Estes Kefauver’s campaigns for President were uphill climbs for a number of reasons. He was perpetually short of cash and staff, running himself ragged on the campaign trail to make up for the resources he lacked. Most of the party’s power brokers hated him and went out of their way to thwart his ambitions.

The challenges he faced were so well-known that he eventually adopted the campaign slogan “Everyone’s against Estes Kefauver except the people.”

However, Kefauver had one powerful ally in his corner: arguably the most famous and influential political columnist of his era. In an era when the line between political commentators and the leaders they covered was blurrier than it is now, this man was practically a member of Kefauver’s campaign staff. He arguably did more than anyone besides Kefauver himself to elevate the Tennessean to the White House. And like Kefauver, he is mostly forgotten today.

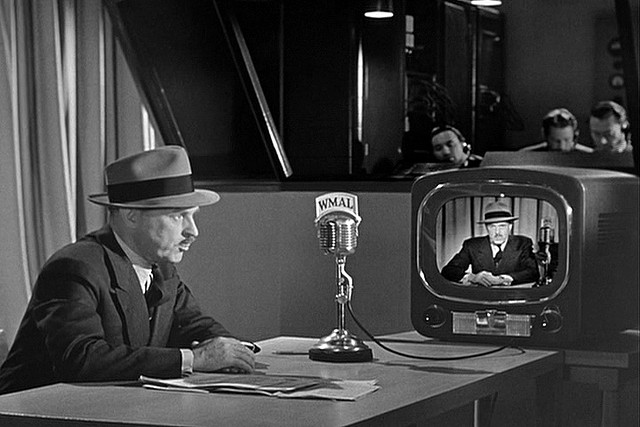

His name was Drew Pearson. If you really want to understand mid-century American politics, you need to know his story.

Why was Pearson so important? Why was he such a strong Kefauver supporter? How far did he go to advance Kefauver’s nomination, and why couldn’t he make it happen in the end?

It’s a complicated story, so let’s dive in.

A Crusader with High Ideals – and Sharp Claws

Drew Pearson was the biggest political columnist of his day. At his peak, his “Washington Merry-Go-Round” column ran in over 650 newspapers, more than twice as many as his nearest competitor. An estimated 60 million Americans read his words. And he didn’t just appear in newspapers; he also hosted radio and television broadcasts.

Like Kefauver, Pearson’s fame transcended his profession. He appeared in multiple Hollywood movies, including “The Day the Earth Stood Still” and “City Across the River,” playing himself. He was the subject of jokes on legendary comedian Jack Benny’s show. He even edited a comic strip, “Hap Hopper, Washington Correspondent,” which was (very loosely) based on his own adventures.

In person, Pearson was courteous, gentle, and soft-spoken. In his columns, he was aggressive, ruthless, and merciless.

He saw himself as a crusading reporter in the tradition of the turn-of-the-century muckrakers like Jacob Riis and Ida Tarbell. He was a practicing Quaker, and his religious beliefs informed his approach to reporting. As his protégé Jack Anderson explained, Pearson sought “to help what he saw as the humanitarian cause and to hurt those who thwarted it – imperialists, militarists, monopolists, racists, crooks in public and corporate life, all of whom he saw as subverters of the American system and exploiters of the poor.”

Pearson was a committed pacifist. He made an exception for World War II, understanding the importance of combatting fascism, but spent the rest of his life leading campaigns to spread democracy and peace around the world. He barnstormed around the country to collect food and clothing for the victims of World War II in Europe and to raise money to aid victims of racist violence in America.

If this makes Pearson sound like a saint, think again. When writing about people and groups he considered enemies of the common good, he went after them with unrestrained viciousness. “On the attack he was unremitting,” Anderson explained, “and even when not mortally engaged, he thought it salutary that the mighty should be humbled.”

