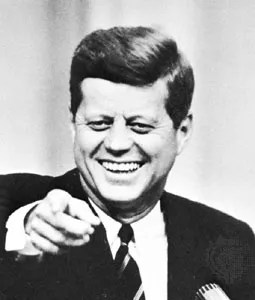

John F. Kennedy would never have been elected President in 1960 if not for Estes Kefauver. Or so he liked to say.

When Kennedy was teeing up his Presidential run, he liked to extend a joking “thank you” to Kefauver. When Adlai Stevenson let the Democratic convention choose his running mate four years earlier, JFK made a spirited run for the position and nearly won it. But in the end, Kefauver beat him out for the VP nod.

Kennedy was upset about the loss at the time, but he later saw it as a stroke of good luck. The Stevenson-Kefauver ticket went down to a landslide defeat in November; if JFK had been on that ticket, he concluded, the loss would have killed his national ambitions before they could properly take flight.

It’s a tidy story, and it made for a nice campaign-trail punchline. And from the vantage point of history, Ike’s 1956 landslide looks inevitable. He was hugely popular, and he racked up 457 electoral votes and over 57% of the vote, both even higher than his 1952 totals. It would be easy to conclude that as soon as Eisenhower decided to run for re-election, his victory was a sure thing.

A closer look, however, tells a more complicated story. While it’s true that Ike was the favorite throughout the election season, polls suggested that the race tightened considerably in late September and early October, with a significant bloc of undecided voters. A pair of late-breaking foreign policy issues – the Suez crisis and the Hungarian uprising – created a rally-round-the-flag effect that benefited the incumbent.

What if the election had happened a few weeks earlier, though? What if Eisenhower had recorded a victory, but not a landslide?

Newsweek‘s October 15, 1956 issue offers a glimpse into that alternate universe. At the time, Eisenhower was considered a clear favorite, but not an overwhelming one. “No realistic pollster believes that Mr. Eisenhower can repeat his landslide performance of 1952,” the magazine stated.

Despite Eisenhower’s personal popularity, Newsweek reported that the incumbent was showing some weakness among “farmers and factory workers.” (This helps explain the Stevenson’s campaigns repeated plays for the farm vote, including that ridiculous ad in which Stevenson tried to pretend he was a farmer.)

Even Republican strategists conceded that the President looked likely to lose some states he had won four years earlier, including Tennessee, Virginia, Missouri, Oklahoma, Minnesota, and perhaps even Texas and Florida. (In reality, Eisenhower won every one of those states in 1956 except Missouri.)

If Stevenson had won back some of those states, however, Newsweek suggested that it wouldn’t be because of his own charms. “The Stevenson personality was just not winning over the independents in any great numbers, or even some Democrats,” they wrote. “To farmers and the blue-shirted men at the factory gates and the white-collared clerks in city offices, Stevenson was still too glib and high-hat.”

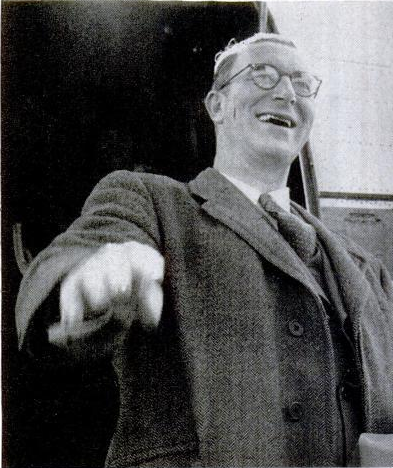

No, if the Democrats had rebounded in 1956 – and especially if they had pulled off an upset victory – much of the credit would have gone to what Newsweek dubbed “the homespun but effective efforts of Sen. Estes Kefauver.”

It was Kefauver, not Stevenson, who appeared on the cover of that issue. And Kefauver was the subject of the feature story, which highlighted just how popular he was with the constituencies that Democrats desperately needed to win back in order to have a chance at victory.

