As I’ve mentioned previously, Estes Kefauver pushed for political reform throughout his career in Congress. As his former law partner Jac Chambliss said, “Estes had the zeal of the born reformer. He had no sooner gotten into Congress than he wanted to change things.”

Being a Congressional newcomer, few of Kefauver’s initial proposals were adopted. But in a demonstration of his legendary persistence, he continued promoting his ideas year after year, slowly trying to persuade his colleagues to go along.

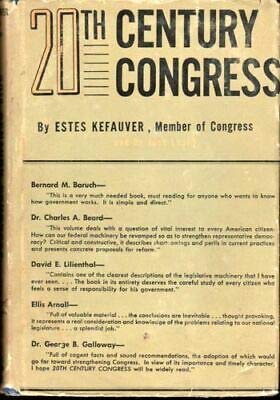

By 1947, Kefauver had served four terms in the House, and he had observed many ways in which he believed Congress could function more effectively. He turned his proposals into a book, entitled A Twentieth-Century Congress, co-authored with Dr. Jack Levin. Although few of his proposals were adopted, the book attracted nationwide attention and marked Kefauver as an up-and-coming politician to watch.

Congress: A 19th-Century Institution in a 20th-Century World

Kefauver was hardly alone in calling for Congressional reform in this period. The New Deal and World War II had led to a dramatic expansion in the size and complexity of the federal government. And Congress was struggling to keep up.

The number of committees in both the House and Senate had spiraled out of control. Many committees had overlapping jurisdictions and were constantly arguing over which one was responsible for what. Members’ schedules were jammed full of committee meetings, and the legislative calendar was clogged with mundane matters like resolving pension appeals and private claims against the government.

As for those committees, they generally only had a few poorly-paid clerks for staff support – generally friends or political cronies of the chairman. Similarly, members’ individual staffs largely consisted of administrative support. Committees and members had little professional help in considering bills and issues, some of bewildering complexity. As a result, they relied heavily on lobbyists to review and even craft legislation.

Meanwhile, FDR had staffed the executive branch with his “brain trust” of bright young policy wonks. Congress was supposed to oversee the activities of the executive branch, but they were largely relying on the knowledge and capacity of their overworked members. How could they effectively keep an eye on the executive branch when they were struggling to keep up with a flood of bills and administrivia?

Also, both the House and Senate relied on the seniority system for selecting committee chairmen. In some cases, this meant that committees were being run by men too ill or feeble to do the job effectively. And it generally meant that committee chairs were more conservative than Congress as a whole, and much more conservative than the Roosevelt administration. In the House in particular, things ran the way the old bulls wanted them to – which greatly frustrated younger members, particularly reform-minded ones like Kefauver.

Congress Attempts to Clean Up Its Act

Attempting to spark change, in 1941 the American Political Science Association (of which Kefauver was a member) created a Committee on Congress to study the issues and recommend solutions. The committee, chaired by Dr. George Galloway, published its findings in 1945.

It sketched a picture a lot like the one in the section above, concluding that Congress lacked the capacity to effectively inspect and review the executive agencies it was supposed to oversee, as well as the ability to effectively develop its own policy priorities. Further, the committee concluded that power was too heavily vested in leadership, especially in the House.

In response, Congress created a joint House-Senate committee to recommend legislation. The committee was headed by Sen. Robert LaFollette Jr. of Wisconsin and Rep. Mike Monroney of Oklahoma, both champions of reform. The committee also had the support of Dr. Galloway, who served as staff director.

The committee’s ultimate output was the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 (known informally as the LaFollette-Monroney Act). This was the first major reform of Congressional operations since the country’s founding, and unsurprisingly (given Galloway’s involvement) it borrowed heavily from the APSA’s recommendations.

The Act dramatically reduced the number of standing committees in both houses, going from 48 committees to 19 in the House and 33 to 15 in the Senate. It increased Congressional staff support: allowing each committee to hire four professional staff members (with the salaries to match), expanding the Legislative Research Service, and strengthening the bill drafting service. It prohibited the White House from detailing staff to Congressional committees to help with drafting bills (a trick FDR used to ensure friendly legislation). It required lobbyists to register and submit reports detailing their activities.

Supporters hoped the reforms would alleviate the burden on individual members. As Monroney said, their work had “expanded by geometric proportions in recent years and we must modernize our machinery to handle it.” Reformers also hoped the Act would help Congress reclaim some of the power and prestige it had lost to the executive branch in recent decades.