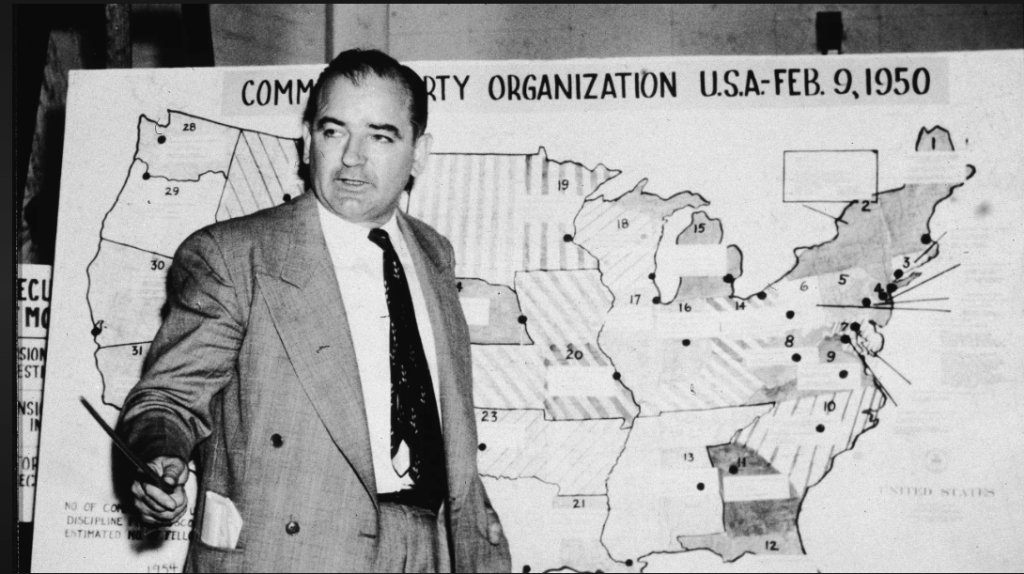

He didn’t just write a single column to attack an enemy; he wrote dozens. During his 1950 crusade against Joseph McCarthy, Pearson penned a total of 40 columns attacking the Wisconsin Senator, backed up with a string of critical radio broadcasts. (In response, McCarthy assaulted Pearson in a Washington club, capping it off with a knee to the groin. He also drunkenly fantasized about “bumping Pearson off.”)

There were few lines that Pearson wouldn’t cross in his reporting. He had no compunction about publishing secret information leaked to him, and he didn’t hesitate to air his enemies’ dirty laundry. When General Douglas MacArthur announced plans to sue Pearson over a critical column, the columnist threatened to publish MacArthur’s letters to his mistress; the famously feisty general backed down.

Pearson placed principle above business interests. He went hard after McCarthy even though the Senator regularly leaked to him about the inner workings of Congress. Anderson tried to get Pearson to drop his crusade by warning, “He is our best source on the Hill.” Pearson replied, “He may be a good source, Jack, but he’s a bad man.”

He didn’t carry libel insurance and wouldn’t let his syndicate bankroll his defense of libel suits (on the theory that it would give them leverage to censor him). Pearson was sued frequently – 120 times, in fact – but he only ever had to pay a settlement once.

In many ways, Pearson was a political gossip columnist; it was his inside-baseball nuggets that made him so popular. But he didn’t just consider himself an observer; he wanted to influence the news as much as he wanted to report on it.

He regularly sent notes to Senators and Congressmen, calling on them to vote for bills he favored. He relayed messages between major figures of both parties. He even served as an unofficial envoy between the US and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, hosting parties with Soviet officials at his home and fostering off-the-record conversations.

During Presidential campaigns, Pearson went all out – publicly and privately – to boost his favored candidates. And Kefauver was one of his all-time favorites.

1952: Kefauver’s Secret Strategist

In retrospect, it’s not surprising that Pearson supported Kefauver so strongly. They saw eye-to-eye on a lot of issues. They were both proud liberals who shared a strong belief in free speech, world peace, public and private ethics, and skepticism of monopoly. As Southern politicians went, Kefauver was good on civil rights; he raised money for Pearson’s “Americans Against Bombs of Bigots” and “American Conscience Fund” campaigns.

Kefauver also shared Pearson’s idealism about government, and he was generally unwilling to compromise his principles to get ahead. Surveying the potential candidates in early 1952, he wrote that “I would prefer Kefauver to Eisenhower,” stating that “Kefauver has the know-how and the idealism.”

