Estes Kefauver died in August 1963, which that he missed many of the major events of the 1960s. He wasn’t around to vote on the Civil Rights Act of 1964 or the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He wasn’t around for the social unrest and the divisive election of 1968. And he was not around for the debate over America’s involvement in Vietnam.

We can’t know for certain how Kefauver would have reacted to those situations, but we can make some reasonable guesses based on his track record. Given his record on civil rights, as well as the fact that he was moving in a more pro-integration direction with time, he likely would have supported the 1964 and 1965 Acts.

As for Vietnam, we can look at his record on another debate over American involvement in a conflict in Southeast Asia with the goal of containing the spread of Communism. With that in mind, let’s review Kefauver’s reaction to the Formosa conflict of the mid-1950s.

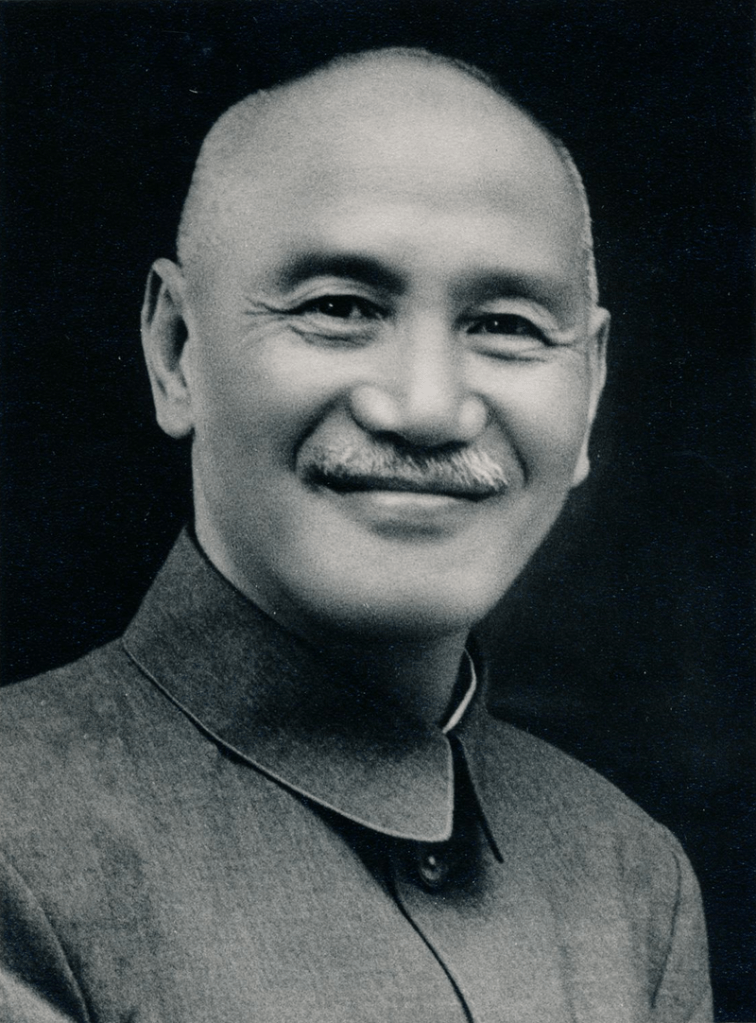

After Chiang Kai-Shek was defeated by the Communists in the Chinese Civil War, he and his Nationalist forces decamped to the island of Formosa (known today as Taiwan). The US sided with Chiang and the Nationalists, considering them the true government of China, but Harry Truman refused to provide them with any military aid (at least until the Korean War broke out, at which point he sent the Seventh Fleet down to the Taiwan Strait to prevent any funny business).

When Dwight Eisenhower entered the White House, he moved the Seventh Fleet out of the Strait. This emboldened the Nationalists, who quickly started making noises about launching an attack to reclaim the Chinese mainland.

After several months of escalating tensions in the summer of 1954, the Nationalists escalated the situation dramatically by placing over 70,000 troops on the islands of Quemoy and Matsu, both of which were directly off the coast of the Chinese mainland. In response, the Communists began shelling the islands, and Premier Zhou Enlai started making noises about “liberating” Formosa (that is, bringing it under Communist control). He also dispatched troops to the area.