Unfortunately, senior leadership in both houses was generally skeptical of reform, and they did their best to keep the Act from succeeding.

They handicapped the LaFollette-Monroney committee from the start by preventing them from making recommendations about legislative procedure. During the negotiations over approval of the Act, anti-reform forces knocked out some of the proposals, such as giving DC home rule (nixed to appease racist Southerners) and running the hiring of staff through a Congressional personnel director (vetoed by old-school pols like Sen. Kenneth McKellar, who relied on patronage jobs as a key source of power).

Then once the Act was passed, some of its provisions were undermined by the hostility or indifference of leadership.

For instance, a new forest of select committees and subcommittees sprang up to replace the committees that the Act had killed. The Act also required that committees hold hearings that were open to the public; this rule was ignored by the powerful House Appropriations Committee. An innovative proposal for Congress to kick off the annual appropriations process by developing its own budget for consideration by the White House was tried halfheartedly for a couple years and then dropped.

In short, the LaFollette-Monroney Act was a good start, but almost everyone agreed that more work was needed. Kefauver evaluated the Act’s progress in a National Municipal Review article entitled “Did We Modernize Congress?”, ultimately calling for further reforms.

Kefauver wrote, “We want to give Congress real independence and actual political freedom to enable it to respond quickly and effectively to the will of the millions it represents – the American people.” He argued that continuing the work begun by the Act might be essential to “the preservation of democracy in the United States.”

A Twentieth Century Congress was a call to arms to continue the work that the LaFollette-Monroney committee had started.

Kefauver to Congress: Shape Up, Democracy Is At Stake

Kefauver’s book makes a powerful case for change in the way Congress did its business. In the preface, he expresses his personal frustrations as a legislator, bemoaning the fact that “outmoded legislative machinery made it difficult to get much done” and expressing concern that Congress “was ill equipped to chart the legislative program of the nation.”

In the first chapter, boldly titled “Is Congress Necessary?”, Kefauver argued that Congress’ inability to react effectively to the Great Depression opened the door for FDR to dramatically strengthen the executive branch, to provide the bold action needed to help a destitute and desperate populace.

With World War II fresh in the rear-view mirror, Kefauver suggested America was fortunate that FDR had been a benevolent leader. He argued that Germany, Italy, and Spain all turned to fascism when their legislatures failed to deal with the countries’ problems. “The people were in a mood to accept as a palatable substitute even for democracy any formula that would save their jobs, their homes and farms, and their lives,” he wrote.

Kefauver argued that reform wouldn’t just stave off a potential authoritarian future, but also restore Congress’ sullied reputation. “For two decades the national legislature has been subjected to an endless stream of ridicule, scorn, and even contempt,” he wrote. “A generation has reached maturity with a dangerously cynical attitude toward the legislative process.”

A Vision of a Modern Congress

What solutions did Kefauver propose? In some cases, he endorsed ideas originally proposed by the LaFollette-Monroney committee, such as home rule for DC (see my previous post on that) and putting real teeth into the limits on lobbyists. But other ideas were in areas that the committee had not gone, or not been allowed to go.

For instance, the committee had been forbidden to change the Senate filibuster. Kefauver proposed allowing cloture by a majority vote. (At the time, cloture required a two-thirds vote; in 1975, the Senate reduced the threshold to 60 votes, where it remains today.) This idea helped make Kefauver persona non grata among his fellow Southerners, who routinely used the filibuster to prevent action on civil rights bills.

Kefauver also proposed abolishing the practice of choosing committee leaders by seniority alone. Instead, he recommended that the chairmen and ranking member (that is, the leader of the minority party) be chosen by secret ballot. This would ensure that committee leaders were capable of doing the job and that their views weren’t wildly out of step with the rest of the committee.

