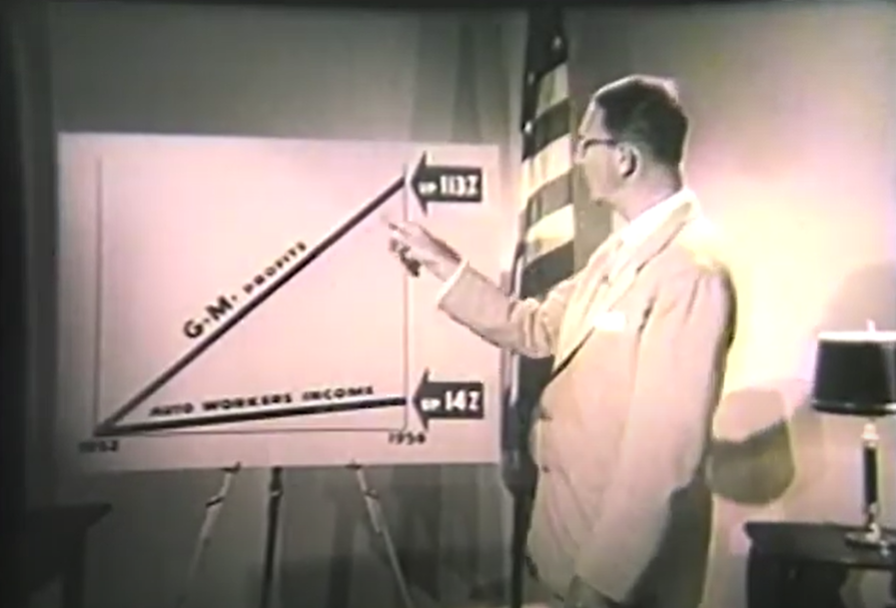

Estes Kefauver was a big believer in the power of congressional investigations. His subcommittee’s televised investigation of organized crime turned Kefauver into a national hero and plausible Presidential candidate. In the last years of his career, he held a series of investigations into anti-competitive practices in industries ranging from cars to bread to prescription drugs.

But while Kefauver strongly supported the right of Congress to perform investigations on behalf of the people, he knew that this power could be abused.

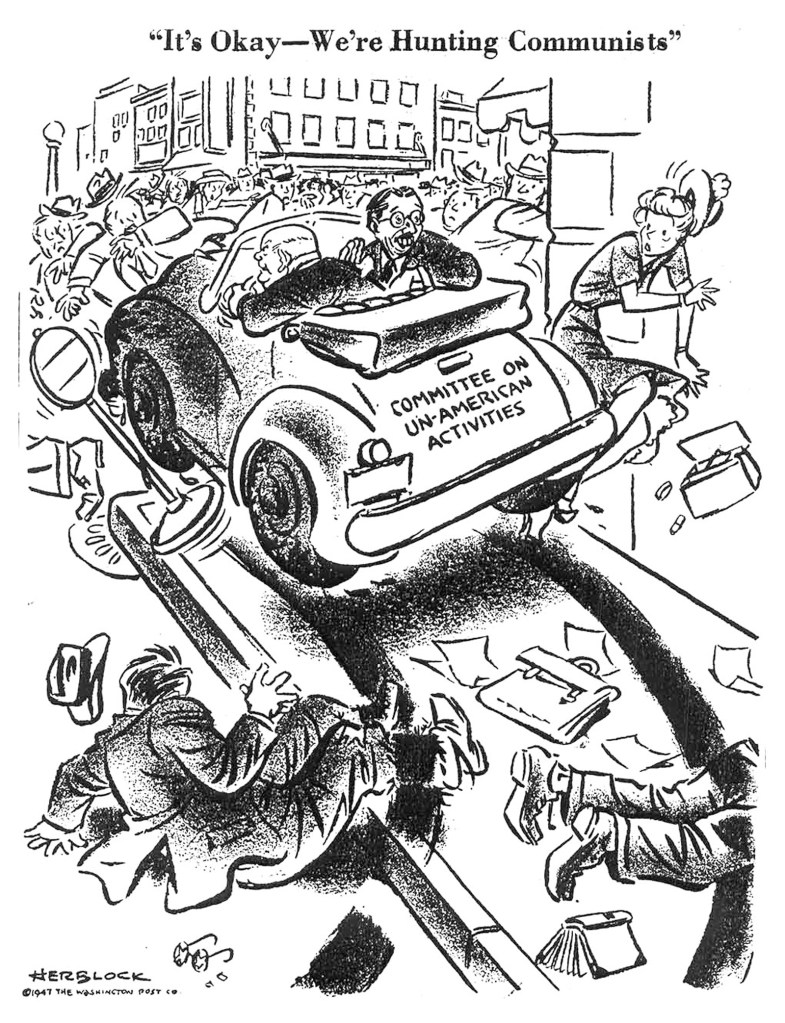

Like many others, he was worried about the House Un-American Activities Committee, where allegations of subversive activities and Communist associations were used to destroy people’s lives and careers. And as a Senator in the early ‘50s, Kefauver had a front-row seat for Joseph McCarthy’s reign of terror, as the Wisconsin Senator and his allies carelessly tossed around charges that the government was honeycombed with traitors and subversives.

