Imagine that you’re running for President. It’s late October, and you’ve spent months traveling around the country trying to win votes. But you’re up against a hugely popular incumbent, and it’s dawned on you that you’re almost certainly going to lose. There’s a good chance that you’re going to get slaughtered. What now?

If you’re the Democratic Party in 1956, you call up your show business friends and stage a coast-to-coast spectacular on closed-circuit television for party leaders and big-deal donors. In defiance of all observable reality, you title the production “Seventeen Days to Victory.”

If it sounds like the band on the Titanic continuing to play while the ship was sinking, that’s a fair analogy. But for one night, at least, the party could forget the coming landslide and enjoy the festivities.

Let’s Put on a Show

The show’s goal was to raise funds for the campaign and whip up enthusiasm among the Democratic faithful as the campaign entered the home stretch. It would be broadcast at fundraising dinners in cities around the country. Dinner prices ranged from as low as $5 a plate up to $100 in DC, New York, and Los Angeles. (In Miami, they let people in for free.)

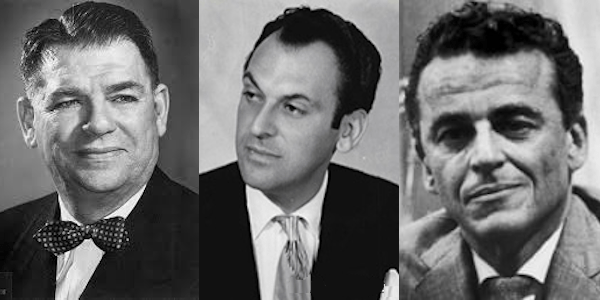

It was a star-studded affair. The script was written by a trio of Broadway luminaries (Oscar Hammerstein II, Moss Hart, and Alan Lerner), along with novelist Herman Wouk. The cast included stars like Henry Fonda, Frank Sinatra, Bette Davis, Leonard Bernstein, Marlon Brando, and Harry Belafonte. Orson Welles was to serve as the master of ceremonies.

Along with the celebrities, the show would include speeches from Adlai Stevenson, Estes Kefauver, former President Harry Truman, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and John F. Kennedy.

It was a technically challenging production. It would originate from five different cities, since the politicians were fanned out across the country campaigning. Stevenson was in Chicago, Kefauver was in LA, Truman was in Washington, Mrs. Roosevelt was in New York, and Kennedy was in Indianapolis. They’d have to find a way to switch seamlessly between sites without disrupting the broadcast.

In the days leading up to the event, there were signs of serious trouble. The closed-circuit TV provider, Theatre Network Television, pulled out just 48 hours before showtime. The provider claimed that the Democratic Party was delinquent in making payments; the party countered that the provider wasn’t able to meet the requirements of the broadcast. (They found another provider.)

Also, Welles had to be replaced as emcee at the last minute. It’s not clear whether Welles’ love of drinking, alleged Communist ties, or general unreliability was behind the last -minute switch. Hal March, host of The $64,000 Question game show, did the honors instead. (Welles still appeared on the broadcast.)

Given the warning signs, Democratic leaders could be forgiven for fearing the big night would be a disaster. But it was too late to call things off. All they could do was sit back, cross their fingers, and hope for the best.

Iiiiit’s Showtime!

And in the end… things turned out pretty well! The broadcast went out successfully to between 30 and 40 cities around the country. (Virtually every media outlet published a different number.)

There were a couple minor hiccups. On one occasion, the TV accidentally displayed the video of a Kefauver speech from earlier in the day while Stevenson was talking. And at the Statler Hotel in Washington, the broadcast was apparently badly distorted, due to a screen that columnist George Dixon said “was wrinkled and bunched like a bed made by a teen-ager late for a date.” According to Dixon, when Kefauver smiled on the broadcast, “he looked like a tickled moose” on the wrinkled screen.

Those glitches aside, the production was a success. Naturally, the evening was full of jabs at Republicans. In one sketch, a comedian pretended to be a member of the Republican National Committee, “explaining” the party’s platform in fast, nonsensical double-talk. In another, two young women sang a parody song entitled, “How you gonna keep ‘em down on the farm once they’ve seen the GOP?”

On the more highbrow side, Carl Sandburg recited one of his own poems, and Belafonte sang a ballad honoring the Democrats’ patron saint, Franklin Roosevelt.

The highlight of the program, however, was the speeches. Kefauver addressed one of his favorite topics, the Eisenhower administration’s broken promises to American farmers. (It might seem odd to have Kefauver give a farm speech in LA, surrounded by Hollywood actors and actresses. However, according to correspondent Clark Mollenhoff, the party decided that “it would be a good idea to indoctrinate these city folks on the seriousness of farm problems.”)

Truman, who proclaimed himself the Democrats’ “number one precinct captain,” did a funny bit of prop comedy featuring a pair of “I LIKE IKE” sunglasses, which the GOP was giving out at campaign stops.

