I purchased my first political button when I was about 13. The lady who lived down the street was moving, and she held a yard sale to clear out the bric-a-brac she didn’t feel like packing and shipping to her new home.

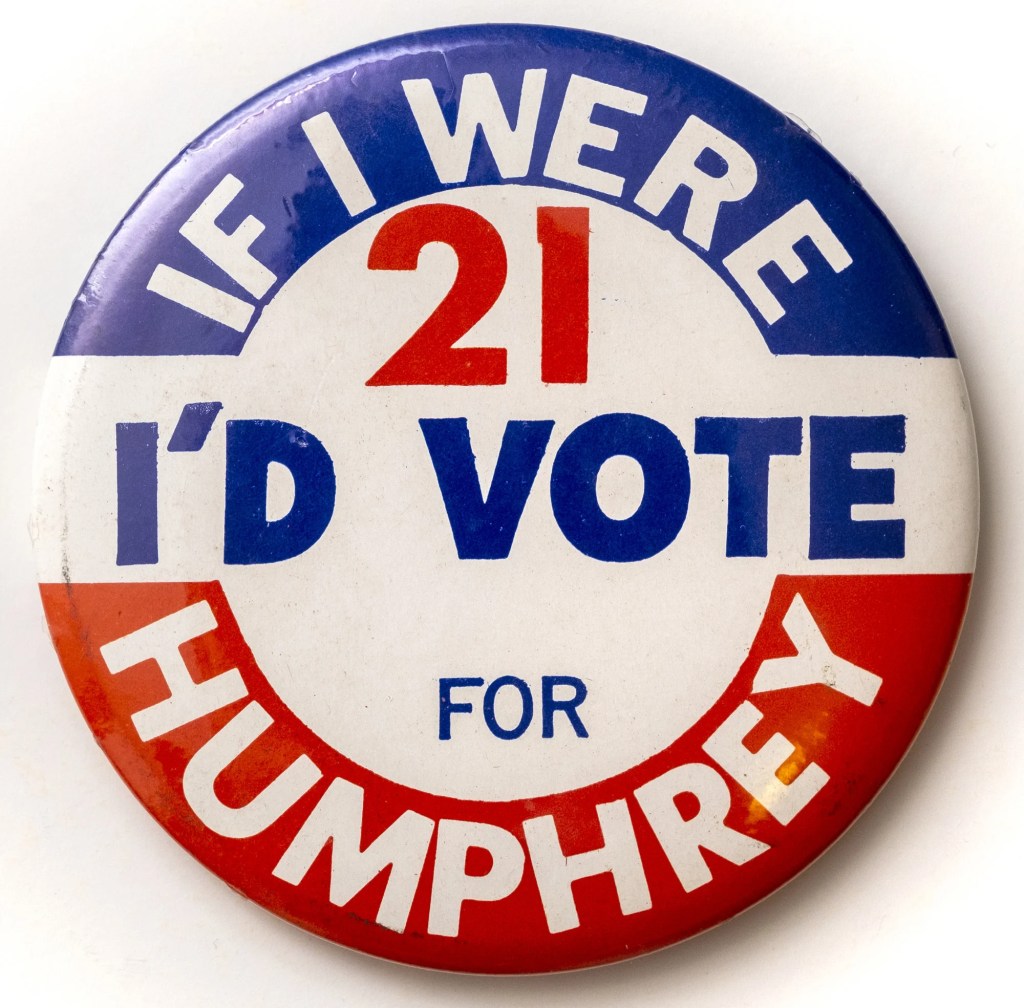

One of the items I purchased was a 3-inch red-white-and-blue slogan with the slogan, “IF I WERE 21 I’D VOTE FOR HUMPHREY.” I knew who Hubert Humphrey was, but the first part of the slogan threw me a bit. Why 21? Didn’t you only have to be 18 in order to vote?

Of course, the answer is that you had to be 21 to vote in 1968, at least in most states. The 26th Amendment to the Constitution, which lowered the voting age to 18, wasn’t ratified until 1971.