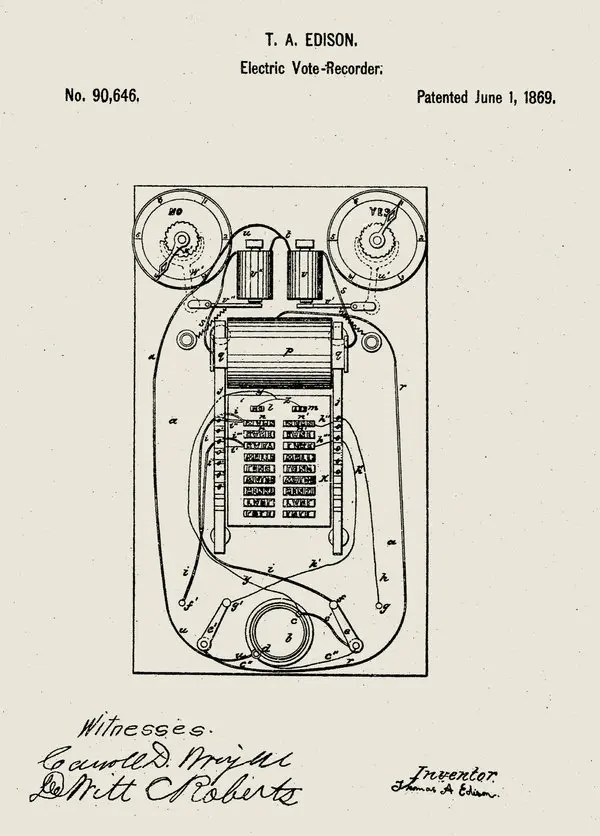

He also proposed scrapping the system of voting by roll call, instead recommending that members record their votes electronically. This wasn’t a radical new concept; Kefauver pointed out that Thomas Edison had first patented an electric vote recording system in 1869, and that the Wisconsin state legislature had been doing it since 1917. (Amazingly, it wasn’t until 1973 that the House finally enacted electronic voting.)

Most of Kefauver’s suggestions were simple rule changes; however, a couple would require Constitutional amendments. One such proposal was to lengthen the terms of House members from 2 to 4 years. As Kefauver noted, “The present period of two years barely gives [a new Representative] time to begin his public duties before he has to prepare the next primary.” This problem has only gotten worse since then due to the increasing need for fundraising.

His other proposed amendment would do away with the requirement that treaties be ratified by a two-thirds vote of the Senate, instead suggesting that they be ratified by a majority of both houses. Kefauver pointed out that the Senate’s supposed role of “advice and consent” on treaties had never really been enacted, and that the two-thirds threshold made it all too easy for a band of isolationists to kill any treaty they didn’t like, even one that was widely popular.

He also pointed out that FDR had made increasing use of executive agreements in order to make international accords without having to get the consent of a recalcitrant Senate. (In a way, this section was a warmup for the debate over the Bricker Amendment – which proposed drastic limits on the President’s ability to make treaties – a few years later.)

Perhaps Kefauver’s most treasured proposal was a report and question session, to occur once or twice a month, in which the head of an executive branch agency would appear before a joint session of Congress, provide a report on the agency’s work, and answer member questions (some submitted in advance, others asked live).

Kefauver had first proposed this idea a few years earlier. He was inspired by the informal meetings the Army held during World War II to keep Congress up to speed with events. These were essentially lectures, and the members of Congress weren’t permitted to ask questions.

Kefauver felt that regular sessions – with questions this time – would allow members to keep up to date on the business of the executive branch without having to pore through committee reports, and would allow the executive and legislative branches to share ideas and work out disputes in a public forum.

Congress Hits Snooze Button on Kefauver’s Wake-Up Call… And They’re Still Sleeping

Sadly, Kefauver’s report-and-question proposal was never adopted. And while the ideas in A Twentieth-Century Congress were generally applauded political scientists and reporters, they were essentially dead on arrival in Congress. Having already pushed through one major reform bill, the legislature was in no mood to try again.

It would be two decades before Congress took another serious look in operational reform, and the bill that emerged from that effort wouldn’t be passed until 1970. In the meantime, power and influence continued to bleed away from Congress and into the executive branch. Congress made a belated effort to reassert its authority after the abuses of the Nixon administration in the 1970s, but this largely amounted to a holding action in a long, slow slide.

Today, Congress once again finds itself paralyzed and unable to act amid numerous pressing crises facing the country. And the actions of the current administration demonstrate that Kefauver was prescient when he said Americans might be willing to abandon democracy if they decided the legislature wasn’t capable of doing its job.

Kefauver’s specific proposals are (largely) no longer applicable to the present day. However, I agree with him that more than ever, we need a strong and capable Congress that is serious about governing.

I count myself among those who, as he wrote in his book, “want to see the federal legislature strong and able to cope intelligently with the increasing complexity of this advanced era.” And while that vision may feel like a pipe dream today, it may be our best hope of avoiding an autocratic future.

Leave a comment