When Estes Kefauver ran for President in 1952, he carried with him a larger-than-life reputation as a mythic gang-buster from his televised Senate hearings into organized crime. To a lot of his supporters, he wasn’t just a young and promising politician… he was a national hero. It was this heroic reputation that led Time magazine to skewer Kefauver was “a sort of Senator Legend – half man, half fiction, a candidate conjured up by the disillusioned… Democrat to answer his own yearnings.”

The Senator’s mythic stature was captured well by an article published in U.S. News and World Report in late February of ’52, after Kefauver had begun his campaign but before his upset victory over President Truman in New Hampshire and his largely victorious run through the primaries.

The article attempted to provide a preview of how a President Kefauver might operate his administration. It painted a rather flattering picture, but it also underscored the degree to which Kefauver was still a hazy figure in the public mind, arguably more of a symbol of integrity and good government than a flesh-and-blood person.

The article took for granted that a Kefauver administration would largely continue the policies of the Truman and Roosevelt administrations. This was a reasonable supposition, as Kefauver had faithfully supported FDR’s New Deal and Truman’s Fair Deal as a member of Congress. Also, as a Presidential candidate, he repeatedly insisted that he had no major policy differences with the administration.

As a result, the article is full of sentences like this:

- “No startling new program would be thrown at the country by Kefauver.”

- “Taxes would remain about as they are now.”

- “In foreign policy, Kefauver would go along with the broad outlines of past policies.”

- “Mr. Kefauver would go along with the present social program.”

- “Kefauver would be inclined to cruise so far as policies were concerned.”

That last one, in particular, is utter nonsense. Kefauver had distinct interests of his own – antitrust and monopoly, civil liberties, political process reform – and he surely would have pursued them in the White House. He wasn’t emphasizing those issues on the trail, but that doesn’t mean he would have ignored them. The idea that he would “be inclined to cruise” in office is ridiculous. Clearly, whoever wrote this article had little familiarity with Kefauver’s record in Congress.

Take a moment and read the draft text of the acceptance speech Kefauver would have given if he’d received the nomination in 1952. Is this the rhetoric of a man who’s “inclined to cruise”? I think not.

Anyhow, if we accept the premise that Kefauver would pursue basically the same policies Truman had, then what’s the case for Kefauver? Why not just give Truman another term?

Well, that’s where the mythical part comes in. Kefauver might continue the policies of his predecessors, but he would nonetheless represent a revolutionary departure from the status quo. As the article sums it up, “It will be a different Democratic Party if he wins.”

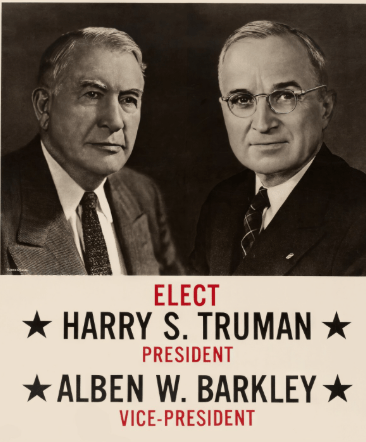

In what ways would the Democratic Party be different? For one thing, the article pointed it, Kefauver would represent a generational change in leadership. Much like today, the Democratic Party of the early 1950s was run by a bunch of old guys. Truman was 68, and VP Alben Barkley was 74. “In Congress, many committee chairmen are over 70; several are over 80.” By contrast, Kefauver turned 49 that summer.

“A Democratic Party hierarchy, grown old in office, would give way to relative youth,” the article suggested of a Kefauver victory.

Not only would Kefauver bring in a younger cohort of leaders, U.S. News posited, but he’d bring in a cohort with different priorities than the existing Dem power brokers. “The political base of the Democratic Administration would be changed radically,” the article suggested.

The Kefauver administration would “make a clean sweep of the hangers-on who are so present about the White House now” and would freeze out “[b]ig-city machines that have been so powerful in the past.” In their place, Kefauver would elevate “the ‘clean government’ groups,” as well as “young men with new ideas.” (How these “young men with new ideas” would square with the presumption that Kefauver would cruise on existing policies, the article leaves unexplored.)

