a coherent and challenging opposition between national elections,” wrote the Dayton Daily News in a November 1957 editorial. “For that reason, the Democratic hierarchy rates an ‘A’ for effort for taking up the chore of periodic policy review.”

The DAC zeroed in on the most controversial issue in the party: civil rights. In response to the 1957 crisis over the integration of Little Rock Central High, the DAC called on Democrats to support the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, and to enforce other civil rights legislation currently on the books.

Political columnist Gould Lincoln praised the DAC for “throw[ing] down the gauntlet on the civil rights issue.” He predicted that “Southerners may expect the presidential candidate in 1960 firmly committed to the enforcement of civil rights. They may expect, too, a party platform which spells out this position.”

Johnson and Rayburn, however, weren’t so pleased. They were trying to walk a careful tightrope on civil rights in Congress, and the DAC was threatening to cut the rope out from under their feet.

The 1958 midterms were very good for the Democrats. They added 15 seats in the Senate and 49 in the House, and most of the new members were staunch liberals. The DAC responded by issuing a bold new agenda, entitled “The Democratic Task in the Next Two Years.”

The agenda included increasing federal aid to education, building more public housing, expanding Social Security, raising the minimum wage, forbidding anti-union state “right to work” laws, and increasing foreign aid and defense spending. On civil rights, it called for bills enforcing desegregation and voting rights laws, preventing public schools from closing to avoid integration, and abolishing the filibuster.

The agenda thrilled the liberal New Republic, which called it “electrifying” and praised the DAC for “helping to create a new, liberal national image of the party.”

Not everyone was fully on board. Kefauver told the Knoxville News-Sentinel that he supported most of the DAC’s agenda. However, he suggested that the call to reopen closed schools and ban right-to-work laws weren’t within the federal government’s power, and he opposed eliminating the filibuster, calling it “an aid to deliberation.”

Johnson and Rayburn were far less interested. “The biggest weakness in what the Democratic Advisory Council recommends is that the two most powerful Democrats in Congress… are not members of the council,” noted the AP. “By standing aloof they can pick and choose what they want to push or fight for.”

Predictably, they ignored most of the DAC’s agenda. By the end of the 1958 session, they’d passed less than a third of it. They didn’t see value in antagonizing conservatives in their caucus for the sake of bills that Eisenhower would surely veto.

In response, the DAC issued another statement criticizing Rayburn’s and Johnson’s attempts “to water-down proposals to the limits of what the president might accept… The American people are entitled to have the lines definitely drawn.”

Preparing for Electoral Battle

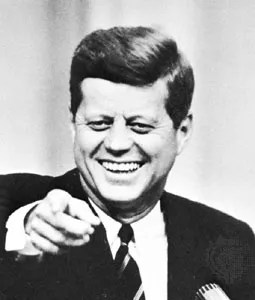

As the 1960 election approached, several members of Congress who had previously spurned the DAC – but now sought the Presidential nomination – agreed to join, including John F. Kennedy and Missouri Sen. Stuart Symington. (Notably still absent: Lyndon Johnson, who maintained his boycott.) Also, the council tried to connect with the South by adding Florida Gov. LeRoy Collins, a known moderate.

In December 1959, the DAC issued a 10,000-word, 22-point manifesto laying out a program for 1960. Like the previous year’s agenda, it presented an expansive program of liberal governance.

The manifesto called for a national health-insurance program. It recommended aggressive slum clearance and urban renewal, a doubling of annual housing construction, and the construction of housing for the elderly. As with the midterm agenda, it called for a significant increase in federal funding to states for education and more. It called for the creation of a national peace agency, reporting directly to the President, to provide “dramatic proof to the world that the United States is sincere in its desire for peace and disarmament.”

Just like the midterm agenda, the manifesto called for the Democrats to take a firm stand in favor of civil rights. In addition to enforcement of existing civil rights laws, the manifesto called for Congress to formally denounce opposition to school integration as a violation of the Constitution. It also called for new laws to protect voting rights as well as the physical safety of people held in federal or state custody.

This move on civil rights threatened to splinter the DAC entirely. Several Southern members of the council dissented from this portion. Other Southern members who generally supported civil rights – like Collins, Kefauver, and Camille Gravel – worried that the agenda was too broad and unrealistic.

