The Korean War is often called the “Forgotten War,” and with good reason. It was neither a soaring triumph like World War II, nor a scarring national controversy like Vietnam. The war never even technically ended; it concluded in an unsatisfying armistice. It didn’t serve any of our national narratives, so we moved on.

But the war was a subject of intense debate at the time. And for several months in 1953, a Congressional subcommittee investigated a somewhat curious subject: allegations that the military ran short of ammunition during the war. The hearings allowed a look back, as America came to terms with a war that didn’t end in resounding victory. They also allowed a look forward; with the Cold War looming, the country had to decide how much of the economy to devote to preparations for the next battle – which could be next week, next year, or decades away.

Estes Kefauver was a member of the subcommittee. During the hearings, he showed that his performance in the organized crime hearings was no fluke. He thoughtfully questioned military leaders without flinching, and he stood up to the rest of the subcommittee when they tried to engineer the result they wanted.

Over the next three weeks, we’ll take a look back at the hearings. This week, we’ll focus on how and why the subcommittee came together

Searching for a Scapegoat

One of the key reasons Dwight Eisenhower was elected President in 1952 was public dissatisfaction with the course of the Korean War. When America parachuted in to defend South Korea against Communist invasion in the fall of 1950, military leaders assured us the war would be over by Christmas.

Instead, the war turned into a grinding stalemate; we were neither able to achieve victory nor negotiate an armistice. The American people were left confused and disheartened.

Once Eisenhower was in office – bringing with him Republican control of both houses – his party was eager for two things: to bring the Korean War to an end as soon as possible, and to blame Harry Truman for the whole thing.

Not long after becoming Senate Majority Leader, Robert Taft called for the creation of a special committee to examine all aspects of the war, from alleged supply shortages to the stalled armistice talks to the treatment of POWs.

This was a transparent attempt to beat the dead horse of the Truman administration. Kefauver perceived this immediately and pushed back, charging that Taft’s committee would “plunge the conduct of the war into politics.”

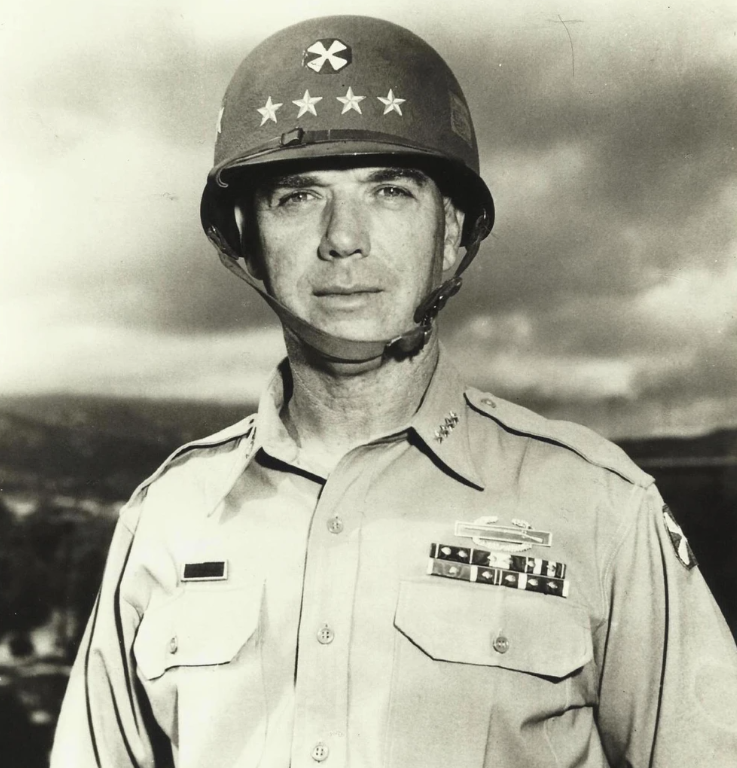

Taft quickly abandoned his proposal, but the GOP soon found a new opportunity when General James Van Fleet, who had recently retired as commander of the Eighth Army Division in Korea, testified to Senate Armed Services on March 5th that ammunition shortages had hampered his ability to wage war successfully.