These abuses troubled Kefauver for a couple of reasons. First, as a strong supporter of civil liberties, he was horrified that a weaponized investigation – or even just some loose remarks on the floor of Congress – could ruin the life of an innocent person who frequently had no ability to fight back.

Second, as he explained to the Arkansas Bar Association in 1953, he worried that if Congress abused its powers of investigation, “an aroused public may demand a termination or a great cutting down of congressional investigation to the point where the legislative process might be harmed.”

In order to avoid these outcomes, Kefauver lobbied both houses of Congress to adopt a code of conduct for committees and investigations. If Congress had acted promptly, they might have managed to prevent some of the worst abuses of the Red Scare. Unfortunately, this was yet another area where Kefauver’s warning calls went unheard.

When Investigations Went Overboard

Kefauver was hardly the first person to express concerns in this area. As early as 1885, Woodrow Wilson was grumbling about “the special, irksome, ungracious investigations which [Congress] from time to time institutes.”

But things changed in the 1940s with the rise of HUAC, which was charged with ferreting out disloyal or subversive conduct among Americans. Suddenly, instead of the primary concern being that investigations were annoying to the executive branch, the fear was that Congress was violating citizens’ Constitutional rights.

Senate Majority Leader Scott Lucas began pushing for reform in the late 1940s, describing his shock that there was no committee code of conduct. But his proposals couldn’t get out of committee.

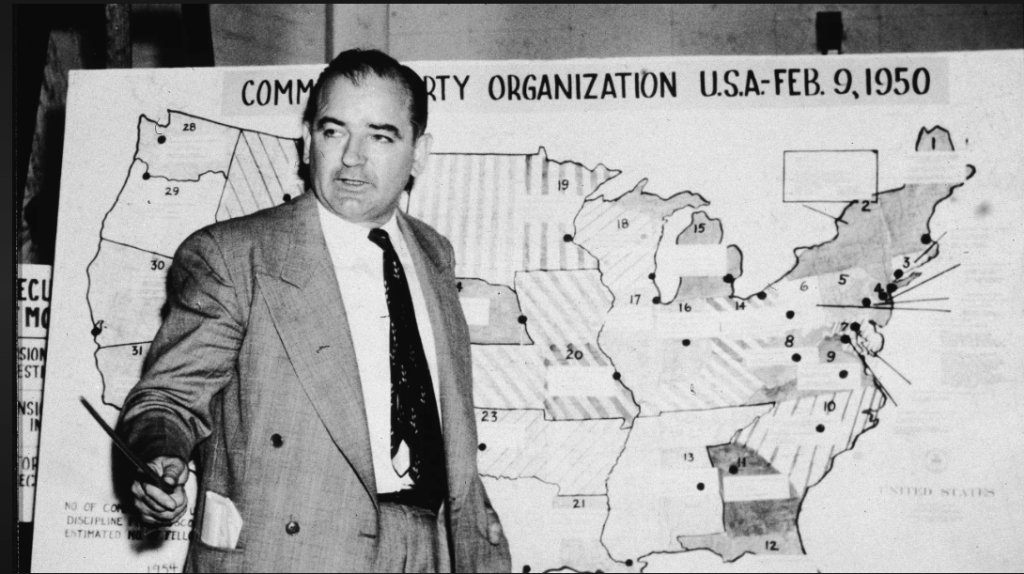

The situation only got more heated thanks to McCarthy, who gained national attention in 1950 with his claim that the State Department had a number (which kept changing) of Communists in its ranks.

