In many ways, Estes Kefauver was a man ahead of his time. I’ve written a number of posts about his forward-thinking ideas, some of which would be just as relevant today as they were then.

At times, however, Kefauver said things that wouldn’t resonate so well with modern audiences. One of the most striking examples of this was his habit of praising the Confederacy.

No, Kefauver didn’t put the flag there, but he also didn’t obect to it.

Today, any positive mention of the Confederacy would be the third rail for a politician as liberal as Kefauver. How could the same man who refused to sign the pro-segregation Southern Manifesto, who spoke out against the poll tax, who voted for the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960, turn around and praise Southern secessionists? It doesn’t compute.

To understand this seeming inconsistency, let’s look at some examples where Kefauver cited the Confederacy and see if we can understand why.

Kefauver referenced the Confederacy briefly in his 1947 book A Twentieth Century Congress, which contained a variety of proposals for improving and modernizing the way the legislative branch does business.

One of his proposals was for the heads of executive departments and agencies to appear before Congress on a regular basis for a report and question period. To critics who considered this a radical proposal, Kefauver pointed out that such ideas had been proposed dating back to the beginning days of the Republic.

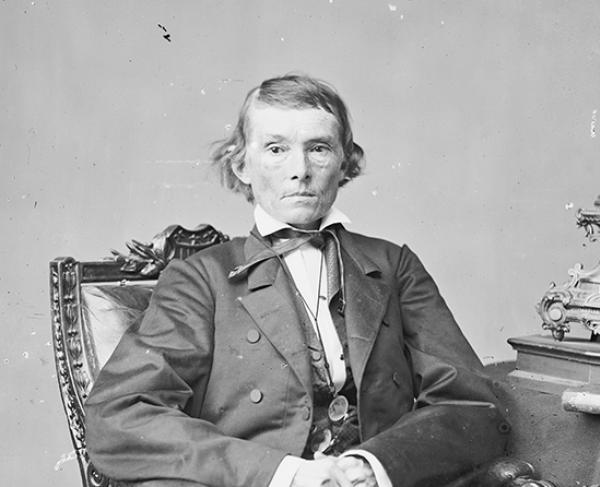

One of the examples he cited was a provision in the Confederate constitution authorizing cabinet members to appear before the legislature. Kefauver credits the proposal to Alexander Stephens, whom he referred to as “one of the great statesmen of his time.”

Stephens developed this idea because he felt “that the lack of consultation and coordination between the legislative branches and the Executive was one of the weaknesses of the Federal Government which the new government for the seceding states should avoid.”

Kefauver again referenced the Confederate constitution in 1953, while making a floor speech in opposition to the Bricker Amendment. For those who missed my post on the subject, the Bricker Amendment would have prohibited the President from making international treaties or executive agreements without having them approved by Congress. The amendment was popular with conservative Republicans, but also with Southern Democrats, who feared that the US might sign on to international treaties that outlawed or criminalized segregation.

As a pushback to those who favored the Bricker Amendment in the name of “states’ rights,” Kefauver pointed out that the Confederate constitution had the same language authorizing the president to make treaties that was in the US Constitution.

“I know of no more sincere advocates of States’ rights than the band gathered at Montgomery, Alabama, to form the Confederacy,” said Kefauver. “These leaders of our Southland knew that… no matter how great might be their allegiance to their individual States… that in external matters they, as individuals, would have to defer to the National Government. There is no other way for a nation to exist in the world.”

Kefauver again turned to the Confederacy to justify his opposition to a spate of conservative bills in 1957 that would have curbed the power of the Supreme Court, either by passing laws to overturn certain liberal decisions or taking away the Court’s power to hear certain types of cases altogether.

In a radio address broadcast across Tennessee, Kefauver pointed out that the last time such a maneuver was done, it was after the Civil War during Reconstruction. “The last time bar membership was denied was by reconstruction governments after the War Between the States,” Kefauver said, noting that the Supreme Court shot down the attempt.

