When Estes Kefauver became chairman of the Senate Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee, reaching a goal he’d long sought, he wasted no time launching investigations into what he viewed as anti-competitive practices in American business.

In particular, he focused on industries which were characterized by what he described as “administered prices”: industries where a handful of large firms had a dominant share of the market, and rather than compete on the basis of price or efficiency, they colluded (to varying degrees) to set prices at levels that ensured everyone’s profitability. It was a great deal for the companies, but not so great for the consumer.

Kefauver’s investigations included (then) major American industries such as steel production, auto manufacturing, and prescription drugs. One of the industries his subcommittee studied, however, seemed a bit different than the others: bread baking.

On one level, especially at the time, bread did not seem like an industry that was particularly prone to national consolidation. The product is extremely perishable and relatively expensive to ship; at the time, almost all bread on store shelves was manufactured no more than 50 or 60 miles from where it was sold. Unlike some industries, there weren’t any real economies of scale; in fact, the largest baking firms testified that their small local competitors were generally more efficient than the giants.

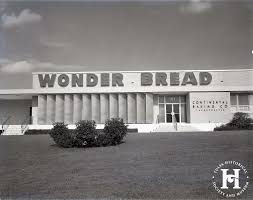

Despite all this, the bread industry was consolidating rapidly in the 1950s. Between 1947 and 1958, the number of wholesale baking companies in America fell from 6,000 to fewer than 5,300. In 1958, the top four wholesale bakers controlled 22% of the market and the top eight bakers held 39% of the market.

In pretty much every American city by the late ‘50s, the major bakers controlled the market, having either acquired or driven out their smaller local competitors. Not content to stop there, the big bakers were in the process of expanding their dominance into smaller cities, squeezing out local operations that had operated for decades.

How did the big bakers pull this off? Through a combination of aggressive business tactics and pressure gambits seemingly adopted from another field that Kefauver had investigated before: organized crime.

In his book In A Few Hands, Kefauver illustrated the problem via the testimony of a small independent baker in Meadville, Pennsylvania (a small town about 40 miles south of Erie). The bakery’s owner purchased the company from his father-in-law in 1944; over the next six years, he increased sales from $150,000 to nearly $1 million annually.

Over time, the baker’s success attracted the attention of two of the big boys, Ward and Continental, both of whom had plants in Youngstown, 60 miles away. Each company offered to buy the Meadville baker, offering a competitive price. After he’d turned over crucial information about his routes and customers, however, they pulled the rug out from under him. Ward tried to cut their offer by a third when the baker showed up to finalize the sale; Continental dropped their offer entirely.

When the Meadville baker refused Ward’s lowball offer, he said, a company rep warned him, Mafia-style, “that if they wanted that bakery badly enough, there were other ways to get it.”

“Nice bakery you got there. Be a shame if something happened it.”

He soon discovered this was no idle threat. Both Ward and Continental immediately cut the prices of their bread in Meadville, selling it for less than they charged in Youngstown, where the plants were located. They held their prices at the same level for the next eight years.

The independent baker also ran into trouble with the unions who represented his drivers and factory workers: the Teamsters (speaking of organized crime!) and the Bakery and Confectionery Workers, respectively. Both unions had been booted out of the AFL-CIO for corruption and criminal ties, and were revealed by another Senate investigation to be colluding with the big bakers.

The Teamsters demanded to renegotiate their deal, demanding much higher wages, saying that Ward and Continental wouldn’t negotiate until the Meadville baker agreed to terms. When he replied that he couldn’t meet their demands and stay competitive, they said, “If you can’t compete, get out of business.”

Shortly thereafter, the business agent for the Teamsters local in Meadville was suddenly named agent for the Bakery and Confectionery Workers local, who immediately tried the same tactic. In both cases, the workers sided with the baker against the union. The drivers quit the Teamsters; the factory workers stayed with their local, only for the national BCW union to take away their bargaining power and assign it to the local in… Youngstown.

At the same time, a lot of the local grocery stores in Meadville (the baker’s primary customers) were closing, forced out by chain supermarkets. The baker tried to negotiate deals with the chains, only to find that every time, Ward or Continental would swoop in at the last minute and undercut his offer.

