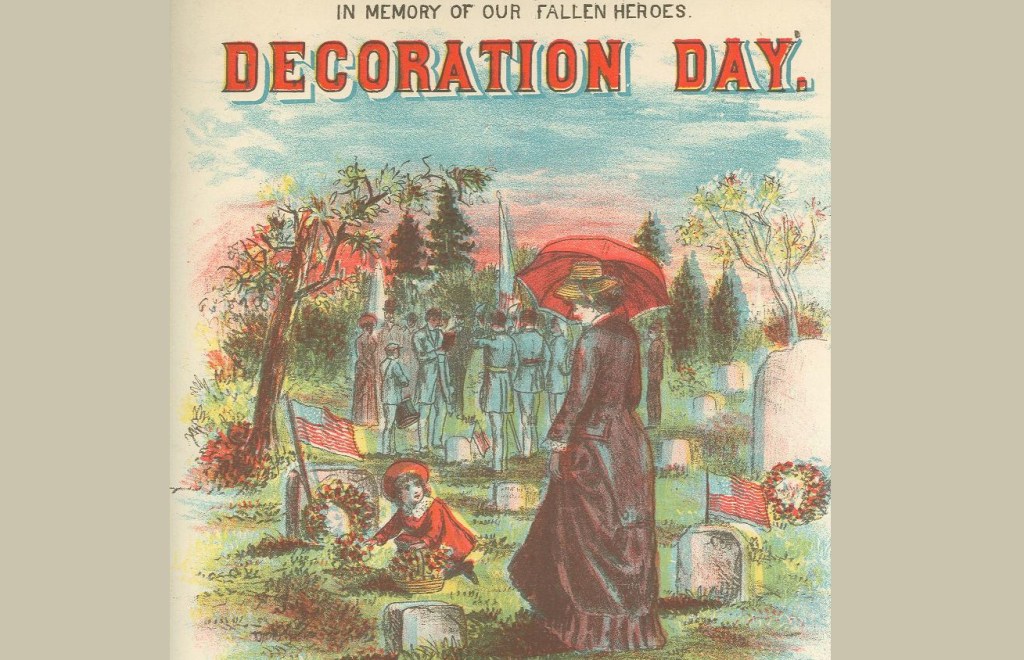

Today is Memorial Day in America. The holiday was originally designated as to remember and honor the soldiers who lost their lives in the Civil War. (It was originally known as “Decoration Day,” because one of the primary activities on the day was to leave flowers on the graves of the deceased soldiers.)

For most Americans, though, Memorial Day is considered the unofficial start of summer. Instead of leaving flowers on veterans’ graves, we’re more apt to celebrate the day with picnics, barbecues, and trips to the beach.

These activities – particularly the beach trips – are facilitated by the fact that Memorial Day always occurs on the last Monday in May. Americans love to get away on a three-day weekend, and the fact that Memorial Day occurs at a time when temperatures are warming up makes it ideal for outdoor-themed getaways.

What those vacationing Americans may not know, however, is that it wasn’t always this way. Memorial Day used to be celebrated every May 30th, regardless of what day of the week it fell.

How it came to be celebrated on Monday is an interesting story – and one in which Estes Kefauver plays a role. So what better way to celebrate the day than to tell the story?

Like most things surrounding the Civil War, Memorial Day was controversial from the beginning. It first became a national holiday in 1868, just three years after the end of the war. However, Decoration Day was originally proclaimed as a day to honor the Union (aka Northern) dead. The Northern states dutifully began recognizing the day; by 1890, all of the Northern states celebrated it.

The Southern states, meanwhile, were a different story. Generally, they designated their own Decoration Days (mostly in the spring, sometime between April and June) to honor the Confederate dead. (Many Southerners claim that their Decoration Days came first, and that the North stole the idea from them. I’m not about to try to referee that dispute.)

For years thereafter, Decoration Day was one of the many low-key conflicts between North and South. I’d argue that the first “Cold War” in America had nothing to do with the Soviets, but was in fact the smoldering hostility between the sections that persisted through the 50 years or so after the Civil War.