The Nationalists appealed to the US for help, and Eisenhower was inclined to give it to them. He asked Congress for what amounted to a blank check to address the situation.

Eisenhower signed a mutual defense treaty with the Nationalists to defend Formosa and the nearby Pescadores Islands if they came under attack. (Notably, this treaty did not include Quemoy and Matsu.) In addition to requesting Senate ratification of the treaty, he requested Congressional authorization to use American armed forces to defend Formosa, the Pescadores, and any “related positions and territories” held by the Nationalists. The “related positions and territories” were left vague – deliberately, critics charged, to give Eisenhower the opportunity to include Quemoy and Matsu in the list.

Kefauver was thoroughly opposed to the whole idea. Although he was on board with the principle of limiting the spread of Communism, he didn’t want the American military getting involved in the Chinese conflict. He didn’t think Chiang’s Nationalists had any particular claim to Quemoy or Matsu, which he viewed as part of the territory of mainland China. And he distrusted Chiang’s motives, believing that he was seeking a pretext to drag the US into helping the Nationalists invade mainland China.

Instead of military intervention, Kefauver favored a diplomatic solution, in which the United States would consider granting diplomatic recognition of Communist China in exchange for lasting resolutions of the conflicts in Formosa and Korea.

Kefauver was one of the leading voices against American military action in the Taiwan Strait. The problem was that he had precious few allies in this fight. A handful of Senate liberals – Hubert Humphrey, Wayne Morse of Oregon, New York’s Herbert Lehman, Kefauver’s Tennessee colleague Albert Gore –were similarly wary of American involvement, but there weren’t nearly enough of them to vote down Eisenhower’s proposed resolution. That didn’t stop Kefauver from doing whatever he could to slow down what seemed to him like a runaway train.

Kefauver warned that the administration’s bellicose rhetoric over the situation in the Taiwan Strait might lead to war with China. “That the United States should be plunged into war over Matsu and Quemoy ought to be unthinkable,” said Kefauver. “Yet there are those in high places who are plotting to bring such a war about, whatever the risk.”

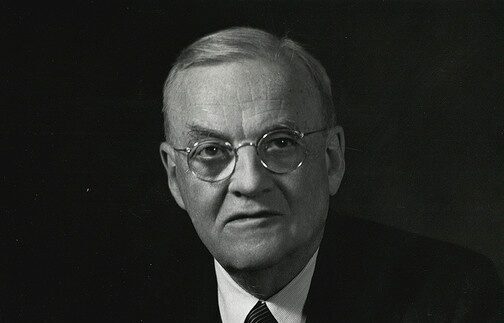

Kefauver’s alarm at the situation only grew when Secretary of State John Foster Dulles began talking openly about the possibility of using nuclear weapons against China.

Although he recognized that there was little hope of convincing his Senate colleagues to vote against Eisenhower’s Formosa resolution, he urged that the Senate work to “get the resolution in such shape that it will result in the least possible chance of war, and still maintain our honor.”

He proceeded to propose several solutions toward that end. His first hope was to get the United Nations to protect Formosa. He proposed an amendment to the resolution before the Foreign Relations Committee, which would have turned the defense of Formosa and its other islands over to the UN. The committee voted his amendment down 20-8. (It didn’t help that the UN had already indicated that it had no interest in getting involved.)

After that failed and the Foreign Relations Committee reported the resolution to the full Senate, Kefauver switched tactics. This time, he backed Humphrey’s amendment explicitly limiting the authorization of force to defending Formosa and the Pescadores Islands – specifically excluding Quemoy and Matsu. He argued that the was “no moral basis whatsoever for keeping the United States’ position cloudy in so far as Quemoy and Matsu are concerned.” This amendment was defeated 75-11.

After the amendments failed, Kefauver voted reluctantly in favor of the resolution to authorize military force, which passed 85-3. He acknowledged that “[i]t is difficult to resist a presidential request of this kind.” However, he stated his belief that “a great many senators are with us in their hearts” in having reservations, despite having voted for the resolution.

