The 2024 election, which gave the GOP unified control of the government, has left despondent Democrats asking themselves: What do we do now?

For those seeking a way forward, I present Senator Stephen M. Young of Ohio.

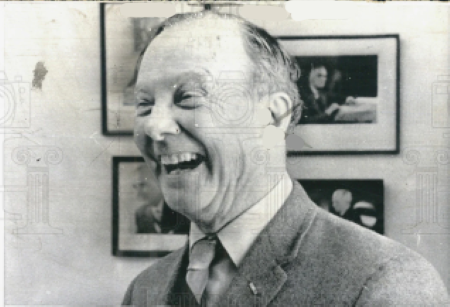

After a long and bumpy political career, Young was elected to the Senate and spent two terms as a real-life version of Warren Beatty’s character in “Bulworth”: he fought for the poor and working class and spoke his mind, never caring what people might think, and he didn’t hesitate to tell his opponents that he considered them cruel, stupid, or ignorant. Democrats looking for a way forward could do worse than to learn from Young’s example.

Born to Serve – and Born to Fight

Young credited his father, a county judge, for instilling liberal beliefs in him. Those beliefs only sharpened due to things he saw as a boy. He vividly recalled watching a town police officer beat a homeless man for the “crime” of sitting on a bench. This experience left him with a lifelong sympathy for the poor and struggling, and a mistrust of authorities who used their power to punish the poor.

Young quickly grew interested in politics, getting elected to the Ohio state House of Representatives in 1913 at age 24 and serving two terms, beginning a lengthy career in public service.

Young served on the battlefield as well, fighting in both World Wars. During World War II, he won a Bronze Star and four battle stars in the European and North African theaters, including a stint as the Allied Military Governor of Italy’s Reggio Emilia province.

Despite his early start, Young was no electoral wunderkind. He served four terms in the U.S. House, but in three different stints between 1932 and 1950. He ran twice for governor and twice for Ohio attorney general and lost all four races.

Young Enters a Hopeless Race – and Wins

In 1958, Young was 69. A lot of men his age would contemplate retirement, but he decided to take one more shot at elected office. This race was perhaps his longest shot yet.

John Bricker (the same guy who authored the Bricker Amendment covered here last week) was a two-term incumbent Senate, a three-term governor, and had been GOP candidate for Vice President in 1944. He was hugely popular in Ohio and considered electorally invincible. Although he had become extremely conservative, going against him seemed like a doomed endeavor.

Young didn’t care. “To be perfectly honest, the initiative to run came from me,” he wrote in his 1964 book Tales Out of Congress. “And what motivated me was the thought of John W. Bricker going back to the Senate to represent the people of my state. Bricker’s voting record was deplorable… And so I thought it might be something of a public service to the citizens of Ohio to show how they were being misrepresented.”

Accordingly, Young filed for the Democratic nomination, which he won by default. (Prominent Ohio Democrats tried a couple times to get Young to drop out in favor of someone they thought would have a better shot at winning. Young told all comers: I’m staying in. If your guy wants to join the primary and try to beat me, have at it. No one did.)

No one gave Young a chance against Bricker. As he wrote, “The politicians had thought I had as much chance of getting into the Senate as Grandma Moses had of becoming Miss America.” Only one newspaper in the state endorsed him. The national Democratic party provided only nominal support and refused to give his campaign funds. Even Ohio’s sitting Democratic Senator, Frank Lausche, declined to campaign for him.

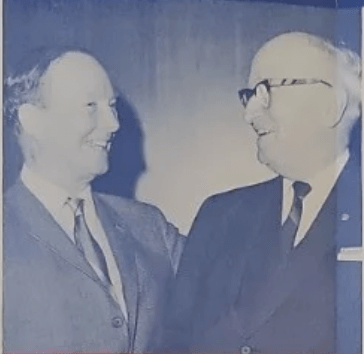

Young campaigned across the state, blasting Bricker as “the darling of the reactionaries,” but his chances looked grim. Finally, he caught a break when former President Harry Truman announced he would travel the country to stump for Democratic candidates. Young paid out of his own pocket to reserve a hall in Akron for Truman.

