One of the fun traditions around this time of year is the Congressional football wager. Before a major bowl game, or the Super Bowl, the Senator or Representative from the hometown of one of the teams will make a friendly bet with a Senator or Representative from the other team’s hometown.

Usually both sides will bet some famous local food on the outcome. For example, before the 2023 Super Bowl between the Philadelphia Eagles and Kansas City Chiefs, Pennsylvania Rep. Dwight Evans wagered Philly cheesesteaks against Missouri Rep. Emmanuel Cleaver’s KC barbecue.

Estes Kefauver was a football fan and proud alumnus of the University of Tennessee, so it’s no surprise that when his beloved Vols went to the Sugar Bowl in 1952, he made a bet on the outcome.

But that bowl game had ultimate implications well beyond the outcome of Kefauver’s wager. If you think that concerns about money ruining college sports, or about football driving conference realignment, are new phenomena – today’s article is for you.

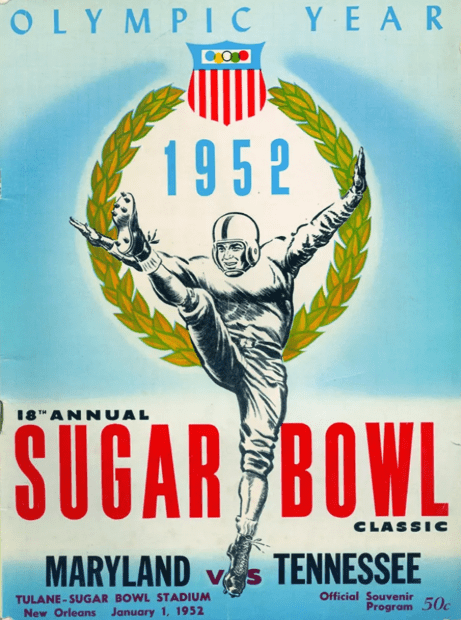

“The Second Game of the Century”

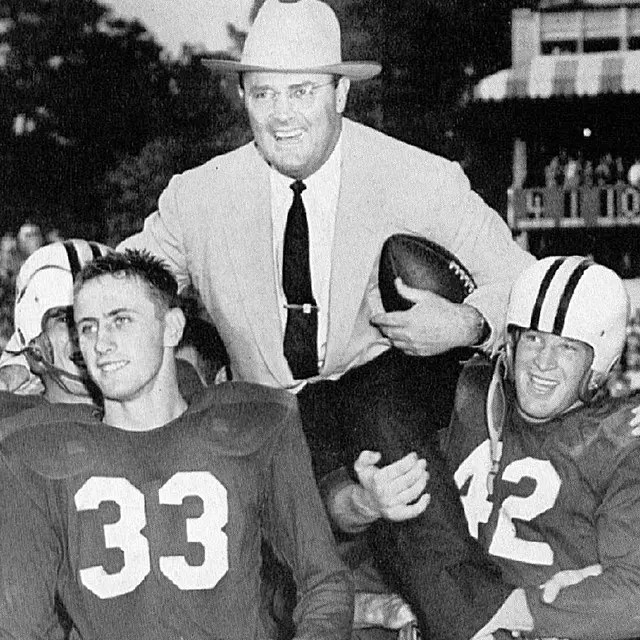

The 1952 Sugar Bowl was one of the most highly anticipated games in college football history. On one side, you had the top-ranked 10-0 Tennessee Volunteers, coached by Bob “The General” Neyland, a powerhouse team with five All-Americans on its squad. On the other side were the third-ranked 9-0 Maryland Terrapins, under the tutelage of coach Jim Tatum.

This was a matchup Tatum had coveted for a long time. He considered Neyland his coaching idol, and longed for the chance to show that his team could hang with the mighty Vols. He agreed to the Sugar Bowl matchup in mid-November, before the season was even over.

When the Maryland players indicated a desire to go to the Cotton Bowl– lured by the promise of free cowboy hats and boots for the winning team – Tatum promised to buy them all the hats they wanted if they agreed to the Sugar Bowl matchup instead.

When the Terps and Vols both finished the regular season undefeated (Tennessee winning the SEC and Maryland winning the Southern Conference), the Sugar Bowl became the de facto national championship. Sportswriters dubbed it the “second game of the century,” after the 1946 matchup between #1 Notre Dame and #2 Army that ended in a scoreless tie.