As with the 25th Amendment, which covered the question of succession when the President was too ill to perform his duties, credit for the 26th Amendment typically goes to Birch Bayh, who was chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments at the time the amendment was ratified. But as with the 25th, what Bayh really did was finish the work that Estes Kefauver – among others – started.

The Quest Begins in WWII

Kefauver first became involved with the voting-age question while he was still in the House. In 1943, Georgia Governor Ellis Arnall lowered the voting age in his state to 18, arguing that it was a fitting reward for the 18-year-olds who had fought for their country in World War II. Around the same time, Rep. Jennings Randolph of West Virginia proposed a Constitutional amendment to do the same thing nationally.

The bill went to the House Judiciary Subcommittee charged with reviewing amendments, which was chaired by New York Rep. Emmanuel Celler. The hearings were largely ignored; according to Randolph, the hearing was attended by only eleven people (including the members of the subcommittee), and no reporters bothered to attend.

In spite of the apparent disinterest in the issue, Arnall and Randolph made an eloquent case for the amendment. “No one can convince me,” said the Georgia governor, “that a young man or young woman of 18 today does not have a power of understanding that transcends that of a 21-year-old man or woman of a generation ago.”

Rep. Kefauver, like his colleagues on the subcommittee, seemed rather skeptical of the proposal. In particular, he pushed back against Arnall’s idea of connecting the voting age to military service.

“[I]sn’t the strongest argument,” Kefauver said, “that boys and girls ordinarily finish high school when about 18 years of age, and at that time civics, political science, and matters of responsibility in government are very much in their minds, and if they don’t exercise those responsibilities immediately, in the 3 years they may lose interest?”

That idea would stick with Kefauver, and he would frequently trot it out in the years to come in support of the idea.

A False Start in the Fifties

After World War II ended, the voting-age question went onto the back burner for a while. But Kefauver brought it up again during his 1952 campaign for President. Supporting a lower voting age was consistent with one of the themes of his campaign, which was giving more political power to young people.

While speaking at the University of Miami at a campaign stop that April, Kefauver endorsed the idea of lowering the voting age, becoming the first Presidential candidate to do so. (Adlai Stevenson would also endorse the idea later on.)

Speaking on the radio in New York in June, Kefauver expounded on his support for a lower voting age, saying that 18-year-olds of the present day “are better qualified to vote today than I was at the age of 21,” because they had more and easier access to political information thanks to radio and TV. He argued that keeping the voting age at 21 risked “dampening [young people’s] intelligent interest in government.”

Although Kefauver’s bid for the Presidency fell short, the man who made it to the White House shared his interest in youth voting. During his State of the Union address in January 1954, President Eisenhower called for the voting age to be lowered to 18.

Like Arnall and Randolph before him, Ike invoked military service as the justification. “For years our citizens between the ages of 18 and 21 have, in time of peril, been summoned to fight for America,” Eisenhower said. “They should participate in the political process that produces this fateful summons.”

Within hours of Eisenhower’s address, Kefauver and a bipartisan group of seven senators drafted a bill calling for an amendment lowering the voting age to 18. By the beginning of March, Kefauver’s subcommittee on Constitutional amendments reported out a similar bill sponsored by Bill Langer of North Dakota; by Mach 15, the Judiciary Committee had voted to send the bill to the full Senate.

Conditions looked favorable for passage of the amendment. A Gallup poll that spring showed that 58% of adults favored the concept of lowering the voting age. The idea was even more popular among the would-be new voters; people between 18 and 20 favored the idea by a margin of nearly 2-to-1.

For fun, Gallup also assembled a quiz of political knowledge and gave it to a random sample of respondents. They found that 18-to-20-year-olds scored better on the quiz than their elders did.

When the bill came up for debate in the Senate on May 21, however, it failed to pass. The 34-24 vote in favor was well short of the two-thirds majority needed.

The bill’s failure was largely pinned on Majority Leader William Knowland. Critics alleged that Knowland, either due to incompetence or a grudge against Langer, unwisely chose to bring the bill forward on a Friday afternoon the week before Memorial Day, when a lot of Senators had already left town.