The Army denied Van Fleet’s charges, saying that the troops had been adequately supplied with ammunition throughout the course of the war. But Republicans didn’t care; they had their issue! They hastily assembled a subcommittee to hold hearings into Van Fleet’s serious, serious charges.

The subcommittee would be chaired by Senator Margaret Chase Smith of Maine. On paper, she seemed the ideal choice as chair. Not only was she a loyal Eisenhower supporter, but she was also a known admirer of Van Fleet; she had written in support of Ike naming him as Army Chief of Staff, saying that Van Fleet would take the situation in Korea from “stalemate to… pressing for an end to the war.”

The other Republicans on the subcommittee, Robert Hendrickson of New Jersey and John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky, were unlikely to buck the majority on defense issues. And the senior Democrat, Virginia’s Harry Byrd, was arguably the most fiscally conservative member of the subcommittee.

This seemed like a golden opportunity for the new GOP majority to score some political points. It didn’t quite work out that way, for three reasons. First, Eisenhower and the subcommittee wanted different things from the hearing. Second, their star witness had his own agenda. And third, they invited Kefauver to the party.

You Can’t Always Get What You Want

Spoiler alert: There was no ammunition shortage in Korea. Individual units might have run out of certain types of ammunition for short periods, but there was never any danger of overall supply shortages. And after a bit of a slow start, by 1952 American industry was producing more than enough ammunition for the Army’s needs.

So why did Van Fleet claim otherwise? Well, there’s a couple of important things to understand about him.

First, he really liked big showy displays of artillery fire. Less than a month after taking over command of the Eighth Army in the spring of 1951, Van Fleet ordered the artillery units to increase their firing rate by 500%, a display of pyrotechnics that became known as the “Van Fleet Day of Fire.”

Second, Van Fleet really, really wanted to escalate the war. As he testified to the subcommittee, “The only solution is a military victory in Korea.” He believed the drawn-out stalemate and the stalled negotiations were killing the troops’ morale. He argued that an armistice that divided Korea in half would only “postpone the agony,” since the Chinese and North Korean troops could march right down and capture Seoul in a day once the Americans left.

Van Fleet’s desire for a wider war was nothing new. He’d been lobbying for more aggressive action in Korea during his entire command there. Believing that Eisenhower saw things his way, Van Fleet went all in on helping Ike get elected, going to far as to send the candidate a letter for campaign use attacking Truman’s management of the war.

So Van Fleet’s claim of ammunition shortages was likely a cover for what he really wanted to talk about: expanding the war.

Kefauver believed the alleged ammunition shortage a worthy subject for Congressional investigation. “I am not satisfied with the Pentagon’s denial of charges by General Van Fleet that there has been a shortage of ammunition in Korea,” Kefauver told reporters in mid-March. But he was horrified by the idea of escalating the war. He told reporters that extending hostilities into mainland China would “touch off World War III in the Orient.”

As determined as Van Fleet was to make the case for a wider war, Kefauver was equally determined to stop him.

Kefauver wasn’t the only one who had different priorities than Van Fleet. Eisenhower wanted to bring the war to a close as quickly as possible. He wasn’t averse to escalation – up to and including tactical nukes – in order to move armistice negotiations along. But he wasn’t rushing to attack mainland China, as Van Fleet hoped.

More importantly, Ike was looking for ways to cut defense spending. In February, he told the National Security Council that he had no interest in “bankrupting the country” with defense spending. In early March, Ike’s Bureau of the Budget unveiled a plan that featured deep cuts to the armed forces, including a plan to reduce the Army from 20 divisions to 12.

Eisenhower was fine with the subcommittee pinning blame for the Korean situation on the Truman administration. But he wasn’t particularly interested in any suggestions that might increase the defense budget, and he was ready to ambush the subcommittee if the proceedings weren’t going the way he wanted. The subcommittee would find this out the hard way.

We’ll dive into that next week, when we look at the hearings themselves.

Leave a comment