The game naturally became the subject of conversation between Kefauver and Maryland Senator Herbert O’Conor, who had become friends while serving together on the Senate’s organized crime subcommittee. O’Conor was a product of the University of Maryland system, having gotten his law degree at the university’s Baltimore campus, and he was excited for the Terps’ chances.

O’Conor proposed what he called a “friendly forfeit” to Kefauver. If the Vols won the Sugar Bowl, O’Conor promised to buy his Tennessee colleague a barrel of Chesapeake Bay oysters. Kefauver readily accepted the wager; in return, he promised that “if the impossible should happen” and the Terps should triumph, he would provide O’Conor with a live Tennessee raccoon.

Kefauver’s crack about the impossible happening wasn’t just boosterism. The Volunteers were seven-point favorites; their star player, tailback Hank Lauricella, was a New Orleans native eager for a chance to shine in front of his hometown fans.

The wager was on. And now all eyes turned to New Orleans, where the game would take place on New Year’s Day. And Kefauver would be there to cheer the Vols on in person.

A Big Easy Excursion Ends With A Big Upset

Not only was the Sugar Bowl an exciting game, but the Big Easy also represented a nice winter getaway, especially for Tennessee fans. Capitalizing on the state’s excitement, Nashville Tennessean publisher Silliman Evans chartered a special train to bring Vols rooters from Nashville to New Orleans for the game. Over 350 fans traveled on Evans’ train, including Kefauver and Governor Gordon Browning.

At the time, Tennesseans were also feeling a surge of excitement over the rumors that Kefauver might run for President. His backers had held a Kefauver-for-President extravaganza at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium just a couple weeks earlier, and speculation about Kefauver’s plans was reaching its peak. And so each one of the Tennessee fans on Evans’ train received a coonskin cap, allowing them to show support for their team and their home-state Senator simultaneously.

Upon arrival in New Orleans, Mayor deLesseps Morrison held a reception for Evans, Kefauver, and Browning. Morrison had been a strong supporter of Kefauver’s crime investigations, and was prepared to support his Presidential run.

“Tennessee has been in the limelight throughout 1951,” said Morrison. “First Sen. Estes Kefauver turned things upside down with his crime investigations and then the University of Tennessee football team took over and has been making history ever since. I hope you can start 1952 with a victory.”

Evans came bearing gifts for his host. He lent Morrison three antique swords that had belonged to Andrew Jackson and the Marquis de Lafayette for display in a local museum. He also presented the mayor with a 27-pound country ham.

Reporters asked Kefauver whether his appearance with a stealth kickoff to his Presidential campaign. He solemnly insisted that he hadn’t yet decided to run.

“I am not doing a thing about attracting nomination for the Presidency,” Kefauver stated. “I am not going to ask for help at this time, but if it’s decided that I am the candidate I certainly will get going.”

That didn’t stop his supporters from handing out “Kefauver for President” buttons at the governor’s mansion, or to everyone they met in the streets of New Orleans.

Unfortunately for the Tennessee contingent, the game didn’t unfold according to plan. Maryland took an early lead when running back Ed Fullerton scored to cap a 56-yard drive. After Lauricella fumbled the ensuing kickoff, the Terps had a short field, and made it 14-0 when Fullerton made a 6-yard pass for another TD.

Maryland led by as much as 21-0 before Tennessee finally scored, but Fullerton sealed the win with a pick-six interception return for a touchdown in the second half. The Terps wound up winning 28-13; fullback Ed Modzelewski, who rushed for 153 yards, was named the game’s MVP.

The game was a complete disaster for the Vols, whose mighty offense was completely bottle up by the Maryland defense. In addition to the fumble, Lauricella managed only a single rushing yard and threw three picks. Coach Neyland was so upset at the outcome that he refused to speak to reporters after the game.

The impossible had happened; Maryland had upset the Tennessee juggernaut. And it would soon be time for Kefauver to pay up.

Kefauver Pays His Forfeit

No sooner had the game finished than Kefauver was apparently trying to renegotiate the terms of the bet. Now he was offering to give O’Conor his treasured coonskin cap – the one from his 1948 election – instead of a live animal.

Kefauver claimed that he had actually had a live raccoon that had been donated by his supporters. But, he said, the animal had escaped from his car. “The coon thought Maryland didn’t have much of a chance,” he quipped.

O’Conor humorously insisted that Kefauver honor the original wager. “I await with lively anticipation the receipt of the coonskin cap,” the Maryland Senator told the AP. “I wonder if he’ll have much trouble catching the coon?”

