Social media has changed our politics in numerous ways. Among them, it has allowed for instant reaction to events, even as they’re unfolding. Even while a debate or a speech is still going on, you’ll see dueling partisans seeking to spin things in their favor, or fact-check exaggerations or misstatements in real time.

You’re likely aware that the concept of political campaign rapid-response teams dates back before the age of social media. But you may not know that the idea was first pioneered all the way back to the 1950s.

This is the story of the “GOP Truth Squad.”

When Harry Gives ‘Em Hell, Republicans Plot Revenge

In 1948, Harry Truman stunned the press – and the Republicans – by winning a re-election that few thought he could. He famously barnstormed the country on his whistlestop tours, “giving ‘em hell” and amping up Democratic enthusiasm all over the country.

The GOP evidently looked at Truman’s surprise success and concluded that it wasn’t due to his courage, or his charisma, or his oratorical skill. They believed he’d won by lying about Republicans and their record.

South Dakota Senator Karl Mundt came up with an idea: What if we had a group of Republicans following Truman around, speaking after he spoke, and basically delivering a rebuttal? What if the GOP could counter Truman’s exaggerations and lies right there on the spot? And so, the “GOP Truth Squad” was born.

Republicans first deployed the “Truth Squad” during the 1952 campaign, following Truman around as he campaigned for Adlai Stevenson. They drew a bit of attention, haranguing the outgoing President for supposed misstatements, but they weren’t a major factor in the campaign.

Rather than deciding that the bit had failed, Republicans concluded that they just hadn’t gone big enough. Next time, they’d take things to the next level – and to the skies.

A Sophisticated Operation

For the 1956 election, the GOP chartered a fleet of planes, which they slathered with a red-white-and-blue paint scheme with the words “GOP TRUTH SQUAD” emblazoned on the side. The planes were staffed by a rotating cast of Senators, Congressmen, and Cabinet officials. In the words of the squad’s PR director, Gil Violante, “We’re not a glamour deal, but a group of hard working guys dedicated to getting the truth to the people.”

Their job was to fly into towns where Stevenson or Kefauver had just spoken – typically about a half hour after the Democrats had left – and offer statements to reporters calling out alleged misstatements, exaggerations, or screw-ups made by the opposing ticket. As Violante said, their goal was “getting the last word.”

What fascinated reporters the most was the way that the “Truth Squad” had their talking points – responding to specific statements made by the Democratic candidates – all ready to go as soon as their plane touched down. How could they respond so quickly, when they hadn’t even been present for the speech?

The logistics behind the “Truth Squad” were pretty impressive, especially for 1956. The planes were equipped with televisions, allowing the squad members to watch the speech live. (If the speech wasn’t televised, they’d send an operative to the press room to swipe an advance copy of the speech.)

When a squad member heard or read a statement that required rebuttal, he’d call the “answer desk” in Washington, where a staff led by Eisenhower economic advisor Gabriel Hauge would do some quick research and call back within five minutes with relevant facts, statistics, and quotes.

It was a highly effective gimmick, and it generally ensured that any story about a speech given by Stevenson or Kefauver would contain the GOP counterpunch. Sometimes, the story about the Democratic speech would run side-by-side with a piece on the “Truth Squad’s” response.

An Auspicious Beginning

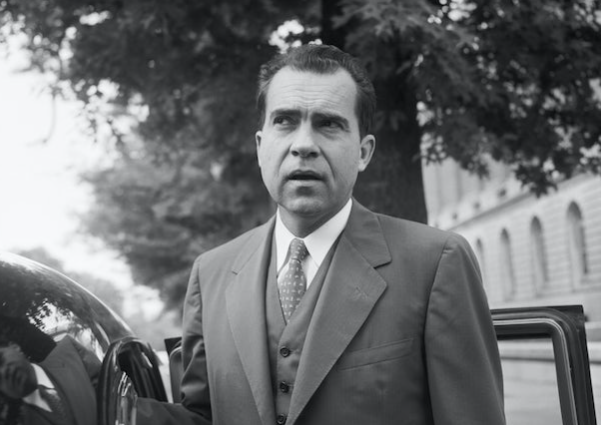

The 1956 version of “Truth Squad” was officially commissioned on September 18th, with a ham-and-egg breakfast at Washington’s National Airport at which both President Eisenhower and Vice President Nixon spoke.

Eisenhower’s speech, as usual, was full of pious sentiments. “I see no reason for going to the public with anything except the truth,” the President told the squad. “By no means do we need to claim perfection. We don’t need to indulge in the exaggerations of partisan political talk.”