“And the only time jurisdiction was ever removed from the Supreme Court was during reconstruction days. Congress passed an anti-Southern statute which President Johnson vetoed and then Congress overrode the veto. The Supreme Court ruled the statute unconstitutional and the anti-Southern Congress took jurisdiction away from the Supreme Court over reconstruction statutes.”

In the same year, Kefauver sponsored a bill making the former home of Robert E. Lee – which had been seized during the Civil War and turned into Arlington National Cemetery – into a national memorial to Lee. The wording of the resolution claimed that Lee had “never been suitably memorialized by the National Government” and called the general “a military genius [who] after Appomattox fervently devoted himself to peace, to the reuniting of the Nation, and to… the welfare and progress of mankind.”

For a proud liberal who was considered persona non grata by Southern segregationists in the Senate, Kefauver had an awful lot of complimentary things to say about the Confederacy. So what gives?

In some of the cases above, you can reasonably argue that Kefauver was using the logic of his opponents against them, something he was famous for doing.

In his argument against the Bricker Amendment, he effectively pushed back against the “states’ rights” (aka, pro-segregation) argument for the amendment: if even the Confederacy – the supposed bastion of states’ rights – refused to limit the treaty-making power of the president as this amendment proposed, how could one justify supporting it now?

Similarly, when he opposed the Court-curb bill, he argued that since the logic behind those bills had previously been used to deny rights to the South, it was a bad idea for Southerners to support the bills now. In both cases, he was speaking primarily as a Southerner to fellow (white) Southerners in their own language.

In addition, as a student of political science, Kefauver found the Confederacy an interesting test case. “The constitution of the Confederacy was written some 76 years after the Constitution of the United States,” he said in his anti-Bricker Amendment speech. “We had had a great deal of experience during that time.” Here, a group of Americans had a chance to creating a new government from scratch. What did they believe the Founders got right, and where did they see room for improvement? Kefauver saw value in looking at the historical example.

As for sponsoring the Lee memorial, it’s worth pointing out that the language in the resolution represented the broad consensus view of Lee among Americans at the time. (A less flattering picture of Lee has taken hold in the decades since, particularly among progressives.)

Also, America was approaching the centennial of the Civil War at the time, and the idea of a national monument to Lee was seen as a way of promoting sectional harmony. Lyndon Johnson also supported the resolution. (Ironically, Lee himself opposed the idea of creating public monuments commemorating the rebellion, as he felt they would be a barrier to the reconciliation of America.)

In short, I think Kefauver’s views toward the Confederacy were a mixture of smart politics and sincere belief. He represented a Southern state, and he knew that speaking the language of states’ rights and the Lost Cause would resonate with voters who might otherwise be inclined to disagree with him on the issues.

But he was also proud of his Southern heritage (see the Great Fish Battle of 1957), and I believe his admiration for men like Robert E. Lee and Alexander Stephens was sincere. Like most white Southerners of his era, nothing in his background would have given him any reason to feel ashamed of the Confederacy.

I can understand this. I grew up in Virginia and attended elementary school in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. And the way that we were taught about the Civil War, while not full-on Lost Cause, treated both sides as morally equivalent.

In fifth grade, we capped off our unit on the war by “reenacting” a battle as a water balloon fight. The teacher assigned some of us to the North and others to the South, like we were choosing up sides for kickball at recess. I was chosen to play J.E.B. Stuart, which I enjoyed because I got to take my “cavalry” and hide in the woods next to the “battlefield” and lead a charge in which we bombarded the Northern side with water balloons galore. I don’t recall who won, but my cavalry inflicted heavy casualties on our Union classmates.

Thankfully, this is not the way they teach the Civil War today, at least in my school district. (I’m pretty sure that any teacher who tried the water-balloon reenactment stunt today would be summarily fired.) But the point is that times change, and so does our understanding of our history.

A thornier question is whether that change is all for the good. I tend to think it is, mostly. But it’s probably not a coincidence that no one with Kefauver’s politics could get elected to the Senate from Tennessee today. And I’d certainly argue that his form of Confederate nostalgia is one of the less harmful ones. I’d rather put up with some dubious tributes to Confederate heroes than the looming sense that we might need to fight the war all over again.

Leave a comment