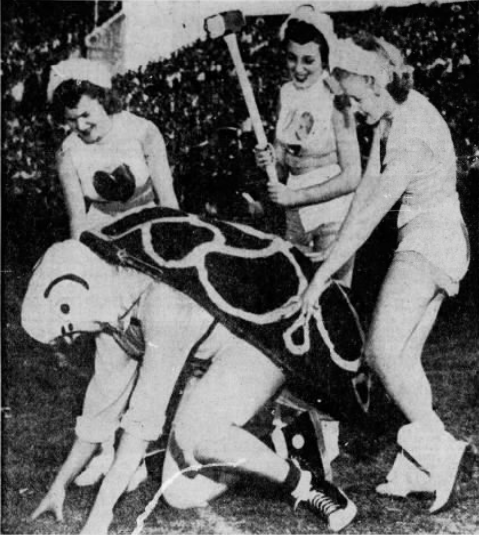

Kefauver held true to his word, and on January 7th – the Monday after the game – he presented his “forfeit” in front of the press. They’d originally planned to do the handoff in O’Conor’s office, but moved it to a meeting room to accommodate the large press contingent who turned out.

Kefauver reluctantly handed over his coonskin cap, along with the glass case in which he’d stored it and a scroll explaining the terms of the wager and acknowledging the defeat. After briefly donning the cap himself, the triumphant O’Conor handed it over to linebacker Dave Cianelli, one of the captains of the Maryland football team. Cianelli promised to display the cap in a place of honor on campus.

Alluding to his still-undeclared Presidential plans, Kefauver noted that “I may have to borrow it back someday.” Cianelli replied, “If you ever have the need for it again on the political battlefields, we’ll be glad to loan it to you.”

What happened next caused quite a stir. As the Chattanooga Times reported, Kefauver “donned a pair of heavy gloves and reached into a cage full of snarls and teeth to offer the chubby-cheeked Maryland senator a live coon from Tellico Plains.” O’Conor was less than thrilled about the prospect of handling a wild animal; he reared back and asked Kefauver to put the coon back in the cage.

O’Conor wasn’t the only reluctant participant in the exchange. According to the Times, “As Kefauver held him for the gaze of the motion picture and still cameras, the little [raccoon] quickly covered his eyes with the little paws to protect him from the frightful glare of the photographers’ lights.”

Kefauver did hold the raccoon long enough to calm him down to the point where O’Conor gave him a pet.

O’Conor donated the coon to the Baltimore zoo to be put on display. But there wasn’t anyone from the zoo present for the handoff; instead, O’Conor had an aide take the animal up to Baltimore on the train.

As the Baltimore Sun explained, it was a bit of a cloak-and-dagger operation:

Getting the raccoon to Baltimore in the railroad coach, where the transportation of live animals is prohibited, was accomplished by placing the animal in a cage and throwing a cover over it.

There wasn’t a peep out of the coon or the conductor.

A Landmark Game – In More Ways Than One

The 1952 Sugar Bowl was a remarkable game, and a monumental upset. But its long-term effects would be felt well beyond the season.

At the time, bowl games were still relatively novel, and they were a subject of controversy for some. The critics felt the bowls were too commercial and cheapened the integrity of the sport, in addition to promoting a winning-above-all attitude. The critics wanted to ban the bowl system entirely.

A number of those critics existed on the campuses of the Southern Conference, to which Maryland belonged. In September, the Southern Conference schools voted to ban their teams from participating in bowls.

Tatum, the Terps coach, refused to abide by this decision; he wanted his shot at mighty Tennessee. So he went ahead and agreed to play in the Sugar Bowl anyway, arguing that the conference’s decision shouldn’t have applied to a season already in progress. (Clemson, another Southern Conference team that played in that year’s Gator Bowl, felt similarly.)

The rest of the conference was outraged by Maryland’s and Clemson’s defiance of the decision; they responded by suspending both teams from conference play for the entirety of the 1952 season.

But neither team took the decision lying down – and neither did some of their fellow schools, who felt they might want to play in a bowl someday. The following year, seven of the Southern Conference schools – along with Virginia, a former SoCon school that had gone independent – agreed to form the Atlantic Coast Conference, which exists to this day. (So does the Southern Conference, although it now competes at the FCS level, a level below the ACC and SEC.)

The formation of the ACC demonstrated that in the end, money and glamor triumphed over old conference allegiances. (That’s proven true repeatedly throughout the history of college sports.)

And of course, the Sugar Bowl wasn’t the only loss Kefauver and Tennessee would suffer in 1952. But that’s another story.

Leave a comment