Recently, I added a new button to my Kefauver collection. The button represented a group I’d never hear of before: TASK, or “Teen-Agers for Stevenson-Kefauver.”

As I researched the story behind the button, the tale of TASK opened up a larger story about young people’s participation in politics. The 1956 election marked the beginning of campaigns understanding that even though teenagers weren’t allowed to vote, they cared about politics and wanted to be involved.

TASK seems to have originated in the suburbs of New York City. A Big Apple-based group calling itself “Teen-agers for Stevenson” attended the Democratic convention in Chicago that August; they were credited with creating with Doc Quigg of United Press called “a wild new bebop-type slogan” for Stevenson, “Madly for Adlai.”

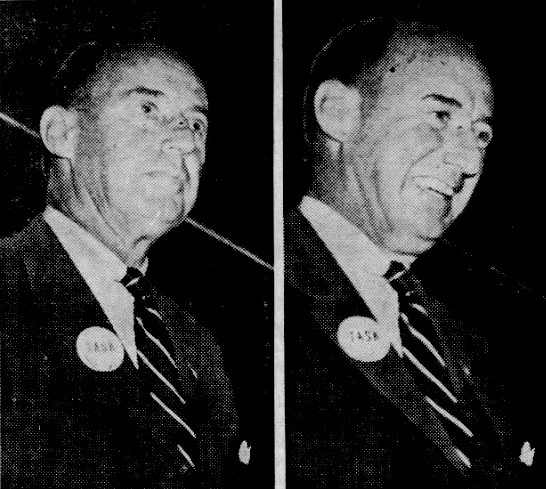

Following Stevenson’s nomination and the kickoff of the fall general election campaign, students at Great Neck High School formed the initial chapter of TASK. They made their official debut on September 11, welcoming Kefauver as he visited the campaign’s headquarters in New York City to kick off Mayor Robert Wagner’s campaign for the US Senate.

From its beginnings in Great Neck, TASK quickly spread throughout the metropolitan area. Chapters were founded in Mount Vernon, Yonkers, Nassau, and Roslyn. They even crossed state lines, with a TASK chapter starting up in Paterson, New Jersey.

TASK, which was open to teens between the ages of 13 and 18, offered politically active students the opportunity to volunteer with the campaign. They started out raising money for Stevenson-Kefauver by selling TASK buttons for a quarter a pop. In time, they began canvassing door-to-door, handing out literature and soliciting donations. They offered to serve as babysitters, freeing up parents to go register and vote or do some campaigning on their own. Those who were old enough to drive offered rides to the polls.

On nights when Stevenson was speaking on TV, TASK members formed “balloon squads.” They walked the streets and stood outside train stations, handing out balloons with the time and channel of Stevenson’s speech.

When Stevenson spoke in Levittown on October 24, female TASK members served as ushers to help crowd members to their seats. (They had their hands full; the event drew a standing-room-only crowd of over 5,000 people, and the campaign wound up having to lock the venue doors by order of the fire department in order to keep the overflow crowd out.) In return for their enthusiasm, Stevenson wore a TASK button on his lapel during his speech.

TASK boys and girls also joined the candidate on a parade through the streets of Westchester County.

It wasn’t just Democratic teenagers getting active, either. After the formation of the initial TASK chapter at Great Neck High, the school’s Republican students formed a rival club called TEEN (Teens for the Election of Eisenhower-Nixon). In mid-October, members of TASK and TEEN held a debate on the theme “What Our Party Has Contributed to Our Future,” which was broadcast on a local radio station.

TASK and TEEN generated enough excitement that Great Neck High wound up holding a mock election a couple days before the real thing. Presumably thanks to TASK’s tireless efforts, Stevenson emerged victorious, 838 votes to 754. (In the actual election, Eisenhower cleaned up, claiming over 61% of the vote in New York State. Nassau County, where Great Neck was located, was even redder: Ike got 69% of the vote there.)

