In recent years, the Supreme Court has come under fire. Thanks to the political gamesmanship of Mitch McConnell, the Court has a 6-3 conservative majority. Many of that majority’s decisions have angered liberals, who feel that the Court has ignored precedent to impose the results they favor. Given that there’s little hope of a liberal majority on the Court in the foreseeable future, some liberals are calling for major changes, like term limits for justices or an expansion of the size of the Court.

Conservatives decry these proposals as unconstitutional and blatantly partisan. They cite FDR’s court-packing fight from the 1930s as evidence that liberals are willing to rig the Court for their side. Conservatives, those self-described Constitutional originalists, believe that they would never stoop to such tactics.

This belief conveniently ignores the attempted conservative revolt against the liberal Court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren in the late 1950s, an episode that has largely been forgotten.

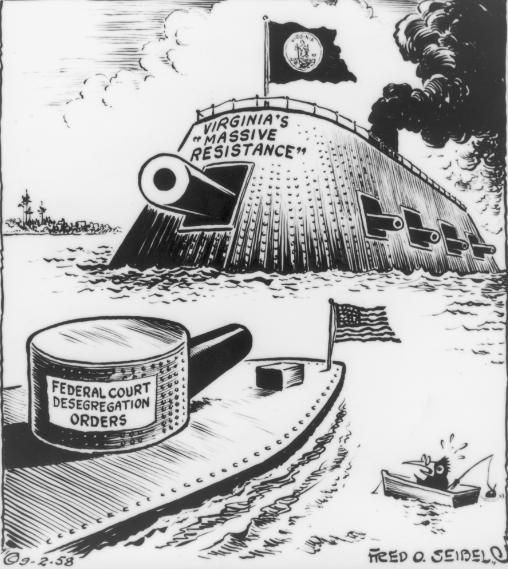

Yes, we remember the South’s fury against Brown v. Board of Education, and the Massive Resistance that arose in response. But school integration wasn’t the Warren Court’s only controversial ruling.

A string of liberal decisions on Communism and civil liberties sparked a broader conservative backlash, and Congress made a concerted effort to clip the Court’s wings, including proposals more radical than those of today’s liberals. (I touched on this in my piece on the Jencks Act.)

If not for some adroit legislative maneuvering by Lyndon Johnson, Congress might well have succeeded at dramatically limiting the Court’s power or changing the relationship between federal and state law.

It’s a shame that this conservative revolt against the Court has been largely forgotten, especially since it offered a preview of the right-wing coalition that would rise to power under Ronald Reagan. So over the next two weeks, we’ll take a look back at this forgotten chapter in American history.

Riling Up the Right

As mentioned above, Brown v. Board of Education was the decision that initially fueled outrage against the Warren Court. However, that alone wouldn’t have been enough to spark a nationwide pushback. Southerners were angry about integration, but they were a minority in both houses of Congress.

Conservative Republicans may have been sympathetic to Southerners’ arguments about states’ rights, but they considered school integration a sectional issue. And since the issue divided the Democratic coalition, Republicans were inclined to sit back and grab a bucket of popcorn rather than intervene in the dispute.

However, a string of Warren Court decisions in 1956 and 1957 soon had conservative Republicans as angry as their Southern colleagues.

- In Cole v. Young, the Court found that an FDA employee fired for associating with Communists had been wrongly dismissed, because his position was not related to national security.

- In Service v. Dulles, the Court found that the Secretary of State acted illegally in firing a foreign service officer for alleged disloyalty to the United States, ruling that he failed to follow State Department regulations.

- In US v. Yates, the Court held to a narrow reading of the federal anti-Communist Smith Act, ruling that alleged Communists could only be punished for specific actions or words that created a “clear and present” danger to the country, not just for advocating Communist ideas in the abstract.

- In Pennsylvania v. Nelson, the Court held that an alleged Communist could not be prosecuted under Pennsylvania’s state anti-subversion law, because the federal Smith Act preempted all state-level anti-subversion laws.