The feisty ex-President took a shine to Young and made several stops with him across Ohio, also recording radio and TV sports on his behalf. Truman also persuaded the national Democrats to send some money Young’s way. His full-throated endorsement gave Young a much-needed boost.

Young also benefitted from the fact that Republicans placed an anti-union “right to work” amendment to the state constitution on the ballot. Bricker supported the amendment, but knew it would be controversial in union-heavy Ohio and tried unsuccessfully to get the Republicans to pull it off the ballot. Young ran hard against the amendment, stirring up sentiment in union households.

When all was said and done, Young stunned Bricker by over 150,000 votes.

A “Peppery” Maverick Who Pulls No Punches

Right away, Young blazed his own trail. Even before taking office, he announced that he would sell his stocks, to avoid any conflict of interest in his Senatorial duties. (Bricker’s law firm represented the Pennsylvania Railroad, and he had infamously voted in the railroad’s interess on several occasions.)

Young made clear that he would not allow his favors to be purchased – with perhaps one minor exception. “I don’t accept gifts of more than $5 in value,” he said. “But every bottle of liquor, I assess at $4.99.”

Young also opted out of the Senate tradition in which newly elected members were escorted by their fellow home-state Senator to be sworn in. Noting Lausche’s indifference to his campaign, Young said tartly, “I’ve made it this far without his support, I guess I can make it the rest of the way on my own, too.” He added, “If Senator Lausche supported me for election, it was a well-guarded secret.”

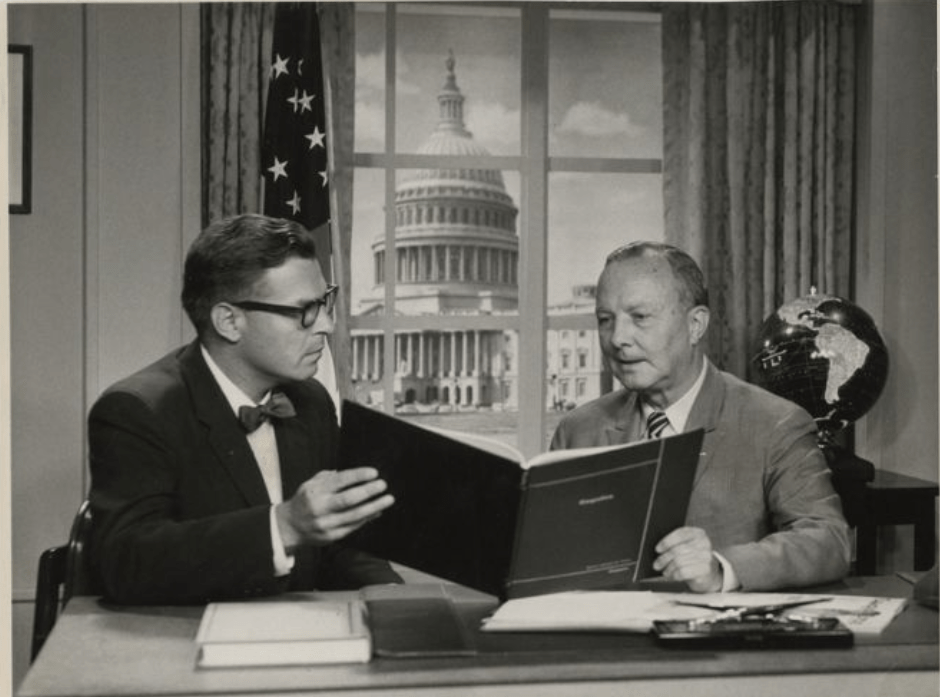

During his first term, Young generally followed the liberal line in voting, and was not known for sponsoring any major bills. (In 1963, he voted in favor of the limited nuclear test ban treaty with the Soviet Union, a vote he called the most important of his career.) What made him famous was his delightfully blunt language, both in his speeches and his correspondence.