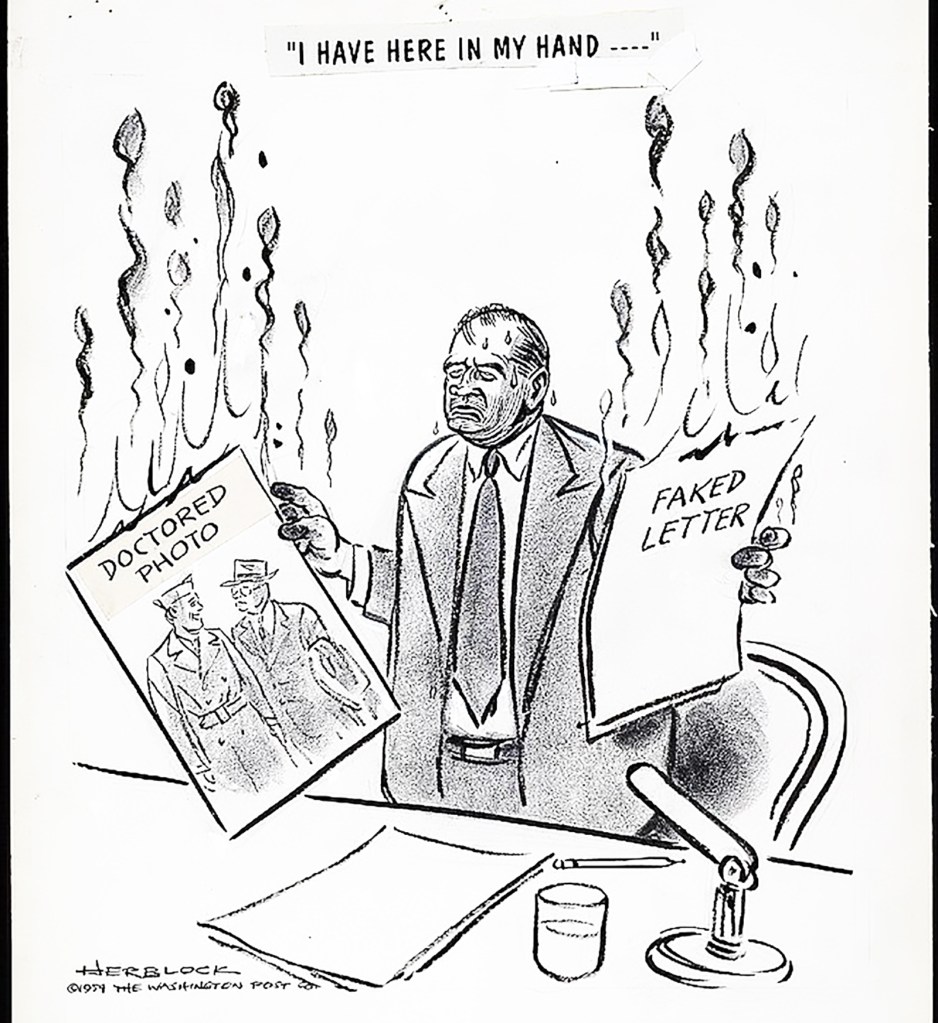

McCarthy’s habit of making wild accusations of treason and disloyalty on the floor of the Senate drew widespread condemnation. However, there was little that the critics could do about it, since Article I, Section 6 of the Constitution protects members of Congress from being prosecuted for anything they say on the floor.

So McCarthy could freely fling scurrilous charges at opponents and government employees without facing any legal danger, while his targets could have their careers ended and lives ruined with no way even to respond.

At the same time McCarthy was becoming a national figure, so was Kefauver, thanks to his organized crime investigation. Kefauver’s hearings were far less controversial than HUAC or McCarthy’s anti-Commie crusade, but they did also have their critics, who worried that being subjected to televised questioning implied that witnesses were guilty, whether or not it was true.

To his credit, Kefauver took these concerns seriously, and wanted to do something about them. So in August 1951, he introduced a pair of bills to change the rules of the House and Senate to curb the abuses and safeguard the rights of the accused.

Kefauver Proposes A “Nonpartisan” Solution

Kefauver’s first bill and the speech he made supporting it were drawn heavily from Dr. George Galloway’s article “Congressional Investigations: Proposed Reforms.” Galloway had led the effort to reform congressional procedures in the mid-1940s, an effort that Kefauver had strongly supported.

This bill required committees to notify people and organizations before subjecting them to investigation or presenting negative information about them. It gave the accused a chance to present evidence or witnesses on their own behalf, to have a lawyer present at the relevant hearings, and to present a rebuttal at the end of the hearing.

The bill prohibited committees from questioning people about their private affairs or their political or religious beliefs, or from questioning witnesses in closed hearings, unless a majority of the committee voted that it was necessary.

It prevented committee members from making derogatory comments about witnesses until the final report was files, and required verbatim records of all hearings to be available to the public.

Kefauver said this bill “would give Congress and the country a yardstick by which to test the performance of every committee instigation.” He lamented that “charges made before committee hearings, sometimes… devoid of foundation, have the tendency to convict, in the minds of the public, those persons against whom such charges are made.”