Although Knowland was hardly a genius floor leader, this criticism was unfair. Knowland was part of Kefauver’s bipartisan group of Senators who proposed the amendment after Ike’s State of the Union. He wanted the bill.

The fact is that both Democrats and Republicans had been responsible for the delays on the amendment vote. And in a coincidence of poor timing, the Supreme handed down its ruling on Brown v. Board of Education just four days earlier, pissing off some Southern Senators who had previously been open to the amendment.

Besides all of that, even if the Senate had passed the amendment, it would never have made it out of the house for one simple reason: Celler.

He and Kefauver were like-minded politically in a lot of ways, but they disagreed strongly on the voting age. Celler was firmly convinced that teenagers weren’t mature enough to vote responsibly. As chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, he had the ability to block any amendments lowering the voting age, and he did so. Repeatedly.

A New Frontier, But No Youth Voting

When John F. Kennedy entered the White House on a wave of youthful energy, the idea of lowering the voting age came up again. This was somewhat ironic, as Kennedy himself was cool to the idea. He’d voted against the 1954 amendment to lower the voting age, and he did not consider it a political priority to expand the vote to younger Americans.

Nonetheless, Kefauver came right out of the chute in 1961 with an amendment to set the voting age at 18. He was in good company; four other Senators made similar proposals, including Jennings Randolph (still championing the same cause he’d pushed since 1943).

The proposal – along with a slew of other proposed reforms to the electoral system, including abolition of the electoral college and outlawing poll taxes – wound up in Kefauver’s amendments subcommittee, and he held hearings on the lot of them in June.

On behalf of the Kennedy administration, Assistant Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach testified that Kennedy was against a national move to lower the voting age, believing the decision should be left to the states.

Among those in favor of the bill was Leo Savage, a student at Ohio’s Findlay College, who testified before the subcommittee. Kefauver made a point of noting that Savage had traveled to Washington at his own expense to testify.

Savage testified that many of his 18-year-old classmates were excited about politics, and were frustrated at having to wait until 21 before they could vote. When Kefauver asked whether “young people are taking an interest in and working in political campaigns more than they used to,” Savage enthusiastically agreed: “They definitely took part in the last election, and they were very much interested in the last presidential election as well as many congressional elections. The youth of this Nation have been deeply interested in the outcome.”

In the end, without the administration’s support, the voting-age amendment died in the subcommittee.

After the 23rd Amendment gave DC the right to vote in federal elections, Kennedy urged that the voting age be set at 18. (This would not need to go through Celler’s Judiciary Committee, thus avoiding his certain veto.) The tireless Randolph, backed by Kefauver, urged the move, pointing out that the citizens of the nation’s capital “already bear the responsibilities of citizenship without its privileges.”

The Senate DC subcommittee voted in favor of setting the capital’s voting age at 18. But when the proposal reached the Senate floor and Russell Long of Louisiana moved an amendment to change it to 21, the Kennedy administration didn’t lift a finger to stop it.

Postscript: Randolph Gets It Done At Last

Kefauver’s death robbed the Senate of one of its strongest champions of young voters. But Jennings Randolph – God bless him – never gave up the fight.

He tried to get LBJ to add the proposal to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as a way of bypassing Celler, but LBJ balked. He sponsored an amendment to the VRA in 1970 lowering the voting age to 18 in both national and state elections. When the Supreme Court ruled that Congress didn’t have the power to set voting ages in state elections, he sponsored the bill that ultimately became the 26th Amendment. It was the eleventh time Randolph had sponsored such an amendment, and it finally worked out.

The first registered 18-year-old voter after the amendment’s ratification was a young woman in Elkins, West Virginia named Ella Mae Thompson Haddix. The 71-year-old Randolph personally escorted her to the courthouse to register. It was a fitting tribute to his decades of effort.

I like to think that Kefauver was there in spirit, as well. He didn’t live to see the final victory, but I’m sure he was up there somewhere, grinning his half-moon grin.

Leave a comment