After a brief case for his administration’s record on foreign policy and the economy, Ike said, “With all the facts of our economy, with all the facts of the world scene, you can go before the American public. And again I say: tell the truth, tell it forcefully. And that should be our campaign… As long as we have a positive plan of our own and are carrying it forward, let them do the yelling.”

Nixon, who had a better grasp of politics than his boss, offered more pragmatic advice. He told the squad to “look at the record… We don’t have to whitewash it with clever quips or fancy phrases. Plain talk will do the job.”

Initially, the “Truth Squad” started following Kefauver, presumably on the theory that his notorious history of public-speaking stumbles would give them plenty to criticize.

For his part, Kefauver appeared to welcome the challenge. He told a crowd in Moorhead, Minnesota, that the squad “will be out your way soon. I suppose they will because these truth squad, or ‘myth men’ as I prefer to call them, have as their assignment to follow Adlai Stevenson and me around and try to futz up the truth we tell you.” He challenged the squad to “tell the truth about a few things,” like the administration’s lack of support for farm price supports or their preference for tax cuts for corporations instead of “for the Joe Smiths of America.”

But the “Truth Squad” quickly got its revenge. During his Minnesota swing, Kefauver claimed that Ancher Nelson – the Republican candidate for governor who had previously headed the Rural Electrification Administration – had supported increases the interest rate on REA loans. The squad quickly discovered that Nelson had in fact vigorously opposed said interest hikes.

In response, Kefauver apologized to Nelson at his next stop. “If I did [Nelson] an injustice,” Kefauver said, “I am sorry.”

The “Truth Squad took the opportunity to spike the football. After a brief blast of Red-baiting – implying that Kefauver was soft on Communism because of his votes against establishing and funding the House Un-American Activities Committee – the squad announced that henceforth, they would follow Stevenson around instead.

Senator Frank Billings of Wyoming, one of the “Truth Squad,” said that they were abandoning Kefauver because “we think we should turn our attention to more important people.”

The squad also implied that they’d already heard everything Kefauver had to say. “Keef’s wearing out his needle playing the same old record,” sneered Rep. Donald Jackson of California.

“Truth Squad” Goes Madly After Adlai

From that point on, the “Truth Squad” dutifully pursued Stevenson around the country, racking up over 20,000 miles visiting 83 different cities in 35 states.

“Who can blame Adlai Stevenson if he occasionally pauses in mid-speech and glances skyward as though he were being watched?” wrote Bill Broom of the Duluth News-Tribune. “As a matter of plain fact, he is. In a campaign chock full of electronic surprises… the Republican party has developed another new gimmick, aerial eavesdropping.”

The “Truth Squad” managed a couple dings on Stevenson. They jumped on a statement he made in St. Louis that “Soviet planners intend to pull level with America by 1965 and ahead by 1970” in production of resources such as steel, petroleum, and electricity. The squad accused Stevenson of swallowing Soviet propaganda and said, “Selling America short in this wicked world is too dangerous a tactic to be used as a political device in a Presidential campaign.”

The squad also pounced when the Democratic candidate accused the administration of “appeasing” the Peron regime in Argentina with a $100 million fact. In fact, they countered, Eisenhower had given no loans to Peron whatsoever, while Truman had provided loans totalling $130 million. They demanded an apology. (Unlike Kefauver, Stevenson declined to offer one.)

As time wore on, the “Truth Squad” faced an unexpected problem: Stevenson didn’t give them much material to work with. By the squad’s own accounting, they uncovered only 21 Stevenson statements that, in their view, required correction. By way of comparison, the “Truth Squad” following Truman around in ’52 uncovered over 200 such statements. Even Mundt admitted that Stevenson was in the “minor leagues” when it came to misstatements.

Did the squad respond by folding its tent and going home? Of course not! Instead, they found much pettier things to complain about.

For instance, when speaking on the campus at Yale, Stevenson briefly appeared to forget the name of Connecticut Governor Abraham Ribicoff. The squad claimed this was because “he only knows millionaire governors like [Averell] Harriman and Soapy Williams.”

The following week in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, Stevenson wrapped his speech by saying, “On leaving here, I shall go to Pittsburgh, where I shall have something to say.” Smirked Jackson in response, “It’s about time.”

For his part, Stevenson responded to the “Truth Squad” with a mixture of wry amusement and annoyance. When the squad was first unveiled, Stevenson told his staff that “he thought it significant that the Republicans could make front-page headlines by promising to tell the truth.”