From the very beginning of Kefauver’s 1952 campaign, Pearson recognized the challenges the Senator faced. “On the face of it, I don’t see how Kefauver can win the nomination unless he gets an organization.” Pearson wrote in his diary. While he admired Kefauver for “fighting a completely one-man battle,” he understood that this wouldn’t win him the nomination.

Pearson stepped in as an unofficial campaign strategist and emissary. Before Kefauver hired Gael Sullivan as his campaign manager, Pearson acted as a matchmaker between the two. (He thought Silliman Evans, publisher of the Nashville Tennessean, might be a better choice, but he worried about Evans’ sobriety.)

During the primaries, Pearson wrote a couple of campaign speeches for Kefauver, at the candidate’s request.

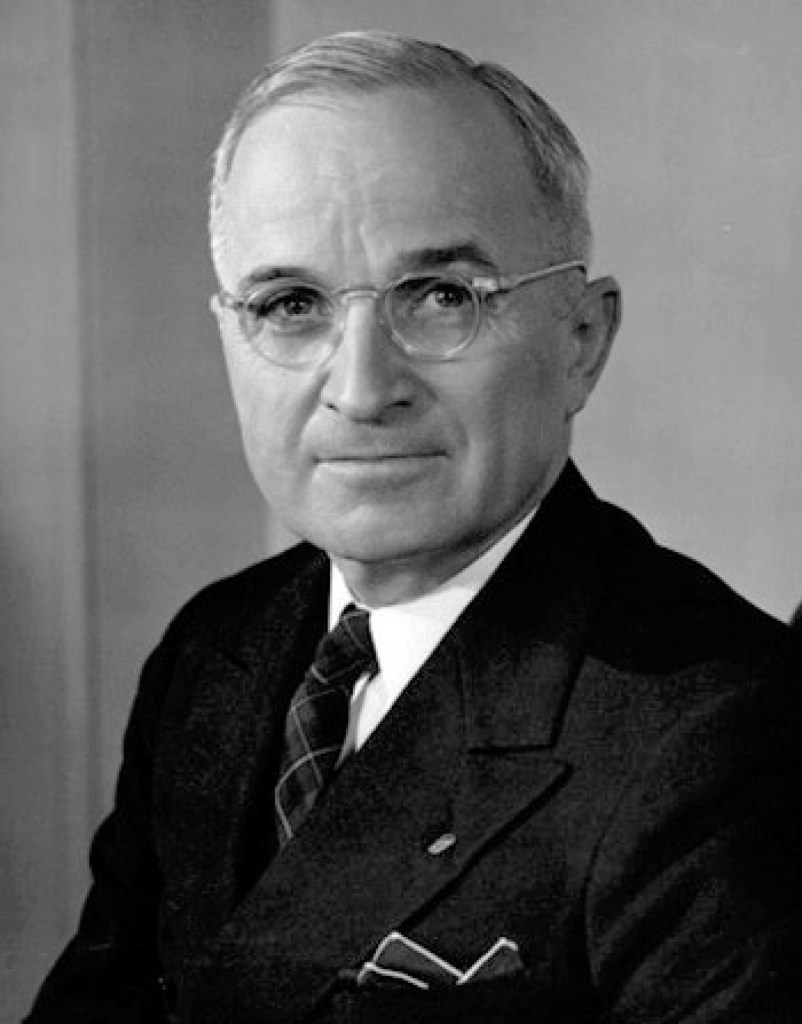

Pearson’s most important function, however, was his ongoing effort to soften Harry Truman’s opposition to Kefauver’s candidacy. He knew that the outgoing President would be a huge stumbling block, writing in his diary that “[t]he palace guard is so vindictive” that Truman became angry even hearing favorable mentions of Kefauver.

As the convention approached, Pearson held back-channel discussions with Truman staffers Clayton Fritchey and Oscar Chapman, hoping they would warm their boss up to a Kefauver nomination.

Pearson made sure the staffers told Truman every time Kefauver praised him on the campaign trail. He passed along the text of speeches to show how much Kefauver aligned with Truman on policy. In return, Chapman and Fritchey suggested that Truman was coming around, or was at least persuadable.