After almost a decade of these hardball tactics, the Meadville baker finally gave up and folded in the summer of 1958. “I simply closed the door,” he said. “I had nothing to offer.”

Kefauver said that the Meadville baker’s testimony was typical of the stories the subcommittee heard from small bakers around the country. The big guys were using their size to engage in “discriminatory practices” that the little players couldn’t afford to copy.

One common tactic was to offer artificially low prices in markets where they were trying to kill off competitors. (As described above, they’d sometimes sell bread cheaper in outlying areas than in the city where their plant was located.) The big bakers could offset the losses with profits elsewhere, but smaller bakers – who generally owned only one or two plants and served a single market – had no such margin. They could either hold the line and bleed sales, or match the big boys’ prices and go broke.

Strangely, this kind of price competition never seemed to occur in cities dominated by multiple big firms – only in smaller towns with small local competitors.

But cutting prices wasn’t the only way that big bakeries put the squeeze on their smaller competitors. There was also the practice of “slugging” or “stales clobbering,” where big bakeries would provide huge piles of their products, making their products more visible and crowding competitors out of limited shelf space. Since bakeries traditionally agreed to take back any unsold products, this was a tactic that would be very costly for small firms to copy.

Another pricing tactic was to offer special discounts to higher-volume customers, while charging more to smaller ones. This cut against small businesses both ways: it obviously hurt small bakers who couldn’t afford to offer discounts, and since the discounts usually went to chain supermarkets, it also hit struggling small grocers.

In other cases, big bakeries entering a new markets might offer their bread for free, or provide new display racks or store paint jobs for grocers who signed up with them. In other cases, they would offer thinly-veiled bribes, in the form of off-the-books payments for “preferred rack position” or for “promotions” that never actually happened. Again, small bakers didn’t have the margins to play these sorts of games.

And did these tactics wind up benefitting consumers? Not at all. One study found that between 1947 and 1960, the price of bakery products increased more than any other group of food products. And the subcommittee found that as in the steel and auto industries, when one of the big bakers raised their prices, their competitors quickly followed suit. So customers were paying more for less competition. A great deal for the big bakers, but not for the shoppers.

As Kefauver pointed out in In a Few Hands, this wasn’t just a story about bakers. “None of these discriminatory practices is either new or unique to the bread industry,” he wrote. “Their danger stems from the fact that they widen the gap between big and small units and virtually guarantee the extinction of the smaller firm.”

Traditional economic theory holds that if an established company tries to hoard too much profit for itself, it will be outcompeted by smaller, more efficient competitors. But as the subcommittee’s investigation of the bread industry demonstrated, bigger firms can use their sheer size to push smaller firms out of the market, even if those firms are more efficient or make a better product.

And lest we think these practices went away decades ago, they are very much still practiced today. See this video, in which the dominant players in the potato growing industry – along with several others – are hiking prices in a way that would seem very familiar to Kefauver:

The video calls it “algorithmic price fixing,” but it’s essentially the same administered-price behavior Kefauver’s subcommittee studied in the 1950s with a slightly different slant.

As for strategically underpricing as a tactic to wipe out competition – look at how Amazon got its start, or Uber, or any number of other tech firms. Instead of using profits from other locations to offset temporary losses, as the big bakers did in the ‘50s, they’re using venture capital to bankroll their attempts to price the competition out of business. Then once they’ve established a dominant position in the industry, they start jacking prices up.

It’s ironic that after Kefauver died in 1963, many observers considered his obsession with antitrust and the anti-competitive practices of big business to be an outmoded relic of a bygone era. Less than a year after the Senator’s passing, historian Richard Hofstadter was asking “What Happened to the Antitrust Movement?” and claiming that Kefauver’s interest in the subject was “one of the faded passions of American reform.”

In truth, these practices have never gone away, and the problems Kefauver worried about are perhaps even more prominent today than they were in his time. If ever there was a moment that cried out for a successor to Kefauver’s subcommittee and its tireless investigations, it is now.

Leave a comment