For a politician famed for his skill as a campaigner, it’s surprising that Estes Kefauver didn’t have a well-known slogan.

In his first run for the Senate in 1948, he used “Peace and TVA.” But as a Presidential candidate, he never managed to get a particular slogan to stick, certainly nothing to compare with “I Like Ike.”

It wasn’t for lack of trying. In his two Presidential runs in 1952 and 1956, Kefauver used multiple slogans, including “Clean Up Crime and Corruption,” “A Democrat Who Can Win,” “The People’s Candidate,” “A Great American,” and “Estes Is Bestes.” None of them really stuck, though. If there was a phrase associated with him, it was the homely line he delivered with his famous handshake: “I’m Estes Kefauver. I’m running for President, and I’d appreciate your help.”

He tried hardest on the slogan front in 1956, leaning in on the concept of “an even break.” In the end, it proved no more effective than the others that he tried. But I can understand why it appealed to him. Kefauver’s campaign was all about the desire for a fair shot… both for the American people, and for the candidate himself.

The Idea Takes Hold

Kefauver started using “even break” from the very beginning of the 1956 campaign. While stumping in the snows of New Hampshire in mid-January, he was already incorporating it into his speeches.

He promised a Rochester crowd he’d enact “a program which will give everybody an even break.” In Manchester, he drew thunderous applause by speaking of his “great ambitions for our country,” which included ensuring that “the farmer and the small businessman will get an even break.”

Speaking to the California Democratic Council in Fresno in early February, he fleshed the idea out further. “What we need most in Washington and the nation, it seems to me, is a climate favorable to the common man,” he said. “Favoritism in taxes, in regulations, in contract awards – in all the ways in which government may express it – must give way to the philosophy of the even break – and especially an even break for the common man.”

He sharpened his attack on the Eisenhower administration at a banquet in Michigan the following week. “You know as I know that the record of the Republicans has been a record of favoritism to special interests,” he said. By contrast, Kefauver said the Democrats stood for “the policy of the even break for every American. I want the little man to be given the same break that the big man now receives under the Republicans.”

Solidifying the Slogan

By the time Kefauver scored back-to-back wins in the New Hampshire and Minnesota primaries in March, he had firmly seized on the “even break” as a theme of his campaign.

Campaign communications chair Lou Poller noted after New Hampshire that the slogan “An Even Break for Every American” resonated with the voters. “The slogan includes all Americans… with an even break for everyone but an edge for no one person or group,” Poller told the Scranton Times-Tribune.

After Kefauver’s shock win in Minnesota, the campaign found itself (by its shoestring standards) flush with contributions. They used the windfall to invest in the sort of political tools they hadn’t been able to afford previously, hiring a Washington ad agency named Kal, Ehrlich & Merrick.

“Advertising experts are busy weaving a new slogan – ‘Get an Even Break With Kefauver’ – into campaign material,” wrote the Washington Evening Star’s Tait Trussell. (The slogan was hardly new at this point, but never mind that.)

Trussell reported that the slogan was being applied to “[s]lick brochures for campaign workers, film strips for television, [and] recorded spot ‘commercials’ for radio,” as well as “a portfolio for key supporters to use where Mr. Kefauver can’t get close enough to touch or talk to a voter.”

In the TV and radio commercials Trussell explained, “a purported farmer, businessman or what-have-you asks a question on a current issue and the Senator replies, working in the ‘even break’ whenever possible.”

Staying firmly on message, Kefauver summed up his pitch to Bob Considine of INS by saying, “I stand for an even break for every American.”

As the campaign shifted to the critical showdown states of Florida and California, Kefauver continued to hit the theme.

In Stockton in mid-April, he vowed: “You may be sure labor is going to get an even break, fairly and squarely all up and down the line, if I’m elected president of the United States.”

Speaking to senior citizens in Los Angeles, he promised to bring back a government that would “once again…give an even break to the ordinary citizen” and was “willing to think in terms of people as well as in terms of statistics and the dollar sign.”

He promised a Tampa crowd that “I’m going to see that our working people get an even break,” emphasizing that “[l]abor is not entitled to anything special, but they are entitled to be treated fairly.”