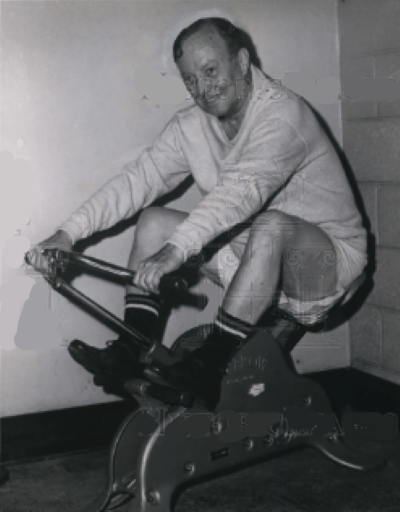

Young’s letters to constituents were justly legendary. He had no patience for writers he considered rude, ignorant, or nasty, and he hit his critics as hard as he hit the punching bag at the Senate gym, where he exercised daily.

Once, Young replied to a hostile letter by saying, “Dear Sir: It appears to me that you have been grossly misinformed, or are exceedingly stupid. Which is it?”

Another time, he received a letter from a constituent who had voted for him, but was extremely disappointed by his performance in office. Young blithely wrote back, “You are entirely misinformed and your letter is silly, but thank you for voting for me.”

A favorite tactic was to mail the original letter back to the sender with a note stating, “I am sending you a letter received this morning, evidently from some crackpot who used your name.”

Young generally considered brevity the soul of wit. A voter once sent him a long and angry letter and included his phone number, saying, “I would welcome the opportunity to have intercourse with you.” Young replied, “You sir, may have intercourse with yourself.” When someone accused Young of being the sort of person who would enjoy desecrating graves in Arlington National Cemetery, his reply read in its entirety: “Sir, You are a liar.”

However, on occasion he gave a lengthier reply when he felt it was deserved. Upon reading that Young was speaking to a left-wing group, the Hamilton County chapter of the American Legion passed a resolution “disapproving and censuring” Young and demanding that he cancel the speech. The group’s Americanism Chairman sent Young the resolution; in response, the Senator blasted him and the chapter.

So – you self-appointed censors and self-proclaimed super-duper 100 percent America Firsters censure me. You professional veterans who proclaim your vainglorious chauvinism have the effrontery to issue a press release gratuitously offering an expression of censure and making urgent demand that I cancel a speaking engagement previously made.

I repudiate your resolution, Buster, and your pompous, self-righteous, holier-than-thou title of Americanism Chairman! Why don’t you read and try to understand that cornerstone of our liberties, the Constitution of the United States?

When Ohio Rep. Gordon Scherer supported the Legion’s resolution, Young dismissed him with the withering retort: “While I was on the Anzio beachhead, [Scherer] was Safety Director of Cincinnati, Ohio.”

Young took great pride in his poison-pen replies. He reprinted several of them in Tales Out of Congress. His 1964 re-election brochure stated, “Peppery Steve Young has a nation-wide reputation for his straight-from the-shoulder answers.” When asked to justify these letters, he simply said, “Every man has a right to answer back when being bullied.”

Young’s pungent phrases weren’t confined to his correspondence, either. On the Senate floor in April 1961, he delivered a scathing condemnation of the far-right John Birch Society.

“I assert the John Birch Society is a Fascist group,” Young said. “It is well larded with rightwing crackpots. It is an ideological abomination, and the self-appointed vigilantes who are its leaders deserve the disdain and scorn of every American who values his democratic heritage.”

He denounced Birch Society found Robert Welch, Jr. as a “little Hitler” and called Welch’s Blue Book “a psychotic collection of hate, slander and demagoguery.”

He correctly likened the Birchers to the anti-immigrant Know-Nothing movement of the 1850s and predicted that, like the Know-Nothings, the Birchers “will pass away unwept, unhonored, and unsung.”

Despite his fierce condemnation of the Birchers and their beliefs, Young defended their right to free speech and expression. “Without a doubt, it is legal for a man to be a Fascist – if he wishes to be that stupid – and to express opinions no matter how distorted, fantastic, and extreme they may be,” Young said, adding that “any mercenary demagog has a right to express his opinions though distorted, unfounded, and false.”

