A couple weeks back, I shared an issue of Newsweek from October 1956 that reads like a dispatch from a future that never arrived; namely, a future where Adlai Stevenson ran considerably stronger against Dwight Eisenhower than he had four years earlier, and Kefauver’s popularity with farmers and factory workers was the primary reason. This would have set Kefauver up as a leading contender for 1960.

In reality, of course, Eisenhower won an even bigger landslide than he did in ’52. The landslide effectively crushed Kefauver’s hopes of national office, and he didn’t even run for the Presidency in 1960, opting instead for a third term in the Senate.

There was one state, however, that defied the overall trend of the ’56 election: Missouri. The Show-Me State was the only state that flipped from Eisenhower to Stevenson that year. It was particularly unusual to see this result from a state which was (then) famous as a presidential election bellwether. In fact, 1956 was the only election between 1904 and 2004 when Missouri backed the losing candidate.

And it wasn’t just a matter of Stevenson adding votes in existing Democratic strongholds. Of the 33 Missouri counties that Stevenson won in 1952, Eisenhower got more votes in two-thirds of those counties in ’56. Stevenson won the state largely by cutting into margin in Republican counties.

So what happened? Kefauver happened.

Stevenson’s running mate spent a lot of time in farm country, in precisely tin he sorts of places that the Democrats made gains in November. And around the time that Newsweek issue came out, Kefauver came to Missouri, stumping in GOP-friendly farm country… and drawing impressive crowds.

On October 17, Kefauver spent the morning in St. Joseph, Missouri, accompanied by Missouri Senator Thomas Hennings and gubernatorial candidate Jim Blair. The party then flew into Springfield, Missouri’s capital city. They arrived hours late – Kefauver was almost always late, spending extra time shaking hands and talking to voters at every stop – but were still greeted by a tremendous crowd. (Democratic county chairman W. Ray Daniel estimated the crowd at 2,500; Springfield’s Republican sheriff countered with an estimate of 500.)

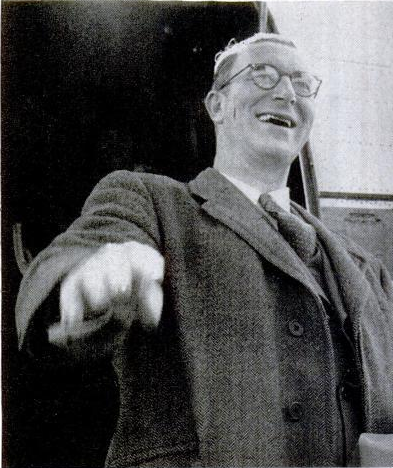

The crowd included the marching band from Parkview High School, which greeted Kefauver with “the inevitable ‘Tennessee Waltz,’” as the Springfield Leader and Press put it. Kefauver pasted on a smile as pretended to conduct the band for a moment before cheerfully welcoming the assembled crowd.

As he worked through the audience, Kefauver demonstrated why he was known as, in the words of the Leader and Press, “unquestionably [the Democrats’] No. 1 barnstormer and handshaker.” The city continued offering its adulation during a welcome parade through downtown Springfield that afternoon. Kefauver later said that Springfield gave him “one of the finest receptions we have received anywhere in the 37 or 38 states I have been.”

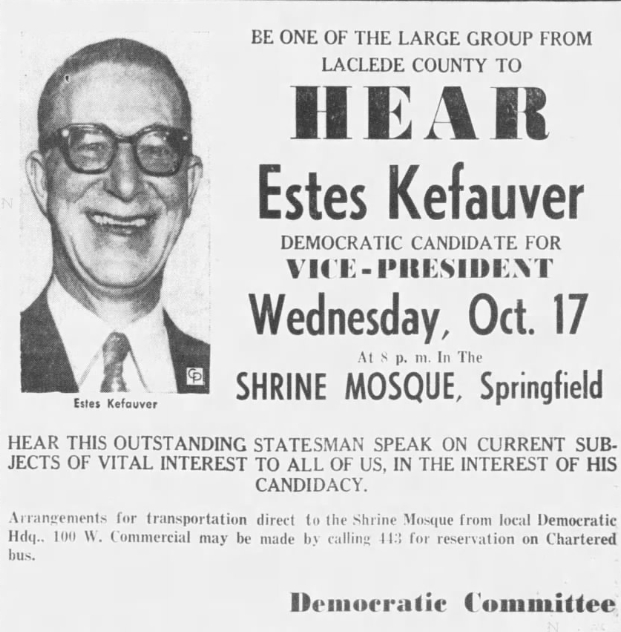

That evening, Kefauver spoke at the Shrine Mosque before a standing-room-only crowd of over 4,000 people. Not only did he reportedly outdraw Stevenson, who was speaking in Flint, Michigan on the same night, he drew the same size crowd that Vice President Richard Nixon did on his visit to Springfield three weeks before. Given Springfield’s Republican bent, it was an impressive crowd. Local observers said it was the largest gathering the city had ever seen for a Democratic candidate.