It wasn’t until the 1910s, with World War I looming in the background, that both sides agreed to bury the hatchet and celebrate Memorial Day on the same day. Thanks to the ensuing World Wars, Memorial Day evolved into a day for remembering deceased soldiers generally, not just those who fought in the Civil War.

By the middle of the 20th century, Americans’ perspective on Memorial Day – and holidays in general – had shifted again. The rise of the highway system and widespread car ownership made out-of-town travel increasingly feasible. This was boosted by attractions (such as Disneyland, which opened in 1955) that gave people a place to travel to.

Unsurprisingly, the push to move holidays to Monday began with groups affiliated with travel. But by the early 1960s, retail and manufacturing interests were also on board, including the National Association of Shoe Chain Stores, the American Retail Federation, and the National Shoe Manufacturers Association.

Many of them had surveyed their workers and found that three-day weekends were highly popular. Some of them also figured that moving holidays to Mondays (typically a slow day for retailers anyhow) would reduce absenteeism, since a number of workers treated Tuesday or Thursday holidays as a chance for a four-day weekend. (Take a look around your workplace on the day after Thanksgiving, and you’ll see my point.)

One of the big boosters for moving Memorial Day to Monday was W. Maxey Jarman, chairman of the board of Genesco, a shoe company based in Nashville and one of Tennessee’s largest employers. In early 1963, Jarman wrote a letter to the state’s congressional delegation asking them to support moving Memorial Day to Monday.

Kefauver introduced a bill doing just that in March 1963. He made no secret of the fact that the main point of the change was to create a three-day weekend. “If Memorial Day were to fall on a Monday each year, our people could count on a long weekend for relaxation and spiritual refreshment,” Kefauver said in his speech introducing the bill. “This would· work to the benefit not only of those millions of workers in offices and factories but also of their employers in scheduling their work.”

However, Kefauver also suggested a nobler purpose for the change. “I believe that more of our people would observe Memorial Day as a holiday and consequently pause to reflect upon the real meaning and purpose of this day,” he said. In Kefauver’s mind, that purpose was to express gratitude that the country was no longer at war with itself, and to express “our gratitude to those departed for their supreme contribution to the preservation of freedom.”

Kefauver’s proposed change didn’t sit well with everyone. Mrs. M.K. Lewis, in a letter to the Nashville Tennessean, “We are living in an era when change of some sort seems to be expected daily. Next comes a suggestion from Mr. Estes Kefauver… that Memorial Day should be changed because people do not have time to take a trip if it does not fall on Monday. We know the wonderful expressways are being built to be used even if we have to change holidays to induce people to take trips.”

If Memorial Day could be moved, asked Mrs. Lewis, “what about July 4, Christmas and New Year’s Day? These have a habit of falling on any old day which cuts people out of a long weekend trip.” She concluded that “if they get Memorial Day changed they will be after all the rest and every holiday will be on Monday no matter what the occasion.”

Mrs. Lewis was probably unaware, but there was an effort afoot to do what she (sarcastically) suggested. Representative Samuel Stratton of New York filed a bill around the same time as Kefauver’s that would have moved Washington’s Birthday, Memorial Day, Independence Day, and Veterans Day to Mondays.

Stratton’s bill – like Kefauver’s – didn’t get anywhere. But in 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, which moved three of the four holidays that Stratton proposed (Independence Day was spared) and made Columbus Day a federal holiday, also to be celebrated on Monday. (In 1978, Congress moved Veterans Day back to November 11th after complaints from veterans’ groups).

The long weekend associated with Memorial Day has proved immensely popular, as Maxey and Kefauver predicted it would. Kefauver’s other prediction, that moving the holiday would lead Americans to “reflect upon the real meaning and purpose of this day,” sadly proved inaccurate.

But rather than end on a downbeat note, I’ll tip my hat (and my hot dog) to Kefauver, Jarman, Stratton, and all the others who helped make this day what it is today. After all, what could be more American than a three-day weekend?

Leave a comment