The feature article began by describing the flood of letters coming to Democratic Party headquarters from the Midwest and Great Plains states, asking for Kefauver to visit their towns. One example letter from rural Ohio stated, “It’s essential that we have Kefauver. This is farm country here, and we’ll do all right if we have Estes.”

“To the farmers in the great Corn and Wheat Belt,” the article said, “the No. 1 man on the Democratic ticket is not Adlai Stevenson but the folksy senior senator from Tennessee.”

The article went on to suggest that Democrats dreaming of a 1948-style upset considered that Kefauver might have the same plain-spoken appeal as Harry Truman had in that election. Kefauver was doing an excellent job using Agriculture Secretary Ezra Taft Benson, whom farmers hated, as a foil. (He’d been successfully banging on Benson since 1953, when he campaigned against the Secretary in order to help a Democratic win a solidly Republican Congressional seat in Wisconsin.)

The article noted that Kefauver was also a hit with labor, and that he’d been campaigning in factory and mining towns including Ironwood, Michigan, which hadn’t been visited by a Presidential candidate since William Jennings Bryan.

Like virtually every article about Kefauver in the national media, the Newsweek piece pondered the perpetual mystery of what made voters like the Senator so much, despite his notorious reputation as a dull and fumbling speaker. Like many such articles, Newsweek concluded that Kefauver came off as a “comfortable old friend” to many voters. They suggested that farmers, in particular, considered him one of their own:

Like many farmers, he is big and tall (6 foot 3 inches, 220 pounds); he moves with grave dignity, restrains anger, sweats profusely, and rarely looks well-groomed. With his sun-reddened face and big hands, he could easily pass for a helpful county agent, or the man at the feed store who lets the bill run.

They also noted that while Kefauver’s speeches were often poorly delivered, they were carefully tailored to speak about issues that mattered to the local audience.

Along with this feature, Newsweek ran a companion piece by Chicago bureau chief Robert Fleming, who traveled to Iowa County, Wisconsin to gauge whether Kefauver was really as popular with farmers as the Democrats claimed. (Think of this as an early version of the infamous “diner safari” articles from 2016.)

Fleming found that the effect was real; many of those he spoke to had backed Ike in 1952 but planned to vote Democratic in ’56, and many of them cited Kefauver as the reason. “Kefauver proves that [Democrats] consider the workingman,” said one voter. “He’s like us.”

As it turned out, Ike won Iowa County with over 60% of the vote. This actually represented a significant drop-off from 1952, when he’d captured 69.4% of the vote in the county. In Wisconsin as a whole, the President won with 61.5% of the vote, a slight increase over the previous cycle.

Based on the state of the race as it appeared at the time, Newsweek proclaimed that Kefauver would come out looking great. “If the Stevenson-Kefauver ticket loses, Stevenson is through as a presidential possibility – but not Kefauver,” they wrote. “He’ll be stronger than ever in ’60.”

As we know, that turned out not to be the case. Ike romped to such a huge victory that both Stevenson and Kefauver were essentially finished as national candidates. The farm vote did move away from the GOP a bit, but the overall effect was too small to make much difference. Kefauver didn’t even bother trying for the Presidential nomination in 1960, choosing to run for re-election to his Senate seat instead.

Obviously, none of this is proof that Kefauver would have been the Democratic nominee in 1960 if the ’56 election had been closer. Kennedy (and Lyndon Johnson) would have been a formidable opponent regardless. And Kefauver’s refusal to maintain an organization outside of elections meant that he might not have benefitted as much as he should have from his own popularity.

Still, it’s interesting to think how much might have been different if the 1956 election had occurred in October, before Suez and Hungary, rather than November. If Ike had wound up with 52% of the vote instead of 57%, and if he’d won closer to 350 electoral votes rather than 450, it would have changed the entire narrative around the election. And Democrats might have been left kicking themselves that they’d put Stevenson on top of the ticket instead of Kefauver.

Leave a comment