Kefauver was introduced by Charlie Brown, who was running for Missouri’s 7th District Congressional seat.

Brown introduced the Tennessean as the “noblest giant killer of them all.” Kefauver repaid the compliment, saying that Brown would make not only a fine Congressman, but a future VP: “After hearing him speak, he looks like he has the vitality and the ability to do it.”

Kefauver’s talk, which lasted about 40 minutes, offered a scathing critique of the Eisenhower administration, with a focus on foreign policy. Kefauver charged that the incumbent administration had made “not one move which would bring about a general peace in the world,” claiming that they were responsible for a “military race which could result in the annihilation of half the people on earth.”

Kefauver said that the Cold War arms race was no real peace, but “a condition of armistice – a condition under which both sides, armed to the teeth with the most wicked weapons within the conception of mankind, glare at each other across borders, ready at any minute to hurl death and destruction at each other.”

By contrast, Kefauver said that he and Stevenson “don’t want the threat of atomic war to be a permanent condition in the life of mankind; or the kind of America which must use two-thirds of its budget permanently for preparations for atomic warfare; or the draft to be a permanent part of life for American youth.” He said that the Democratic ticket had “the will to a permanent, lasting peace.”

He charged that the Eisenhower administration had forgotten all the promises he had made to voters in 1952. “I don’t think there’s an administration since U.S. Grant – certainly not since Teapot Dome – that there have been so many promises made to so many groups of American people… and then promptly forgotten.” (The reference to the Grant and Harding administration, both notorious for corruption and scandal, was no accident.)

Kefauver even tossed in a pop-culture reference, saying that the GOP’s campaigns were like listening to an Elvis Presley record. “’I Need You, I Want You, I Love You,’ they say before election,” Kefauver quipped. “Then you turn on the other side and it says, ‘You’re Nothin’ But a Hound Dog.’”

Despite the partisan nature of his remarks, Kefauver said, he bore no grudge against Republicans. “I like Republicans,” he said. “There is nothing about a Republican that a vote for a Democrat wouldn’t completely cure.”

He wound predicted a “smashing” Democratic victory in the election. “Victory is in the air,” he said. “We don’t have to concede a single state to the Republicans.”

After concluding his remarks, Kefauver stuck around for another 45 minutes, signing autographs and shaking still more hands. He and his campaign staff spent the night in a local hotel, heading out the next morning for a luncheon rally in Joplin, about 70 miles west of Springfield.

In Joplin, the VP candidate trained his fire on Eisenhower’s farm policies, claiming that the administration had worked “to force farm prices down and to push interest prices up,” selling out farmers for the benefit of “big banking interests.”

He said that money for farm price supports – which Agriculture Secretary Ezra Taft Benson infamously opposed – had been squeezed out of the federal budget due to rising interest payments on the debt. “The added cost of interest payments amounts to more, every year, than farm price supports cost in all 20 years under Democratic administrations.” Kefauver also claimed that 90-day loans now cost 10 times more than they had during World War II.

Kefauver’s visit to Missouri was just a couple of days, but his campaigning paid off. In the battleground 7th District, which included both Springfield and Joplin, Brown defeated incumbent Rep. Dewey Short, who had held the seat since 1934. Brown served for two terms before losing re-election in 1960. No Democrat has held the 7th District seat since.

Democrats had a good year statewide as well. Hennings cruised to re-election in the Senate. Blair won the governor’s race, and fellow Dem Edward Long was elected Lieutenant Governor. (Long would succeed Hennings in the Senate after the latter died in 1960.)

If Stevenson had won in 1956 – or at least run a competitive race – the results in Missouri likely would have been recognized at least partially as a tribute to Kefauver’s tireless campaigning and popularity with rural voters. But because Ike won in a landslide, the results in the Show-Me State were written off as an anomaly, a coin flip that came up tails instead of heads for no particular reason, just random chance.

Leave a comment