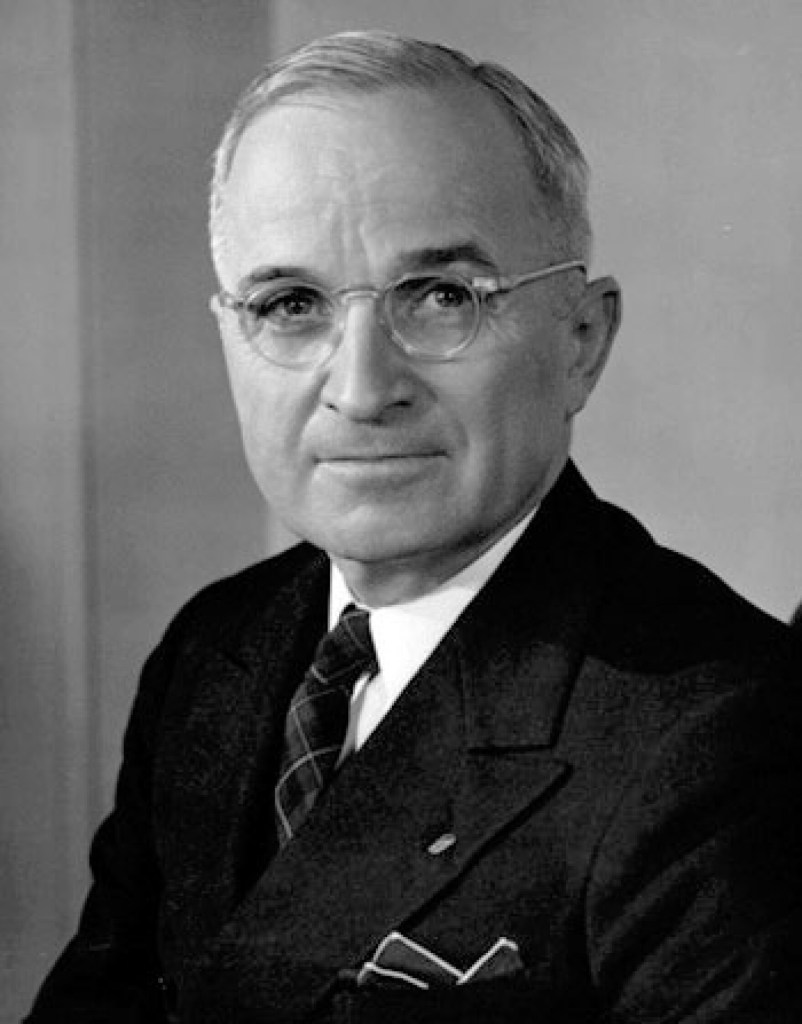

There are multiple reasons why Estes Kefauver didn’t capture the Democratic nomination for President in 1952. But if there was one person most responsible for blocking Kefauver’s path to the nomination, it would be Harry Truman.

Truman, of course, wanted to be the nominee himself. Having stunned the experts with his victory over Thomas Dewey four years earlier, the President felt he deserved a shot at a second full term.

However, the voters weren’t in the mood to give him four more years. His administration was marred by scandal and corruption, the Korean War was grinding toward an unsatisfying stalemate, and Joseph McCarthy was busy whipping up fears of Communists in government. Truman’s public approval rating had plunged to 23% by the beginning of 1952, and it wouldn’t rise above 33% for the rest of his term.

If Truman couldn’t be the nominee, he at least wanted to be able to anoint his successor. The problem was, he didn’t seem to have a choice in mind. Although he ultimately blessed Adlai Stevenson, the eventual nominee, at various times he expressed support for New York Governor Averell Harriman, Chief Justice Fred Vinson, Vice President Alben Barkley, and others.

Truman may have been uncertain about his preferred successor, but there was one person he was clear that he didn’t want. He was implacably opposed to Kefauver from the beginning of the campaign and his opposition never softened, no matter how popular Kefauver was with rank-and-file voters or how many primary wins he racked up.

One of Kefauver’s strongest supporters, syndicated columnist Drew Pearson, found this out the hard way. In the run-up to the Democratic convention, Pearson collaborated with friendly administration staffers to see if the President could be convinced to support Kefauver. They indicated that it was possible.

But at the convention, Pearson was shocked and disappointed to discover that not only would Truman not support Kefauver, he would seemingly do anything in his power to make sure Kefauver wasn’t nominated.

“It has become increasingly evident to me that Truman is bitterly resentful against Kefauver and that [the staffers] were either kidding me or else ignorant of the facts when they thought he was being warmed up,” Pearson wrote in his diary during the convention. “The Truman forces at Chicago are pulling every possible wire to defeat Estes.”

Why was Truman so hostile to Kefauver? They were aligned in many ways. Both grew up in small towns in relatively modest circumstances. Kefauver strongly supported both the New Deal and Truman’s Fair Deal. Both men spoke to the voters in plain, straightforward language. Both were decisive and had the courage of their convictions even when they weren’t popular. Kefauver was even generally supportive of Truman’s moves on civil rights, which the President noticed and appreciated.

The historical record suggests that Truman’s opposition was rooted primarily in matters of personal pique rather than substantive disagreement.