And this new Democratic Party would be inspired by its new leader. It’s at this point that the article veers into straight-up hagiography.

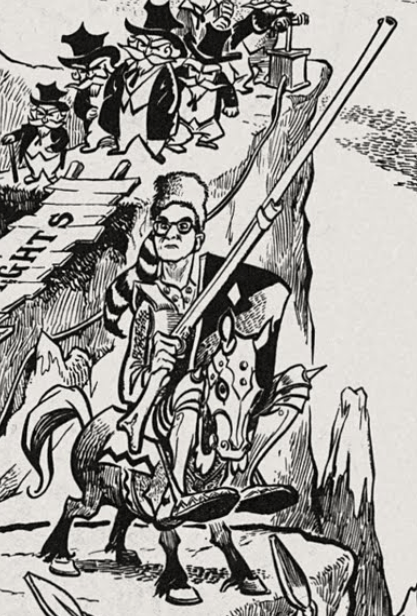

“Mr. Kefauver is the white knight in a coonskin cap who won his spurs by defeating Boss Edward H. Crump and the Memphis political machine,” the article gushes. “He is the exponent of law enforcement who fought the nation’s crime syndicates.” Henry Luce would gag on this kind of fanboy language, and he wouldn’t be totally unjustified in doing so.

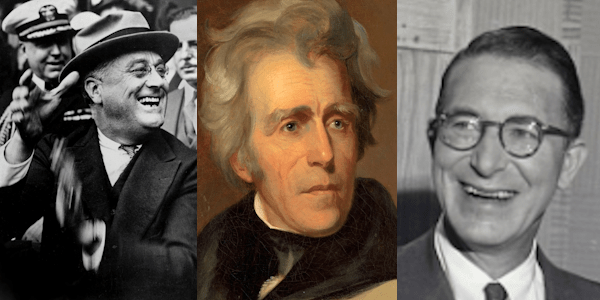

The article goes on to liken Kefauver to legendary Democratic Presidents of yore. “Estes Kefauver has some of the Roosevelt qualities in his make-up,” the article asserts, suggesting that “[j]ust as there was talk of Roosevelt luck, so is there talk of Kefauver luck.” (There’s a certain bitter irony; although Kefauver had indeed had a fairly charmed political career up to this point, that luck would largely abandon him thereafter.)

Physically, the articles notes, Kefauver was “the lanky, Tennessee border type, the tall man of the hills that was noted in Andrew Jackson’s day.”

A Democrat who bore the legacy of Andrew Jackson and FDR? The article made Kefauver sound like a candidate straight out of central casting… which is sort of the point.

Needless to say, the article paints a rather idealized view of Kefauver’s candidacy. But if you read between the lines, you can see some of the factors that ultimately foiled his bid. For instance, the fact that he simultaneously pitched himself as the natural heir to the Roosevelt-Truman legacy while also proclaiming himself the needed change from a corrupt administration was an uncomfortable straddle.

And of course, the big-city bosses and Truman Administration “hangers-on” who controlled the nomination weren’t about to give it to someone who wanted to throw them all out of power. (The article notes that Kefauver’s relative moderation on civil rights also made him anathema to old-line Southerners, the other Democratic power base at the time.)

All that said, I still believe the Democrats made a mistake in stiff-arming Kefauver’s bid for the nomination. After all, look at the GOP nominee. Dwight Eisenhower was a stiff, somewhat cranky old man who was largely uninterested in domestic issues. What made him such a formidable candidate was the mythology of Ike, the brave and brilliant general who won World War II. (That and the Madison Avenue ad campaign behind him.)

If the Democrats were going to beat a figure of Eisenhower’s stature, they needed a candidate with a sizable mythology of his own. Adlai Stevenson, the man who had to be dragged into running, was never going to be that candidate. Kefauver might have been.

But people and groups in power are generally loath to give it up, and when push comes to shove, they might rather lose an election than elevate someone who might take their power away. It would take eight years of GOP rule before Dems were willing to take a chance on a fresh face promising generational change.

Leave a comment