When Eisenhower’s Mutual Security Treaty with Formosa came up for approval the following month, the Senate ratified it by a vote of 64-6. Kefauver was one of the six who voted against it. While he was willing to grant Eisenhower the authority to use military force to address the current crisis, he opposed making a permanent commitment to defend Formosa – and, by extension, the Nationalists.

“I am not in favor of tying our future to the future of Chiang Kai-shek,” he said. “His motives and aims are different than ours… I am afraid his ambition to invade the mainland, while ours is to preserve the peace, enhances the chance of dragging us into war,” Kefauver said.

Kefauver’s vote against the treaty – along with the “no” vote of his colleague Gore – angered one Tennessee chapter of the American Legion, which passed a resolution calling for the state’s nickname to change from “The Volunteer State” to “The Slacker State.”

In response, Kefauver said, “I always welcome criticism, favorable or otherwise, whether it is motivated by a reasonable belief that I am wrong or by sheer malice or ignorance.” However, he objected to the “Slacker State” designation, saying that it dishonored “the countless thousands of loyal, patriotic Tennesseans who have given their lives in defense of our Country, as [well as] the widows and orphans they left behind.”

Kefauver remained highly critical of the administration’s handling of the conflict. In late March 1955, he gave a major floor speech again accusing the administration of trying to drag the country into war. He charged that the administration “must know that the vast majority of the American people are against them. The mood of America, no matter how warlike some of our leaders wish to make us seem, is deeply pacific; and, as a matter of fact, we know that we are not going to have any allies, or substantial allies, if we get into a war over Quemoy and Matsu.”

Kefauver’s critique earned him a personal rebuke from the ever-obnoxious Joseph McCarthy.

“I thought we had seen the last of the Chamberlain tradition when the Acheson-Marshall-Truman cabal was voted out of power,” said McCarthy, deploying his usual tact. “I thought we had seen the last of appeasement, retreat, and surrender. But the spirit of Neville Chamberlain – of Munich – is evidently very much alive. The Senator from Tennessee has proved himself a most worthy heir of the Munich tradition.”

In response, Kefauver said that he was “not surprised” to see McCarthy engage in his usual tactics of “call[ing] names” and “try[ing] to make odious comparisons.” However, he quipped that unlike Chamberlain, “I have never owned an umbrella.”

At any rate, the Formosa crisis managed to resolve itself without turning into a war. In April 1955, Zhou Enlai announced a willingness to negotiate with the US; the following month, his army stopped shelling Quemoy and Matsu. The Eisenhower administration touted this as a victory for deterrence and nuclear brinksmanship. Some historians agree, arguing that the Communists back down because the Soviets were unwilling to threaten a nuclear response if the US bombed China.

However, the victory – such as it was – didn’t last. The negotiations failed to address the underlying causes of the conflict, and another crisis bubbled up three years later. Also, the nuclear saber-rattling from Dulles and the Americans scared the Chinese Communists into developing their own nuclear program; they successfully tested their own H-bomb by 1967.

Based on Kefauver’s actions in the Formosa situation, we can hypothesize how he would have reacted to Vietnam. In 1970, Kefauver’s aide Richard Wallace said that “had he been alive… [Kefauver] would have been very doubtful about the escalation in Vietnam. He believed in strengthening the Free World in its heartland. He was an internationalist, but a discriminating one.”

Wallace’s assessment strikes me as correct. Kefauver was concerned about the spreading of Communist influence in Asia, so I think he might have supported America’s initial involvement in the conflict. However, he was clearly opposed to getting involved in a larger conflict – possibly with China, as he had feared in the Formosa crisis – and he would likely have been just as wary of tying America to the future of South Vietnam as he had been to tying us with that of Chiang Kai-Shek’s Chinese Nationalists.

While Kefauver might have voted for the Gulf of Tonkin resolution (which passed 88-2), with reservations, he surely would have opposed Lyndon Johnson’s dramatic escalation of US presence in the conflict. I think there’s a good chance he would have joined Morse’s attempt to repeal the resolution in 1966.

Sadly, we can only speculate; Kefauver’s untimely death deprived us of his unique combination of discernment and courage, which America surely could have used amid the turbulence of the 1960s.

Leave a comment