Tennessee has long been a musical state. Nashville, of course, is famously the capital of country music. But the Volunteer State also has lengthy traditions of bluegrass, hillbilly music, jazz, blues, gospel, and other genres that fall under the general umbrella of “old-time music.” (Not to mention Elvis Presley!)

Throughout the 20th century, politicians – especially Southern ones – have sought to associate themselves with music as a way of connecting with the people. And given Tennessee’s strong musical traditions, any smart politician representing the state would seek to get some of the state’s many talented musicians on his side.

Estes Kefauver was a smart politician. Throughout his political career, he made use of country, bluegrass, and hillbilly artists as part of his outreach to voters. His relationship with those artists emphasized his Southern roots and marked him as a man of the people. And particularly in his home state, Kefauver’s association with popular musical stars probably helped him connect with constituents whose own views were more conservative than his own.

(In this article, I am deeply indebted to Peter La Chapelle’s fantastic book I’d Fight the World: A Political History of Old-Time, Hillbilly, and Country Music. If you’d like to know more about how country has been used by politicians throughout American history – and to better understand a lot of culture-war controversies around country today – I strongly urge you to read La Chapelle’s book.)

A Harmonious Beginning

When Kefauver first ran for the Senate in 1948, he had the power of musical stardom working against him. Not in his opponent, B. Carroll Reece, a former Congressman and current RNC chair with no known musical talents. But there was also a gubernatorial race that year, and the Republican candidate was country music legend Roy Acuff. Reece and Acuff campaigned together, and the performances of Acuff and his Smoky Mountain Boys were the highlight of these events.

Acuff’s rallies drew big crowds, enough to give the Democrats worry that the GOP might pull an upset. Neither Kefauver nor Democratic gubernatorial candidate Gordon Browning was a musician, but Kefauver hired bluegrass musician Curly Seckler and his Country Boys to play at his rally in Selmer. Seckler wasn’t nearly as famous as Acuff, but he was no slouch; he would join Flatt and Scruggs’ Foggy Mountain Boys the following year.

Kefauver had no trouble rolling to victory over Reece and joining the Senate.

Once in office, Kefauver kept up his country connections. He appeared regularly on the Bristol-based radio show “Farm and Fun Time,” hosting a segment called “In Your Senator’s Office.” The program, which featured a combination of bluegrass music and farming news, was popular with rural audiences in East Tennessee, and allowed Kefauver to remain in touch with voters there.

But Kefauver’s musical affiliations really took off when he ran for President in 1952.

A Presidential Hoedown?

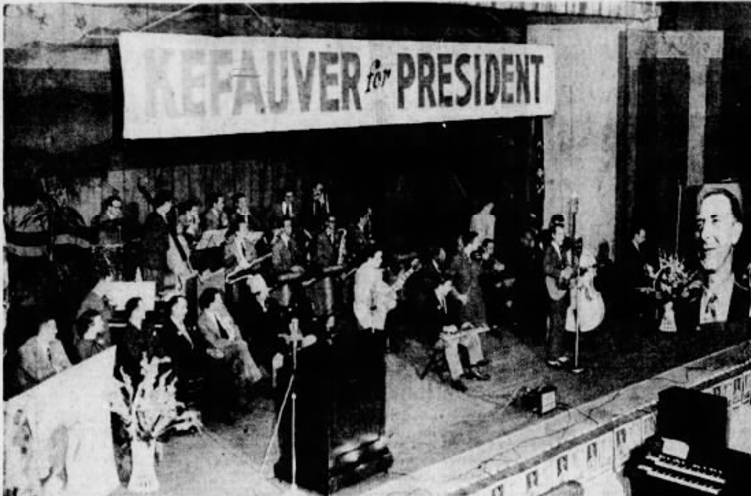

If you wanted to put on a spectacle in Tennessee in the 1950s, there was no better place to do it than at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, home of the Grand Ole Opry. And when Kefauver’s friends and allies wanted to promote his Presidential candidacy, they did it with an unofficial campaign kickoff event at the Ryman in December 1951. (The candidate himself, who had not yet declared his intention to run, skipped the event – he was on a listening tour of the state at the time.)