TASK seems to have been confined to the NYC metro area. There was a group calling itself “Teen-Agers for Stevenson-Kefauver” that formed in North Carolina, but its organizers had no apparent knowledge of the New York TASK chapters. In fact, Lorenzo Smallwood (chairman of the Haywood Country Democratic Executive Committee and leader of the North Carolina effort) said, “We believe this is the first time that teen-agers under voting age have been actively organized to aid in a get-out-the-vote campaign.”

Is all of this just a historical curiosity? I don’t believe so. Rather, it’s the beginning of the rise of teenagers as their own distinctive demographic, both within politics and in the culture more generally.

As I read about TASK’s story, I recalled my interview with Fred Strong, and how he became involved with politics as a teen. When he called up his local Democratic Party chapter after the 1952 election and offered to volunteer, they literally had no idea what to do with him and wound up sending him to the local college. The idea of high schoolers participating actively in politics was an alien concept.

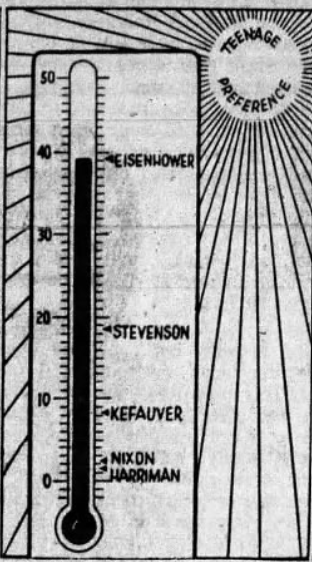

In 1956, that started to change. TASK and TEEN were a sign of that. But so was a survey done that summer by Gilbert Youth Research, an organization dedicated to the study of the “ideas and attitudes” of teenagers. The organization surveyed teenagers on their political views, and Eugene Gilbert (the firm’s president) wrote up the key findings of the survey in a nationally syndicated article that ran in early August.

Gilbert found that teenagers favored Eisenhower over Stevenson by roughly a 2-to-1 margin. (It’s not clear when the survey was done; roughly 8% of the student favored Kefauver, while a couple percent opted for Nixon or Averell Harriman.) Unsurprisingly, he discovered that many of the teens favoring Ike were fond of him personally, and did not consider themselves Republican partisans.

Gilbert explored the question of lowering the voting age to 18. Unsurprisingly, the idea was widely popular with teens; 96% of those surveyed favored the idea. However, only 51% of them said they would vote if they could, leading Gilbert to huff that “their interest seems to be in satisfying their ego, not in joining in running the government.”

Gilbert’s crack was hardly fair; the teens themselves explained their lack of interest in voting. Many of them felt that Eisenhower was so certain to win that their vote was meaningless, while others contended that the parties’ positions were too similar to matter.

Gilbert’s survey found that 80% of teenagers supported the same candidate as their parents, but many of them claimed that their parents’ preferences didn’t influence their own choice. This was an important point, as one of the arguments against teen voting was that the teens would just parrot their parents’ views unthinkingly. Gilbert’s survey demonstrated that this wasn’t the case.

Whether the adults of the day were ready to accept it or not, it was becoming clear that America’s teenagers were developing their own voices and opinions. And politicians recognized that they would benefit from engaging them in campaigns, despite their inability to vote.

As Newsday put it in an article about TASK and TEEN, “Candidates who have paved the highways to political success with the help of the farm vote, the labor vote or big business soon may find themselves beating a path to the door of America’s newest minority group – the teenage population.”

For Kefauver, of course, this was nothing new – he’d been speaking to and encouraging young audiences for years. But the political mainstream was starting to catch on. And the teenage voices would only become louder – and more independent of their parents – as time went on.

The 1956 election marked the first stirrings of the great teenage political awakening. Within a few cycles, those stirrings would turn into a full-on earthquake.

Leave a comment