Truman claimed that the glasses were the reason that the administration couldn’t see the country’s many problems. “The glass in them in tinted,” he said, “and when you put them on everything looks rosy and serene.”

The ex-President put the glasses on, and said that when he wore them, all the farmers were happy, shouting “We love low farm prices!” and “Three cheers for Ezra Benson!”

Through the glasses, he looked at cities and, instead of seeing slums, he saw “luxury apartments and five-bedroom ranch houses.” He offered similar “looks” at small businesses (thriving instead of going bankrupt), schools (“I could hardly see any overcrowded firetraps at all”), and working people (“I couldn’t see a single one of my old friends from the labor movement. Through these glasses, all I could see were a lot of monsters called ‘labor bosses’”).

Truman threw in a few pokes at administration officials, saying that the glasses hid the corruption of Attorney General Herbert Brownell and Air Force Secretary Harold Talbott, and made it “so that you can believe that John Foster Dulles is a good Secretary of State.”

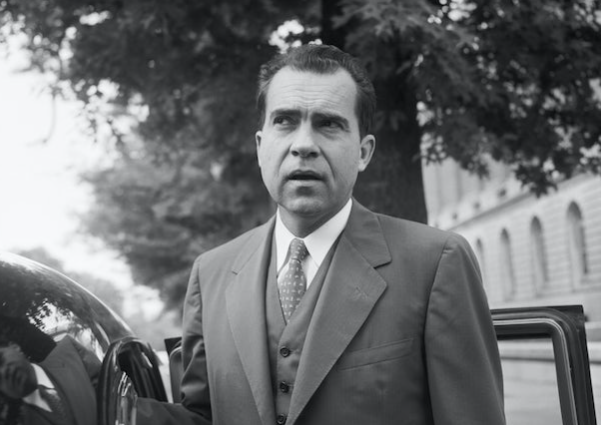

“Just put them on and look at Dick Nixon,” Truman said. “You will be amazed! He looks as clean as a hound’s tooth and every inch a statesman. He has little Lord Fauntleroy clothes and wears a halo.”

Truman concluded by vowing “to take these glasses off and never to use them again. I decided that they were dangerous.”

Stevenson spoke last, delivering a typically lofty speech. He promised that his administration “will release the generous, creative energies of our nation in full flood” and would provide Americans “a relief from fear, a relief from militarism, together with a restored confidence and faith in the future.”

Mocking the Red Scare and our belligerent foreign policy, he said that under Republican rule, “we have been afraid looking under the bed at home and building barbed wire fences abroad, and we have nearly lost our souls in the process.”

Stevenson accused the Eisenhower administration of “encouraging a comfortable complacency toward things as they are – and a suffocating satisfaction with our material well-being.” He added that “the American idea is not of a nation in which every citizen is just a stockholder in some huge corporation. Rather, it is a nation in which everyone owns stock in America, yes, and in himself.”

He encouraged the campaign workers: “I know you will pour into the 17 days that remain of this campaign all the energy and heart you possess.”

Too Much, Too Late… or a Glimpse of the Future?

All in all, the event accomplished its goals. An estimated 75,000 people watched across America, and the Democrats took in plenty of cash for the campaign stretch run.

Although the White House was widely understood to be out of reach by that point, the Democrats still had to defend their majorities in Congress. In the end, they gained two seats in the House and maintained their slim two-seat margin in the Senate.

The event was also a successful display of party unity. There was a potentially awkward situation in DC, where Nancy Kefauver was seated right next to Truman, who had gone out of his way to thwart her husband’s Presidential ambitions four years earlier.

But they both handled the situation with grace. George Dixon praised Nancy for keeping a straight face while listening to Truman heap praise on Kefauver in his speech. “[M]aybe she is a secret practitioner of the mystic art of the east,” Dixon wrote, “and her aural spirit was really sitting on the banks of the Ganges as she seemingly sat there looking into space.”

That said, it’s fair to wonder whether, at that stage of the campaign, it was a wise idea to spend an estimated $100,000 on a televised Hollywood extravaganza exclusively for the benefit of committed Democrats.

Mollenhoff quoted a couple anonymous California Democrats who wondered the same thing.

“We were not selling anything to anyone but ourselves,” noted one.

“If we aren’t sold on the Democrats by now,” remarked another, “the closed-circuit rally won’t do any good.”

Regarding of the wisdom of the event, it was another example of the way that technology was revolutionizing the campaign. The idea of getting Democrats together around the country to connect on a live TV broadcast would have been unthinkable even four years earlier. Television and jet airplanes were combining to nationalize campaigns in a way that hadn’t existed previously.

“Seventeen Days to Victory” may not have produced the promised outcome, but it was a sign of campaigns yet to come.

Leave a comment