One Ohioan wrote to demand that Young retract his statements about the Birchers. Young’s reply, in its entirety: “Sir: No.”

Another Long-Shot Race, Another Shocking Victory

It was uncertain whether the 75-year-old Young would seek re-election. Several Senate colleagues saluted him at a testimonial dinner in Cleveland in September 1963. Truman was the featured speaker and called Young his “favorite senator.”

President John F. Kennedy sent a recorded message, praising Young for his service and his vote for the test ban treaty. Kennedy’s handwritten notes on his script, however, revealed more complex feelings about the maverick senator. The original script read, “Senator Young’s political philosophy is consistent with my own.” Kennedy crossed out “consistent with my own” and wrote “in the great tradition of the Democratic Party.”

Kennedy also crossed out his planned closing sentence: “Steve, we want you back in 1964.”

Despite Kennedy’s apparent ambivalence, Young did run for a second term. This time, he drew a primary opponent: astronaut John Glenn. That might have been a tough test, but Glenn withdrew after suffering a fall in his home.

In the general election, Young faced Rep. Robert Taft Jr., scion of the Taft political dynasty. Despite his incumbency, Young was considered the underdog. “Ohio Republicans figure to send another Senator Taft to Washington next year,” wrote Time magazine, treating Young as an afterthought. The New York Times, meanwhile, described Taft as “a proved [sic] vote-getter with a name considered magic in this state.” The Cleveland Plain Dealer ran its endorsement of Taft on the front page.

On Election Day, however, Young squeaked past Taft by fewer than 16,000 votes out of almost 4,000,000 cast to receive a second term. The Times called it “one of the most stunning upsets among the country’s senatorial contests.” The man Time called “a happy specialist in lost causes and a certified political eccentric” would serve another six years.

The Veteran Comes Out Against the War

Shortly after securing reelection, Young took a surprising stance that separated him from many of his fellow Democrats. In October 1965, he went on a congressional trip to South Vietnam. While there, Young noticed several things that contradicted the administration line.

Most shockingly, he claimed that a CIA operative told him that a special CIA force had disguised themselves as Viet Cong soldiers, murdering villagers and raping women. In response, the outraged CIA and the State Department both tried to silence him. Young later said he wasn’t sure if the worst allegations were true, but stood by his belief that the CIA’s activities in Vietnam were wrong. (Given the revelations of the Church Committee in the ‘70s, Young’s initial statements may well have been accurate.)

Young became one of the first Senators to call for US withdrawal from Vietnam. His bold, uncompromising stance earned him the admiration of young antiwar activists – even if they didn’t quite know what to make of him.

In 1966, Young spoke to an antiwar forum at Harvard. James Lardner, who wrote it u[ for the Harvard Crimson, found Young perplexing. Lardner wrote that the forum’s organizers “probably figured that such an unequivocal opponent of administration policy had to be both radical and swinging, but Young – who defies quite a few dove stereotypes – is neither.”

“What is hard to figure about Young is just what in his blood count motivated him to take a stand so repugnant to his Senate colleagues and–most likely–to his constituents as well,” wrote Lardner. “There is something of the traditional midwestern isolationist in him, but he is clearly more than that. His progressivism is evidenced by his votes on domestic questions, and, while hardly a leftist, Young has a leftist’s distrust for the military.”

Nor did Young stick to college campuses. The month before his Harvard appearance, he advocated American withdrawal from Vietnam to the City Club of Cleveland.

His stance attracted support from around the country. Young said that his letters from Ohio ran 5-to-1 in favor of his stance on Vietnam, while the letters from around the country were 20-to-1 in favor.

In response to a Washington State woman who wrote in 1967 to thank him for opposing the war, he wrote, “We should never back down in expressing our views and denouncing outrageous insinuations that dissent and disagreement over President Johnson involving us in a civil war in Vietnam is disloyalty. I repudiate such assertions.”