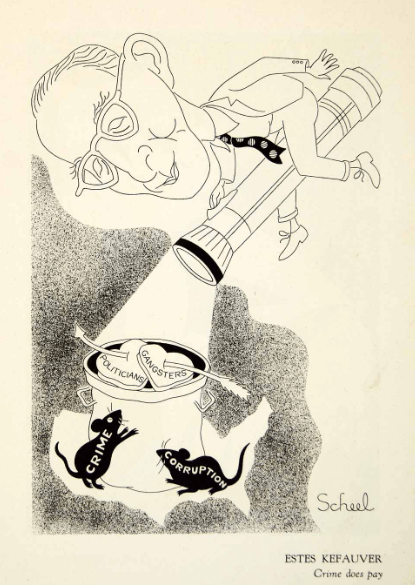

First, Kefauver deeply offended Truman with his conduct of the organized crime hearings. Kefauver’s probe was widely praised as honest and even-handed, unafraid to reveal evidence of criminality and corruption wherever it turned up, even in cities and states run by Democrats.

But for Truman, a dyed-in-the-wool Democratic partisan, that impartiality was exactly the problem. He was furious that Kefauver didn’t focus on Republican corruption in places like Philadelphia and Colonel McCormick’s machine in Chicago.

Truman’s private notes dripped with vitriol in condemning both the investigation and Kefauver himself, whom Truman called “ignorant of history, an amateur in politics, and intellectually dishonest” in one such note from December 1952. Truman believed that Kefauver ran the hearings primarily to boost his own profile and cash in on books and speeches, while throwing his party under the bus.

Truman’s anger was also personal. He was a proud product of the Tom Pendergast machine in Kansas City, one of the stops in Kefauver’s nationwide tour. The hearings – and Kefauver’s subsequent book on them – revealed deep ties between politics, law enforcement, and organized crime in the city. Though Truman was not personally implicated, Pendergast was. I’m sure Truman also did not appreciate Kefauver describing Kansas City as “struggling out from under the law of the jungle” in his book “Crime in America.”

With Truman’s administration already plagued by scandal, the depiction of his political hometown as a den of corruption and iniquity certainly didn’t help. (Truman’s private notes complained that Kefauver’s hearings in Kansas City and St. Louis “made it appear the home state of the President was all wrong and rotten,” even though – he claimed, falsely – the committee found no evidence of wrongdoing there.)

The second reason for Truman’s hatred was even more personal: he resented Kefauver for running against him in the 1952 primaries. In the early months of ’52, Truman refused to decide whether he would run for re-election, essentially freezing the field.

Even though Kefauver visited Truman personally to discuss his plans and to ask for Truman’s endorsement (“After all this counterfeit talk and campaign he had the nerve to ask the President to support him for the nomination for President!” Truman fumed privately), Truman still believed he could decide on his own terms and schedule whether he would be a candidate. One reason for his delay was to figure out the likely Republican nominee. If Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio, whom Truman considered easily beatable, was the choice, he wanted to run; if it was Dwight Eisenhower, not so much.

But Kefauver’s upset win in New Hampshire essentially forced Truman out of the race. Although Kefauver was very careful to avoid criticizing the President while campaigning, the distinction was lost on Truman, who considered the challenge a personal affront.

There may have been a third reason for Truman’s opposition. Merle Miller’s book “Plain Speaking” drew from a series of interviews he did in the early 1960s for a biographical Truman TV miniseries that never materialized. It captures Truman’s reflections in his own words.

During one interview, Miller asked Truman whether he was ever “tortured by ambition” to become President. Truman replied emphatically: “No, no, no. Those are the fellas that cause all the trouble. I wanted to make a living for my family and to do my job the best I could do it, and that’s all there is to it.”

In a later interview, Truman discussed the “weak presidents” he blamed for America falling into civil war. The first of these was William Henry Harrison; Truman pointed out that Harrison’s 1840 campaign greatly inflated his war record and exaggerated the humbleness of his origins. Harrison’s camp falsely claimed that he was born in a log cabin; in fact, his father was a wealthy planter who had signed the Declaration of Independence and served as Governor of Virginia, and he’d been born on his family’s plantation.

Truman then added, “It reminds me a little… and I wouldn’t want this to get out… I wouldn’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings, but it reminds me of that fella from Tennessee that was aching to be President and went around getting his picture taken in a coonskin cap.” He was referring, of course, to Kefauver.

Kefauver didn’t wear a coonskin cap to pretend that he was a frontiersman. But it’s striking that years later, the thing that stuck with Truman was Kefauver’s burning ambition to be President, a quality that Truman distrusted.

Regardless of the reasons, I think Truman’s opposition to Kefauver was a mistake. Not only was Kefauver perhaps the only Democrat popular enough to have a shot at beating Eisenhower in 1952, but he would have continued many of Truman’s policies in office.

By contrast, Stevenson was a poor choice to continue Truman’s legacy. He was a wealthy patrician, the sort of “high hat” that Truman generally distrusted and disliked. Stevenson was considerably less liberal than Truman, and was certainly no Democratic partisan.

And while he lacked Kefauver’s deep ambition for higher office, he arguably went too far in the other direction. His extreme reluctance to be a Presidential candidate ultimately exhausted Truman, who wound up supporting Barkley before the convention, returning to Stevenson only after it was clear Barkley couldn’t be nominated.

Speaking to Miller in the 1960s, Truman was still unimpressed by Stevenson’s elitism and indecisiveness. He said Stevenson “could never understand… how you have to get along with people and be equal with them. That fellow was too busy making up his mind whether he had to go to the bathroom or not.”

Given their obvious differences, why would Truman have ever been interested in Stevenson? He was probably swayed by Jake Arvey, the Cook County machine man who got Stevenson into politics. Truman understood machine politicians, and if Arvey saw something in the guy, that was good enough for him.

But if Truman had been able to swallow his own personal hostility, he might have seen Kefauver as a more natural successor. For a man whose straightforward honesty and courage made him an admired figure after he left office, this was one time Truman’s instincts failed him.

Leave a comment