In between, he made a televised speech in Indianapolis stating that “all the people realize their best chance for a fair, even break is with the Democratic party.”

The Presidential Bid Ends, But the Slogan Lives On

Even after Kefauver ended his Presidential campaign, he kept using the “even break” theme as Adlai Stevenson’s running mate. Kicking off the fall campaign in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania in September, Kefauver summed up the Democratic philosophy simply: “We believe in an even break for all men,” he said, noting that this “should be the dominant concern of government.”

By contrast, he charged, Republicans stood for “the bad break, the weighted tax law, the stacked government commission, the inside track which runs the distance from Wall Street to the White House. They have introduced privilege, preference, and personal priority into the machinery of government.”

He hit the same notes in Milwaukee, saying that Democrats believed in “giving the people a fair and square break,” while Eisenhower and the Republicans were “dedicated to favoritism to special interests.”

Why Didn’t It Stick?

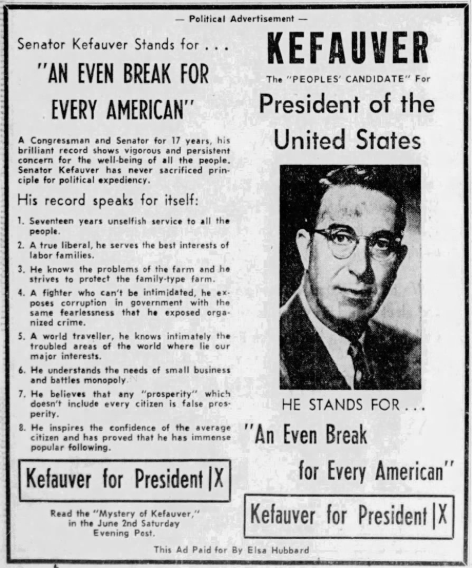

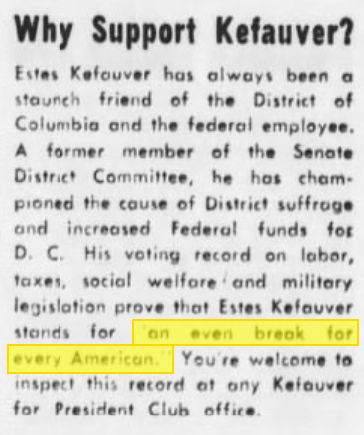

Despite his repeated invocations of the slogan, Kefauver never really became associated with the “even break.” To understand why, take a look at one of his brochures from the 1956 campaign (this shot shows the front and back of the brochure):

As you can see, his “An Even Break for Every American” slogan features prominently here. But so does “This Democrat Can Win in ’56!”, which stands out because it’s in red. And even his old “Peoples’ Candidate” motto pops up as well. (Considine, when looking at a Kefauver brochure from the Minnesota campaign, noticed the same thing.)

To really consecrate a particular slogan, you need to hammer it home repeatedly. Kefauver’s insistence on juggling multiple slogans made it that much less likely that he’d be remembered for any specific one.

Postscript: More Than Words

When Kefauver died in 1963, Time magazine did mention his use of the phrase “an even break for the average man,” implying (with their typical obnoxiousness) that it was an empty and meaningless platitude.

That was false. Speaking to Considine during the ’56 campaign, Kefauver explained in detail how the slogan translated into policies on topics as varied as foreign policy, civil rights, and farm price supports.

Kefauver understood contemporary America – especially economically – to be stacked against the average person in favor of big corporations. Whether Time agreed or not, the idea of “an even break for the average man” had real meaning to him. He saw his role as fighting to make America more fair for the little guy against systems that were rigged to favor the rich and powerful.