To critics, Young replied with his usual brand of acidic scorn. One writer accused him of trying to deceive voters on the war and added indignantly, “What kind of fool do you think I am?” Young’s response: “In your letter you ask what sort of fool I think you are. Am not interested in cataloging you.”

After the tragedy at Kent State in which National Guard troops shot and killed four students, Young argued that the student’s families should receive $5 million apiece. One Ohioan wrote to him arguing that the Guard did the right thing. Young shot back, “Only a cruel ignoramus would take the position that those four students – not one of whom was rioting or throwing stones – deserved to be killed. Also, you are a stupid, cruel jerk.”

Young Does Not Go Gentle into That Good Night

In early 1970, Young decided not to try for a third term. His statement announcing his decision was filled with his characteristic feisty spirit. He bragged that he had “not missed one day from Senate duties due to illness, either in attendance of Senate session or at my Senate office or committee meetings.” He noted that he enjoyed the job, and said, “I feel I could continue to represent Ohio and the nation with the same fidelity, zeal and great industry as I have since January 1959.”

But his age, he said, led him to decline another campaign. “In the spirit of our young nation,” he stated. “I believe a man my age should pass on opportunity to a younger man who is under 65 years of age.” Young was 81 when he said this.

“My years in the Senate could be termed golden years,” Young said. “They have formed a moving and thrilling chapter of my life.”

Young’s former campaign manager, Howard Metzenbaum, won the Democratic primary to succeed Young; however, he lost to Taft Jr. in the general election. Young returned to practicing law in Cleveland and Washington and kept kicking until he died in 1984 at age 95. The Washington Post’s obituary noted his “reputation as one of the more zesty and strong-minded men to serve on Capitol Hill.” They weren’t kidding.

A Plainspoken Working Class Fighter to Emulate

As the Democrats decide how to modify their message going forward, they should remember Stephen Young.

Young devoted his career to fighting for the poor and working class. As he said in his 1964 campaign brochure: “The acid test of a civilization is its ability to see to it that every man, woman and child has the opportunity to live with dignity in decent surroundings.” He didn’t have to convince the people he fought for that he really cared about them; he showed it with his votes and actions. Even his detractors acknowledged his support for the common man.

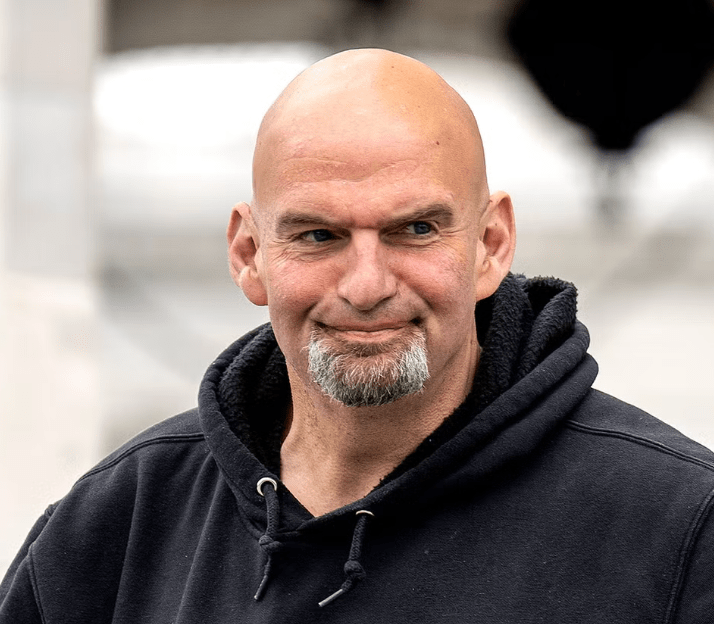

His blunt, straightforward language would arguably work even better today. His constituent letters were controversial but earned him a reputation as a fighter. How much more famous would a politician like Young be in today’s social media world? (Sen. John Fetterman of Pennsylvania has taken a page from Young’s playbook.)

Sadly, Young’s story has largely been lost to time. But if Democrats want to regain some of the ground they’ve lost with working-class voters, they’d do well to revive his memory – and follow his example.

Leave a comment