The civil-rights positions weren’t the only controversial parts of the agenda. Critics claimed the agenda was unaffordable and would hike inflation. Columnist George Sokolsky argued, “If all the schemes in [the agenda] were to be implemented, the cost of government would be so great and the load on the taxpayers so heavy that this country would be broke.” (Lyndon Johnson agreed, dismissing the DAC’s agenda as “pie in the sky.”)

Others, like the AP’s James Marlow, were impressed by the ambition – Marlow called the agenda “a rocket shot at the election moon of 1960” – but wondered why the Democrats hadn’t tried to implement any of it with their huge congressional majorities in the last two years, instead of acting “like sheep under the guidance of Eisenhower.” (The answer, of course, is that Rayburn and Johnson wanted it that way.)

The DAC had drawn clear battle lines for the November election. Would the strategy pay off?

Kennedy Offers A New Dawn… But Says Good Night to the DAC

In theory, Kennedy’s victory in the 1960 election should have been a boon to the DAC. After all, he was a member in good standing. In fact, however, JFK’s win led to the council’s demise.

Kennedy always had an ambivalent relationship with the DAC. In a March 1958 speech to the Gridiron Club, he quipped, “The Democratic Advisory Council has succeeded in splitting our Party right down the middle – and that gives us more unity than we’ve had in 20 years.”

During JFK’s run for the Presidency, he simultaneously courted the DAC while keeping it at arm’s length. He generally supported the council’s positions, even when they were controversial. On the other hand, he understood the need to appeal to the South, and he selected Johnson – who had denounced the DAC from the beginning – as his VP. In typical Kennedy fashion, he managed to charm the party’s various factions without fully embracing any of them.

Once he was President, the stated reason for the DAC’s existence – to provide a voice for the party when it was out of the White House – no longer applied. Kennedy was now the voice of the Democrats, and he didn’t want a bunch of party elders telling him what to do.

Kennedy picked Connecticut machine boss John Bailey, instead of another liberal reformer, to succeed Butler as DNC chair. And as soon as he had a chance, he disbanded the DAC.

However, Kennedy did pursue a liberal course while in office. And after JFK’s assassination, Johnson – the supposed conservative stalwart – enacted an agenda that the DAC would have loved.

Postscript: A Mixed Success in Strange Times

So, the key question: was the DAC a success or a failure? On one hand, the council’s vision of a consistently liberal party did prevail, and they offered an important voice for liberals during their time in the wilderness. On the other hand, the actions of Kennedy and Johnson arguably did more to move the Democrats left than anything the DAC tried to do.

Perhaps the best assessment of the DAC’s influence came from New York Times reporter Allen Drury, who wrote about the struggle between the council and Democratic congressional leaders in February 1958.

Drury proclaimed the DAC “perhaps as good an answer as any to this difficult problem of the party out of executive power.” He noted that “the news business functions in such a way that any organized party group is assured of the widest possible dissemination of its views.” This meant that the DAC’s statements were treated seriously, even if they weren’t official party policy and even if Rayburn and Johnson charted a very different course in Congress.

Drury pointed out that this was actually a pretty effective way for the party to operate. “In a sense,” he wrote, “it permits the Democratic leaders in Congress… to sing sweet harmony with the Administration on Capitol Hill while the Democratic leaders downtown indulge in give-‘em-hell rock-‘n’-roll.”

If Rayburn and Johnson tried to conduct themselves as the liberals that the DAC wanted them to be, they would have antagonized the senior and most powerful members of their caucus, while probably getting a lot less accomplished.

If the DAC and the Rayburn-Johnson faction had agreed behind the scenes to pursue this two-track strategy, it would have been quite clever indeed. But the hostility was real; it was a genuine struggle for power and supremacy within the party.

And that’s why the DAC was never more than a Band-Aid. The factions within the party couldn’t co-exist forever. They had to battle it out, and one side had to win. The DAC was an arrangement of necessity; it wouldn’t have lasted long regardless.

Is it ultimately a good thing for the country that we wound up with strictly partisan liberal and conservative parties? That’s a harder one to answer, and this post is already long enough, so we’ll wrestle with that another time.

Leave a comment