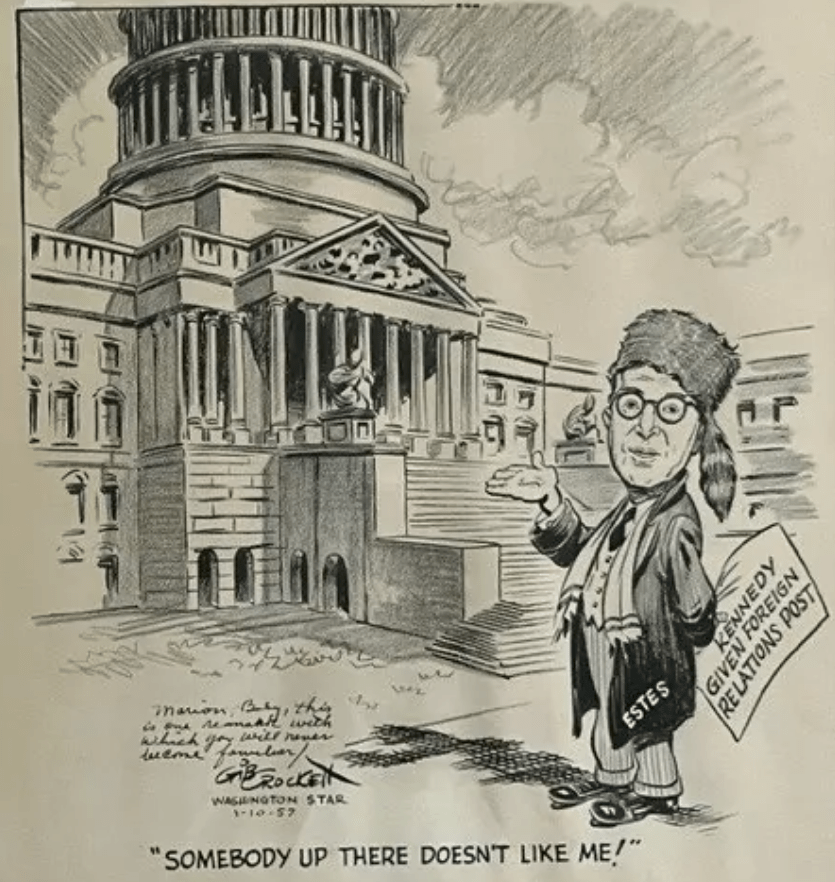

But I think his quest for an “even break” in 1956 was also personal. He was fighting for his own fair shot at the nomination as much as anything.

In 1952, he won virtually every primary that he entered, demonstrating broad popularity with Democratic voters. That didn’t stop party leaders from tossing him aside at the convention in favor of Stevenson, who did not enter a single primary and practically had to be dragged kicking and screaming into accepting the nomination.

In 1956, a similar tone hung over a lot of the campaign coverage. It was generally understood that Kefauver would need to run the table – or close to it – to have a shot at winning. Even then, he might be snubbed at the convention yet again. Meanwhile, as long as Stevenson didn’t lose all of the primaries, he was still viable. And if he failed, there was always an Averell Harriman or a Soapy Williams or an LBJ waiting in line to snatch the crown.

In his September speech in Harrisburg, Kefauver used an analogy to explain the differing attitude of Democrats and Republicans when it came to the people.

He recalled that when Andrew Jackson was inaugurated as President, he threw open the doors of the White House and said, “Let the people in.”

Kefauver said that Jackson’s choice “was more than an expression of warm-hearted Tennessee hospitality. It symbolized the Democratic faith that animates the Democratic party today.”

On the other hand, Kefauver said that Eisenhower and the Republicans ran the White House “as if it were a split-level rambler. During election seasons, they let the voters in on the lower level. Between election seasons, however, they hang a sign on the door reading: ‘Please do not disturb.’ And on the upper level, the preferred citizens, the men of wealth and the great corporate managers, confer and decide in great splendor.”

It was a clever campaign analogy. But I can’t help but wonder if Kefauver viewed his own quest for the Presidency in similar terms.

The Democratic Party was more than willing to use Kefauver’s brilliant connection with the voters to boost other candidates. But when he sought the White House for himself, he found the doors locked and the “Please do not disturb” sign hung on the knob, while party bosses decided the nominee without him.

After running himself ragged campaigning for the Democratic Party that he loved, it surely broke Kefauver’s heart to realize that party leaders didn’t love him back. The poor guy never could catch an even break.

Leave a comment