The Kefauver-for-President evident was a country music spectacular, featuring a hit parade of Grand Ole Opry regulars. Hillbilly comedienne and Tennessee native Minnie Pearl performed a skit that delighted the audience. Musical acts included Karl Garvin and his jazz orchestra (who played a rousing round of “Dixie,” drawing rebel yells from the crowd), Opry regular George Morgan and the Candy Kisses Kids, electric organist Jimmy Richardson, and the Dinning Brothers, who performed the novelty “Senator from Tennessee” in honor of his organized crime investigation.

The speakers continued the populist theme established by the entertainment, tabbing Kefauver as the people’s champion with the courage and strength to clean up the mess in Washington.

Albert Gore, who would be elected to the Senate himself that fall, was the primary speaker. He proudly proclaimed that “nothing wrong with the Democratic Party that cannot be cured by the Presidential nomination of Estes Kefauver.”

He added that Kefauver had “challenged the imagination and won the affection of the American people like no one since the advent of Franklin Roosevelt” and said that he would clean the party of the “human parasites, chiselers, cheaters and influence peddlers” that he said were clinging to the party like barnacles to the hull of a ship.

State Democratic party chairman Jack Norman likened Kefauver to a modern-day Andrew Jackson, the perfect tonic for an American public “disturbed with professional politicians on both sides and irritated with instability and immorality in public service.”

Norman said the voters “are acclaiming [Kefauver] as a leader of the people and not as the anointed son of a political clique. He represents their free choice. He is their popular nominee.” He predicted that come next year, “The people are going to take this thing into their own hands, walk into an open convention and make him our leader.” (This, more than anything Kefauver actually said, is the kind of rhetoric that probably made party leaders fear he would be a demagogue.)

In keeping with the theme, students from nearby Cumberland University presented a giant mop, which they said Kefauver could use to “sweep the government clean.”

Once Kefauver did throw his hat into the ring, country musicians began recording songs in his honor. Larry Dean and the Virginia Playboys recorded “Estes in Bestes,” their “Kefauver for President fight song” that hailed him as a “crime-bustin’” folk hero. The same year, Dinah Shore and Tex Williams recorded their cover of “Senator from Tennessee,” which didn’t chart but spoke to Kefauver’s national reputation.

Kefauver also made musical acts a regular feature at his campaign events. When stumping in his home state, he invited Pearl and Morgan to campaign for him, along with songwriter Hank Fort.

In other states, he hired country and western swing bands who were known locally. For instance, at the Oklahoma State Picnic in Los Angeles (an annual event for Okies who had transplanted to Southern California), Kefauver was the featured speaker, appearing with “Western stars of stage and television.”

As it turned out, all the songs and country stars in the world weren’t enough to soften the hearts of party bosses, who snubbed Kefauver at the convention in favor of Adlai Stevenson.

Stevenson’s Mississippi Misadventure

You would think that Stevenson wasn’t much of a country guy, and you would be right. That didn’t stop him from trying to connect with a country audience – with disastrous results.

In 1954, Stevenson spoke at the end of a National Hillbilly Music Day festival in Meridian, Mississippi. His speech was expected to be both short and apolitical, but Stevenson evidently didn’t get the message. He spoke for 45 minutes, tearing into President Eisenhower and Joseph McCarthy and making only a brief mention of his supposed love of hillbilly music and Jimmie Rodgers (who was being honored at the festival).

Stevenson was attacked for ruining a supposedly nonpartisan event, and the Country Music Disc Jockey Association issued a statement condemning the festival for inviting him. (Stevenson didn’t help matters when he was asked is he had “ever considered campaigning with a hillbilly band.” His response: “No, I’m not equipped for it… I’m tone deaf.”)

Kefauver Goes Country Again in ’56

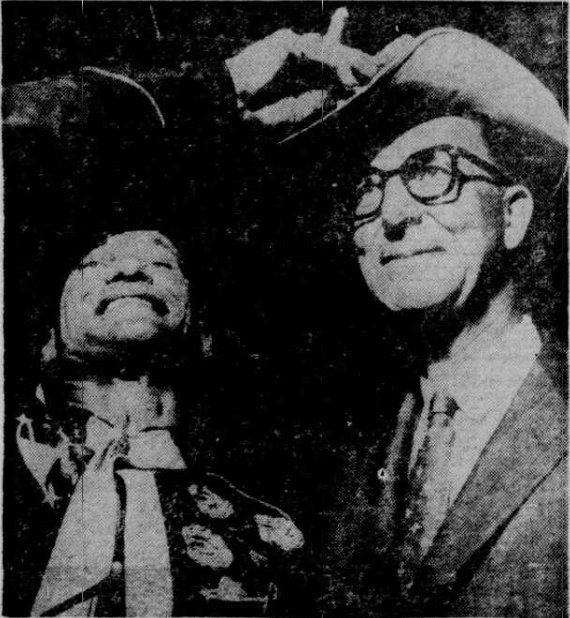

Kefauver went back to the country well during his second run in 1956, with the same result. However, perhaps the most notorious country musician associated with that election was one Cowboy Brown.