When Pearson arrived at the convention, he found that “Truman is bitterly resentful against Kefauver,” as he wrote in his diary, noting that Chapman and Fritchey “were either kidding me or else ignorant of the facts when they thought he was being warmed up.”

Realizing the height of the hurdles Kefauver faced, Pearson went into overdrive. He lobbied Averell Harriman’s supporters to get their man to withdraw in favor of Kefauver. On his television show, he charged that Frank Costello and other mob figures were pulling strings to defeat Kefauver. He collaborated with Western Union to run a snap “People’s Poll,” in which 73% of respondents favored the Senator from Tennessee.

It all came to naught in the end, and Pearson was nearly as disappointed about Kefauver’s loss as the candidate himself. In his diary, he described the convention as “democracy in the rough” and added, “The political bosses don’t seem to realize that everything they do and say is recorded before the eyes of millions of people.”

1956: Pearson Takes Politics Over Principle

When Kefauver made a second try for the Presidency in 1956, Pearson was again in his corner. He supported Kefauver strongly enough to bend on his prized journalistic principles.

In the middle of the primary season, Lyndon Johnson approached Kefauver’s campaign manager Jiggs Donahue with a deal.

Pearson frequently criticized LBJ for being too beholden to oil and gas interests. Privately, Pearson justified the attacks by saying, “I’ve got to have someone among the Democrats to criticize and he is, after all, the leader… Furthermore, when any politician gets in high position he has to be fair game.”

That spring, Pearson was investigating the Majority Leader’s moves to help Brown & Root, a Texas-based construction company, evade taxes. LBJ found the accusations vexing, so he made Donahue an offer: If Pearson would drop the investigation, Johnson would back Kefauver for President.

The columnist agreed, albeit with reservations. “This is the first time I’ve ever made a deal like this,” he wrote in his diary, “and I feel a little unhappy about it.” He also expressed skepticism that LBJ would hold up his end of the bargain. (That skepticism was justified: Johnson never lifted a finger to help Kefauver’s bid.)

In the end, though, he decided “I ought to do that much for Estes… With the Presidency of the United States at stake, maybe it’s justified, maybe not – I don’t know.”

When Kefauver’s campaign approached its end, Pearson again played a critical role. After Kefauver lost the Florida and California primaries, he had to decide whether to drop out or keep fighting to the convention floor.

Pearson served as an emissary to Adlai Stevenson, gauging Stevenson’s willingness to offer Kefauver the VP slot in exchange for the Tennessean’s endorsement. Stevenson waffled and ultimately refused to commit. Pearson wrote in his diary, “Stevenson’s friends are right that he’s a very difficult guy to pin down and has trouble making up his mind on anything.”

Before Kefauver made a final decision, he met secretly with Pearson. The columnist privately thought Kefauver should stay in the race, but after realizing Kefauver was inclined to withdraw, he told him “I thought it was the hardest decision in the world to make and whatever he did his friends would be with him.”

The Would-Be Power Broker Comes Up Short

While Pearson was particularly close to Kefauver, he had similar relationships with many Democratic Senators (though not to the point of being shadow campaign managers for their Presidential runs). It demonstrates how much cozier the relationship between politicians and reporters was in that era – and how Pearson, in particular, blurred the line between journalism and politics.

So if Pearson was so influential, why couldn’t he get Kefauver the nomination? For one thing, he and Kefauver had a similar problem: their popularity with the people didn’t translate to pull with the political bosses. Truman and LBJ wanted Pearson on their side, but his influence wasn’t enough to overcome their antipathy to Kefauver.

Relatedly, like Kefauver, Pearson’s idealism got in the way of his ambitions. Successful candidates like Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson had hard-charging henchmen on their side who would do the necessary dirty work to boost their guy’s chances. (Even Stevenson, the lofty patrician, had the Chicago political machine working on his behalf.)

Kefauver didn’t have people like that, nor would he have wanted them. That fundamental nobility was a key reason Pearson admired him. But it’s also a key reason why, in the end, they both wound up on the sidelines as other men walked away with the prize they sought.

Leave a comment