Kefauver’s second bill addressed the problem of members of Congress attacking private citizens on the floor. The bill required members of Congress who intended to make derogatory remarks about someone to notify the target of those remarks in advance. If the member did not provide advance notification, the target would be sent a printed copy of the remarks afterward.

In either case, the target of the remarks would have the chance to submit a response, which would be read on the floor of the chamber where the original remarks occurred and printed in the Congressional Record.

Kefauver said that this bill “seeks to preserve that freedom of debate but it seeks also to give an individual whose reputation may be harmed… the opportunity to defend himself. It seems to me that this is a fundamental concept – the concept of self-defense.”

Noting that his bills were just a starting point, he urged both parties to work together to devise a solution. “I plead with Senators to think of these resolutions in this nonpartisan light,” he said. “If we are ever to solve the problem, we must approach it without partisan bias – without seeking any partisan gain.”

Unfortunately, this wasn’t a high time for bipartisan cooperation. Kefauver’s bills couldn’t even get a hearing in committee, much less a vote. Both houses of Congress – and the Senate in particular – were headed for a period in which the parties would battle closely for control. And the problem of unfounded accusations was only going to get worse.

The Inmates Take Charge of the Asylum

In 1953, riding on the wave of Dwight Eisenhower’s landslide victory, Republicans took control of both houses of Congress. The Senate Internal Security Subcommittee – the Senate’s answer to HUAC – was now run by far-right Sen. William Jenner, who brushed off calls for formal rules of procedure, claiming “everyone gets fair play.” And the newly renamed Permanent Subcommittee on Investigation was now in the hands of – you guessed it! – Joseph McCarthy. What could go wrong?

That May, Kefauver reintroduced the same bills he’d submitted two years earlier. Rather than exhaust himself making another speech, this time he submitted printed remarks that echoed many of the points he’d made in 1951.

This time, however, he added a criticism aimed directly at Jenner and McCarthy: “Another objection – somewhat intangible – but of great danger to a democracy,” he wrote, “is the fact that conformity to prevailing ideas is enforced by fear of censure before a congressional committee.”

Kefauver’s bills were again sent to committee, where they sat unheard. The House Rules Committee held hearings on their version of the committee conduct bill, but – you’ll never believe this – the Republicans on HUAC objected, complaining that “hard and fast” rules on procedure might be twisted by witnesses and their lawyers to avoid questioning. After two and a half weeks of hearings, the Rules Committee gave up and postponed further discussion until the next year.

In May 1954, Kefauver was back with a new “Code of Conduct for Congressional Committees,” which attracted 17 cosponsors. However, the list of co-sponsored demonstrated that his previous call for bipartisan debate had proved hopes. While both of his 1951 bills had multiple Republican cosponsors, this new bill’s cosponsors were all Democrats – with the exception of independent Wayne Morse, who would become a Democrat the following year.

The Republicans were determined to come up with their own code of conduct – which, it soon became clear, was no code at all.

In late February of 1954, the Republican Senate Policy Committee asked its chairman, Homer Ferguson of Michigan, to study the investigative practices of the committees and coming up with some recommendations. Ferguson quickly announced that any change would need to come from the committee chairmen themselves. He duly came up with a list of recommendations, while making clear that there would be no consequences for chairmen who violated them. Amazingly, this had no effect.

As the year wound on, however, McCarthy’s antics became bad enough that GOP leaders felt the need to do something. The Senate Rules Committee finally held hearings on the passel of proposals in the summer of ’54. The Democrats testified in favor of the Democratic proposals and the Republicans testified in favor of the Republican proposals. McCarthy loudly denied doing anything wrong and said his subcommittee had “an almost ideal set of rules.” The HUAC guys showed up to complain that overly restrictive rules might let dirty Commies get away unpunished.

In the end, the Rules Committee took no action on any of the proposals. It’s probably worth noting that the chairman of the Rules Committee was… William Jenner.

Postscript: Don’t Just Do Something, Stand There!

After McCarthy was censured in the fall of ’54, the Senate generally seemed happy to agree that he had been the problem and to drop the whole code-of-conduct issue.

It took another decade for the Senate to establish a Committee on Standards of Official Conduct (later renamed the Committee on Ethics), and that was focused more on the wrongdoing of individual members rather than committees.

In the late 1950s, the Supreme Court waded into the fray, limiting the power of HUAC to compel individuals to testify about their political affiliations in cases like Watkins v. United States and Barenblatt v. United States. Those decisions generated a fight all their own… which is a story for another day.

Leave a comment