Americans love to talk about freedom. We boast about being “the land of the free,” with justifiable pride. But if there’s one thing we love more than celebrating our freedoms, it’s arguing about them.

Whenever we find ourselves in a crisis – real or perceived –some people find the broad scope of our liberties inconvenient, and argue that they should be suspended or curtailed in the name of security.

The beginning of the Cold War was such a crisis. A lot of Americans were deeply concerned about Communist infiltration, and believed we needed to take extraordinary measures to identify and root out suspected Communists.

Textbooks (and even the Girl Scout Handbook) were scrutinized for left-wing sentiments. Government workers, teachers, and union leaders were subjected to rigorous background checks to see if they had ever been Communists, or hung out with them. The mere suggestion that someone had Red leanings was enough to ruin reputations and cost people jobs.

Critics – like Estes Kefauver – pointed out (correctly) that these measures impinged on our First Amendment rights of free speech and assembly. Anti-Communists countered that the Red menace was so threatening that these measures were vital for America’s safety.

In the summer of 1949, Alger Hiss was tried for lying to the House Un-American Activities Committee about his alleged participation in a Soviet spy ring. The trial sparked nationwide debate – both over his guilt or innocence, and about the hunt for Communists in government and its effect on Americans’ rights and freedoms.

That July, Kefauver duked it out with Republican Senator Karl Mundt on a national radio program called the University of Chicago Round Table. This was a weekly panel show in which experts in a variety of fields discussed the big questions of the day.

Three days after the Hiss trial ended, the Round Table held a discussion with the provocative title, “The Condition of American Liberty Today.”

Both Senators were able advocates for their respective views. Mundt had been on HUAC for five years; he believed that America’s security depended on weeding out Communist influence, but he wasn’t a demagogue like Joseph McCarthy or William Jenner.

Meanwhile, Kefauver had already established a reputation as an outspoken champion of civil liberties. While he was opposed to Communism, he was deeply concerned about crackdowns on speech and dissent.

The debate was moderated by U. of C. professor Walter Johnson, a political historian – emphasis on “political.” Johnson did not believe that academia and politics should be separate, and he was active in Democratic politics.

Fighting the Communist Fire… or Playing Into Their Hands?

Johnson opened the discussion by asking the Senators whether they were “alarmed or confident about the condition of American liberty today.” Both were alarmed, but for very different reasons. Their answers – Mundt’s in particular – were highly illuminating.

Mundt painted a dark picture of the growing influence of Communism around the world, claiming that “the areas of liberty and freedom are being slaughtered, both economically and politically.” He argued that political liberty was dependent on economic liberty (that is, free-market capitalism), stating that “almost only in the Western Hemisphere is private enterprise being practiced vigorously.” To Mundt, the imminent threat of Communism justified curtailing American freedoms in the name of security.

Kefauver acknowledged the threat, but he countered that reducing the rights and freedoms of Americans was essentially doing the Soviets’ work for them. “[W]e are letting Joe Stalin have too much of a part in running our country,” he said.

Kefauver painted a broader view of American freedoms than Mundt, focusing heavily on First Amendment rights. “In America the great word is ‘freedom’ – freedom of speech, religion, assembly, and thought,” he said.

Johnson cited other historical incidents of speech suppression in America, including John Adams’ Alien and Sedition Acts, the silencing of anti-slavery voices in the South in the run-up to the Civil War, and the Red scare in the wake of World War I.

Johnson didn’t connect the dots, but he underscored an important point. America had been (relatively) willing to tolerate suppression of liberties during wartime or in moments of crisis. But the Cold War had no actual battles; it could (and did) go on for decades.

This was the same point Kefauver made in his minority report on the Korean War ammunition hearings: the country cannot remain on a war footing indefinitely, just in case fighting breaks out. “Emergency measures” cannot be employed for an emergency that never ends.

Instead, pointing out that America was now the world’s richest and most powerful country, Johnson asked: “[J]ust what are we afraid of, gentlemen,” he asked, “in relation to this whole area of American liberty?”

Mundt didn’t feel like answering the question; instead he picked on something Kefauver had said earlier. The Tennessean had complained about the headlines being dominated by spy trials and accusations of Communism, a sign of America’s unhealthy obsession with the Red menace.

Mundt countered that the great San Francisco fire of 1906 also dominated the headlines – not because the country was obsessed with fire, but because it was a catastrophic disaster. He said that Communism would continue to dominate the news “until we have stamped [it] out of government and get it out of high places.” Again, Mundt framed Communism as a massive threat that justified extraordinary measures in response.

Kefauver replied that we should focus on demonstrating the superiority of the American system, which meant that “we ought to be sure that we protect freedom of speech, freedom of difference of opinions, freedom of assembly, and freedom of religion – the great freedoms that we have in this country.”

Debate Part 2

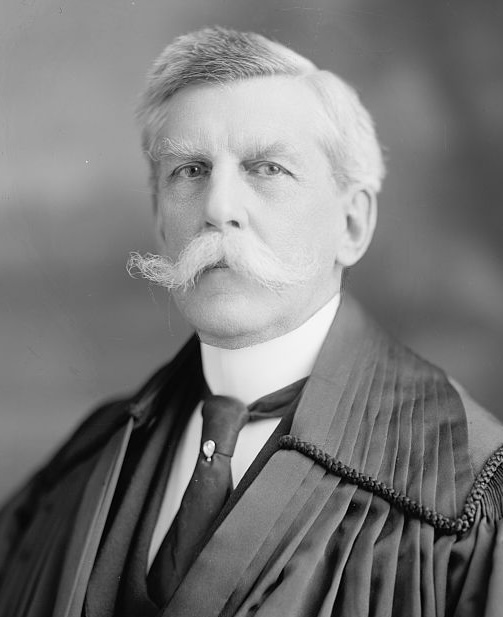

Johnson went after Mundt’s repeated insinuations that Communism was an existential threat, citing Oliver Wendell Holmes’ doctrine that government could only restrict speech that presented a “clear and present danger.” Did the Cold War represent such an imminent danger?