On another occasion, he spotted the “Truth Squad” plane in the sky while he was speaking. “Well, wouldn’t you know it,” he remarked. “That’s the Republican truth squad. I don’t know what connection they have with the truth. They will try to answer what I said before they know what I said.”

Other times, he showed flashes of irritation. While speaking to a United Steelworkers gathering, he fumed, “I get pretty disgusted, frankly, hearing the Republican campaign orators claim credit every time they face a labor audience for increasing the minimum wage to $1 [per hour]. That increase was made possible by a Democratic congress which pushed it through over the expressed objections of the President.”

Other Democrats pointed out that the “Truth Squad” often seemed to be… well, less than truthful. After the squad blew threw Montana on Kefauver’s trail, state Democratic chair Leif Erickson recalled Eisenhower’s admonition to avoid exaggerations and distortions. “I can understand why such a warning from deemed necessary,” Erickson noted, “but either this particular ‘truth squad’ was absent or they figured the President was talking with his tongue in his cheek.”

“To give the devil his due, this ‘truth squad’ has courage,” Erickson added. “It would take courage to come to Montana and tell our farmers this Administration has been good for them.”

The squad’s reliance on precision timing – showing up right after Stevenson’s departures – occasionally led to trouble. On a couple of occasions, the “Truth Squad” touched down while Stevenson was still speaking.

Toward the end of the campaign, the squad’s flight to Pittsburgh was delayed by bad weather. They landed and rushed to their hotel to watch Stevenson on the TV… only to find that the Democrat was also late, and therefore missed the televised window. (They hadn’t bothered to send anyone to the venue to catch the speech in person.)

Was It A Campaign Revolution… or Air Cover for the General?

Did the “Truth Squad” make a real difference in the end? Given what a rout the election was, it’s hard to call them the deciding factor.

In the heat of the campaign, the squad itself seemed uncertain of its impact. “Even the ‘truth squad’ members have no idea whether their frenetic efforts are winning any votes for the Republicans,” wrote Ruth Montgomery of the INS.

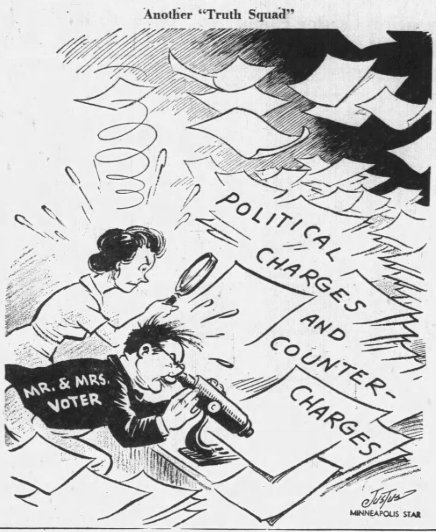

The squad’s efforts were an early example of what we now call “flooding the zone,” airing a flurry of counter-charges to Democratic talking points that left voters unsure what to believe.

Jackson suggested that the squad’s primary contribution was the “morale factor.” As Montgomery wrote, “By following closely on the heels of a Stevenson or Kefauver rally, the GOP squad can reassure frightened local Republican workers that their own party is still in there pitching.”

That last remark hints at what may have been the “Truth Squad’s” most important function.

Eisenhower basically sat out the 1956 campaign. According to his advisors, he was so confident of victory that he felt no need to hit the trail. But it’s important to remember that his health was a concern.

The previous fall, Ike had suffered a heart attack severe enough that it called into question whether he could run for a second term. In the summer of ’56, he had an operation to remove a bowel obstruction, a procedure that left him hospitalized for three weeks. It’s not clear that Eisenhower could have withstood the grind of the campaign trail even if he’d wanted to (which he absolutely did not).

Nixon faithfully stumped around the country on the administration’s behalf, but he was a controversial figure. (The Democrats tried to make an issue of the fact that if Eisenhower died in office, Nixon would become President.)

By sending the “Truth Squad” out to supplement Nixon’s efforts, the GOP ensured that reporters would write about them – instead of writing about why the President wasn’t campaigning.

Whatever else they accomplished, the “Truth Squad” succeeded in annoying Democratic campaigners. A couple days after the election, then-Senator John F. Kennedy gave a humorous speech at Boston’s Tavern Club about life on the campaign trail.

“I hope, when I am relaxing on the beaches of Cape Cod or Palm Beach,” Kennedy told the audience, “that I will be able to utter some mild statement about the weather or the Harvard Team without nervously peering over my shoulder to see if Leverett Saltonstall and the Republican truth squad are still refuting my every statement.”

Leave a comment