Writing about the Florida primary for the New York Times Magazine, E.W. Kenworthy zeroed in Brown, who sounds like quite the colorful character. Kenworthy noted that Brown possessed “at least forty fancy shirts” and “has a way of always turning up when there’s campaigning afoot” (which was a nice way of calling him a publicity hound).

When Kefauver was campaigning in Tampa, Brown and his band showed up in “an old sedan equipped with a loudspeaker” and led the campaign caravan “with his horns blaring the Kefauver hill-billy song (‘Kefauver! Kefauver! Kefauver is the name!’)”.

But when Stevenson campaigned in Orlando a couple weeks later, Brown showed up at his hotel, ready to do the same thing. Upon sight of Brown and his fancy shirt, Stevenson blinked in amazement and exclaimed, “Good heavens, when did I pick me up a cowboy?”

Kefauver also had a song composed in his honor this time around, although this one was less flattering and not released on a record. Watch Kefauver tromping exhaustedly through the Sunshine State looking for every possible hand to shake, New York Herald Tribune correspondent Earl Mazo penned a parody of the traditional ballad “Sweet Betsy from Pike” about Kefauver:

I’m Estes Kefauver from old Tennessee,

And all that I want is the Presidency

The bosses despise me all over the land,

That’s how they made Cme a handshakin’ man

By the time Kefauver was selected as Stevenson’s running mate at the convention, his signature song had become “The Tennessee Waltz,” which was played at virtually every campaign stop to the point that he, his campaign staff, and the press corps were all thoroughly sick of it. (Although not as sick as they would be when Eisenhower crushed the Stevenson-Kefauver ticket in November.)

Here Comes Goodbye

For Kefauver’s final Senatorial campaign in 1960, he turned to the Grand Ole Opry again for help. This time, country stars Hank Snow and Billy Grammer.

The latter’s appearance with Kefauver at an event in Jefferson City in late July generated some controversy when the anti-Kefauver Nashville Banner ran a story claiming that Grammer’s appearance was being paid for by music licensing organization BMI, and that he was appearing at a discount rate in hopes of drumming up crowd for Kefauver.

Grammer denied the charges in an interview with the Nashville Tennessean, saying that he and his Gotta Travel On Boys were appearing on their own dime “because I believe in this man… I am up here as a young voter myself. It is a personal thing.” He added that he had not coordinated his appearance with Kefauver’s campaign and said that Kefauver “doesn’t need a crowd gatherer. The crowds are coming out to hear him.”

Up until his untimely death in 1963, Kefauver remained connected to country through his relationship with the Country Music Association, the industry’s trade association. La Chappelle noted that “by the early 1960s, [Kefauver] was the CMA’s point man for copyright legislation and for ensuring passage of a national ‘Country Music Week’ resolution each year in the Senate.”

In the final weeks of his life, Kefauver tried to get President Kennedy to issue a presidential proclamation honoring Country Music Week. Kennedy declined, and the genre wouldn’t get a Presidential nod until Richard Nixon declared October to be County Music Month in 1970.

Postscript: Just Plain Folks

I have no idea whether Kefauver was really into country music. Given his background and upbringing, it’s certainly possible that he was a genuine fan of the genre, but it’s also possible that he recognized the political advantage of hitching his wagon to that particular post.

For that matter, it’s far from clear whether most of the artists above were genuinely fans of Kefauver, or if they just hoped to capitalize on his fame. After all, many of the same folks – including Pearl, Snow, and Grammer – all campaigned for George Wallace a few years later.

But whether the relationship between Kefauver and country was transactional or genuine, it was savvy. Kefauver may or may not have liked country music, but he knew that his supporters – the “little people” in rural and farm areas who the professional politicians looked down on– did.

Kefauver’s embrace of country music symbolized his embrace of the people who loved it. And that embrace – that basic, deep respect for the average man and woman – might just have explained the deep well of popular affection for Kefauver that so mystified the press. You might say he was singing their song.

Leave a comment