Kefauver argued that it did not, and pivoted to one of his favorite topics: the danger of squelching dissent. “I have been worried… that we have a feeling in this country today that we cannot disagree with one another,” he said. He pointed out that one major criticism of Communism is that it outlaws and punishes dissenting opinions. “We ought to be very sure that we do not fall into the same difficulty here.”

Mundt countered that he was an expert on dissenting opinions, having been in the minority for his entire time in Congress. “I have felt perfectly free to criticize the President or the party in power or any policy,” he said, “and I would just like to have somebody point out to me who and where anybody has been denied freedom of speech in this country.”

Kefauver provided an example of a Republican Senator who announced his opposition to the formation of NATO. Another Republican criticized that Senator for “following the Henry Wallace line.” (Wallace, whom Republicans considered a crazy left-winger, was a vocal opponent of NATO.) Kefauver objected to “just labeling the fellow who disagrees with you with some bad name or some alien philosophy.”

This was a noble example from Kefauver, since he – like Mundt – was a strong NATO proponent. However, he supported his colleague’s right to disagree.

Mundt couldn’t help himself; pointing out that Wallace had been FDR’s Vice President, he said it was “interesting” that Kefauver thought that saying someone agreed with Wallace “makes him an alien and a bad fellow.” Kefauver replied that that wasn’t his point. “I disagree with Mr. Wallace,” he said, “but I am not going to say Mr. Wallace is alien to our philosophy or that he is a Communist.”

Taking a prompt from Johnson about guilt by association, Kefauver cited his campaign for Senate as an example: “[W]herever it could be found that I may have voted (although many other people did) with a certain member of Congress, certain people have always linked my named with his name,” he said. This was a reference to Vito Marcantonio, the socialist Congressman from New York, a frequent Republican bogeyman of the era.

He also complained about accusations ginned up from information in “secret files.” He mentioned TVA director Gordon Clapp, whom the Army deemed “unemployable” for a job reconstructing postwar Germany, but refused to explain why. (When the story hit the news, the Army apologized and said it was a mistake.)

Kefauver pointed out that Clapp was cleared only after it became a national story. “[I]f that had been some long-haired professor, way out in some college, this matter might never have been clarified,” he noted.

Johnson asked whether the Senators thought too many issues were judged on whether they were deemed pro- or anti-Communist, rather than on their merits.

Mundt said that this was inevitable, because “communism is the big threat to freedom. It is the big threat to liberty. It is the big threat to peace.” Given the massive scope of the problem, he concluded, “I do not think that Congress, or the country, can be criticized for paying considerable attention” to the issue.

Kefauver countered that “we ought to get down to the merits of what we are doing, and not just vote for a thing or against it wholly on the basis of whether or not it is going to deter communism.”

Johnson started a good question on what could be done to strengthen American liberty, but then stepped on it by challenging Mundt about HUAC’s actions to investigate college textbooks and demand loyalty oaths from teachers. Since Mundt was opposed to both actions, the question wasn’t as fruitful as Johnson hoped. Mundt and Kefauver both agreed that loyalty oaths were useless, because actual Communists would simply lie.

Kefauver affirmed his belief that we should “let students and the educational field find out about anything they want to.” Mundt endorsed a proposal from Dwight Eisenhower (then president of Columbia University) “that teachers not be employed if they are Communists.” A typical Ike sentiment: nice in theory, but hand-waving away the details.

Johnson wrapped up the discussion by asking the Senators whether they agreed with Woodrow Wilson’s statement: “‘The most patriotic man is sometimes the man who goes in the direction that he thinks right even when he sees half the world against him.”

Mundt conceded that it was occasionally true, but “the most patriotic man is usually the man who conforms with the program that his country has worked out.” Kefauver stressed that “we must be careful… not to label a person a bad name just because he may dissent. We ought to encourage dissent.” Both Senators agreed that “dissension is part of democracy.”

A Worthy Debate… and An Ongoing Crisis

Overall, both men ably argued their point of view. It will not surprise you to learn that I side with Kefauver. Our First Amendment freedoms are sacred, and we should only seek to limit them in the most dire emergencies, which the spread of Communism was not. And as Kefauver said, we should encourage criticism and dissent, not seek to stifle it.

Unfortunately, the situation would get worse before it got better. Joe McCarthy wasn’t even on the national radar screen yet. Hysteria about the Red threat in our midst would only intensify in the early 1950s. (Even during this debate, Kefauver felt the need to remind the audience that he was against Communism roughly every third sentence.)

I’d also note that after the transcript, the University reproduced a speech from their Chancellor, Robert Hutchins, entitled “The American Way of Life,” delivered at that year’s convocation. It’s an eloquent, brilliant defense of American rights and freedoms… and it’s 100% on Kefauver’s side of the argument.

Johnson, the moderator, clearly also agreed with Kefauver’s views on freedom. I think that Johnson did a good job moderating the discussion despite his obvious partisan slant. As to his credit, Mundt didn’t complain about it.

But I can only imagine how Republicans would react today if a TV show featured a debate with an openly Democratic moderator and, at the end, they read a 2000-word essay endorsing the Democrat’s viewpoint. It was different times, let’s just say.

Leave a comment