- In Watkins vs. US, the Court limited the investigative powers of the House Un-American Activities Committee, ruling that they could not punish witnesses for refusing to answer questions that weren’t “pertinent” to the investigation.

- In Konigsburg v. State Bar and Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, the Court found that states did not have the right to refuse admission to the practice law on the grounds of prior Communist affiliations alone.

In short, these rulings implied a broad concept of civil liberties, holding that neither national security nor the Communist threat were sufficient grounds for infringing Americans’ personal freedoms. They also effectively shut states out of making anti-Communist laws.

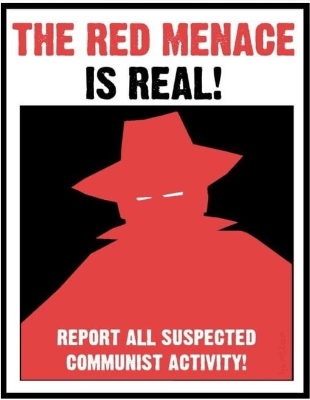

These decisions all came within the span of a year. Several of them – including US v. Yates and Watkins v. US – were released on the same day: June 17, 1957, which became known as “Red Monday.”

These rulings antagonized two overlapping but distinct groups of conservatives: those who felt that national security was more important than personal freedom, and anti-Red zealots who believed that the First Amendment and other civil liberties shouldn’t apply to alleged Communists.

When combined with those angry Southerners, they did constitute a cross-partisan Congressional majority, or close to it.

This anger resulted in a flurry of bills in both houses of Congress designed to bring the Court to heel, either by making laws effectively overturning the Court’s decisions, taking away the Court’s jurisdiction to hear certain types of cases, or changing the membership of the Court.

Some of the proposed bills would have taken away the Court’s ability to rule on school segregation laws, or on any state laws whatsoever. Others would have allowed Congress to overrule Court decisions by majority vote.

Others would have instituted term limits of between 4 and 10 years for Supreme Court justices or all federal judges; one bill would have subjected all incumbent Justices to a reapproval vote by the Senate. Still other proposals would have required Justices to have prior judicial experience (which was transparently aimed at Chief Justice Warren, but would have disqualified a surprising number of Justices).

Most of these proposals died before making it to the floor of either house. However, two bills made considerable headway. Each of them would have major implications for the Court’s powers.

The Smith Bill: States’ Rights on Steroids

The first bill was HR 3, introduced by Rep. Howard Smith of Virginia (author of the Smith Act and chair of the House Rules Committee). Smith’s bill decreed that no act of Congress would preempt or exclude state laws on the same subject unless Congress specifically added a provision to the act stating that it did, or unless there was a “direct and positive conflict” between federal and state law.

The bill specifically reversed the Court’s finding in Pennsylvania v. Nelson, but it also contained a general rule that federal laws would not preempt state laws on the same subject. Smith’s bill was retroactive, thus applying to the anti-Communist Smith Act… and to every other federal law.

The bill’s retroactive portion was its most far-reaching aspect. The Supreme Court had held for over a century that federal laws were considered supreme over state laws. Smith’s bill would reverse that presumption.

This prompted the Eisenhower administration to oppose Smith’s bill. Eisenhower was also annoyed by the Court’s decisions, particularly regarding the civil liberties of Communists (when Warren asked him how he would suggest resolving the issues, Ike reportedly replied, “I would kill the SOBs”).

However, the Justice Department recognized that overturning the supremacy of federal law would wreak havoc with regulation in areas such as interstate commerce.

When the bill came to the House floor, Rep. Kenneth Keating of New York relayed the administration’s objections, arguing that the retroactive feature would cause “serious difficulty” with enforcing federal law. That didn’t stop the House from approving the bill by a comfortable margin.

Upon its arrival in the Senate, Kefauver called out the bill’s sweeping nature and the unintended consequences that would result. “It would lead to endless confusion,” Kefauver said of the bill. “It would require someone to research all the laws passed by Congress for the past 150 years to determine whether they were or were not consistent. Then all of those previous acts would have to be repassed into law. I’d hate to try to operate a business and abide by the law, not knowing what the law is.”

But Smith’s bill wasn’t Kefauver’s only headache; the Senate was busy considering a Court-curb bill of its own.

The Jenner Bill: What’s So Supreme About the Supreme Court?

Senator William Jenner of Indiana was a hard-core Communist fighter, Joseph McCarthy’s longtime running buddy in the Senate. Even after McCarthy was censured by the Senate, Jenner remained faithful to the cause.

Jenner was horrified by the Warren Court’s apparent belief that Communists were entitled to the same civil liberties as other Americans. He proclaimed that the Court’s decisions would “confuse, disarm, and paralyze the people in their fight… against the world Communist conspiracy.” Given this treachery, Jenner said, it was “time to curtail the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.”

One month after Red Monday, Jenner filed a bill, S. 2646, to dramatically curtail the Court’s powers. His bill would deny the Court the ability to hear cases regarding the practices and jurisdiction of Congressional committees, enforcement of security regulations for federal employees, states’ control of subversive activities, school board regulations of subversive activities by teachers, and states’ ability to regulate admission to the bar.

Jenner founded his bill on the Exceptions Clause of the Constitution, which gave Congress the right to specify issues where the Supreme Court would not have appellate jurisdiction. This power had only been used once in American history, to prevent the Court from hearing challenges to the establishment of military governments in former Confederate states after the Civil War.

Nonetheless, Jenner said that the clause’s wording was “clear as crystal” in giving Congress the “full, unchallengeable power to pass laws immediately which would deprive the Supreme Court of appellate jurisdiction.”

The bill was referred to the Internal Security Subcommittee of the Senate Judiciary Committee, of which Jenner was a member. Jenner held a brief set of hearings at which he was the only subcommittee member present, and voted to report his own bill back to the full Judiciary Committee.

In early August, less than two weeks after he’d introduced his bill, Jenner testified in favor of it before his Judiciary Committee colleagues. “The right of appeal to the Supreme Court is not a constitutional right,” he insisted. “No man has a constitutional right to more than one trial. Due process does not require the judgment of more than one court. Any appeal procedure is a matter of grace, not of right.”

Jenner invited his colleagues to make the bill even broader. “[I]t may be there are other areas in which the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court should be restricted or… withdrawn,” he said. “[I]f in the judgment of the committee there should be additions to this bill, I hope the committee will make them.”

In spite of this appeal, several members of the Judiciary Committee – led by Kefauver and Sen. Thomas Hennings of Missouri – objected. They felt that the bill should go through a real set of hearings, and thus kicked the bill back to the subcommittee.

The Judiciary Committee liberals weren’t the only ones to object to Jenner’s bill. Attorney General William Rogers denounced it, claiming that Jenner was motivated by the “spirit of retaliation” and said the bill “threatens the independence of the judiciary” and “would be extremely detrimental to the administration of justice.”

In response, Jenner said that he’d introduced the bill “out of deep concern for the preservation of the Constitution” and said his goal was “to push the Supreme Court out of the field of legislation and back into the area where it was intended to operate.”

The American Bar Association also came out against the Jenner bill, passing a resolution in February 1958 opposing it. Numerous prominent lawyers and law school deans also testified against the bill during the subcommittee hearings, as did the NAACP and the ACLU.

But Jenner wasn’t going to let a bunch of Commie-loving lefties (and most of the legal profession) tell him he was wrong. Rather than let his bill die the inglorious death it deserved, Jenner would keep it alive – and a key assist from a sympathetic colleague soon gave it new hope.

Next week, we’ll learn about the key amendment that saved Jenner’s bill – and find out what happened when it and Smith’s House bill made it to the Senate floor.

Leave a comment