Being a national political candidate in the 1950s was a novel experience for a variety of reasons. You had to figure out the new medium of television, and work with Madison Avenue ad agencies who would try to market you like a bar of soap or a new breakfast cereal. And jet travel allowed you to fly around the country to make your case, but it could be a double-edged sword. Often, you were flying into little towns and airports that weren’t really designed for jets, which could lead to some amusing – or harrowing, depending on your perspective – encounters.

I’ve previously shared one such incident from Kefauver’s 1956 campaign, when an unscheduled stop at a tiny airport in Wyoming created an unexpected challenge in getting the candidate and campaign staff off and back on the plane. This is a different story from that ’56 campaign, but it falls in a somewhat similar vein.

This story is courtesy of Bill Sturdevant, who served as a press assistant for Kefauver in 1956, as he had for Democratic VP nominee John Sparkman four years earlier. His role with Kefauver meant that he flew around the country with the candidate aboard the “Kefauver Mainstreeter” campaign plane. He shared some anecdotes from his experience with that campaign in a 1979 article in the Washington Post.

Sturdevant’s story dates from the week before the 1956 election. At this point in the campaign, the twin shocks of the Hungarian uprising and the Suez crisis had produced a rally-around-the-flag effect for Eisenhower, cutting off whatever slim hopes the Stevenson/Kefauver ticket harbored for victory. It was clear the Ike was not only going to win, but by a substantial margin.

“[A]ll of us on the Kefauver staff sniffed defeat,” Sturdevant wrote, “and we were grabbing at straws.” Sturtevant wrote that the candidate also understood that defeat was looming.

The morale among the campaign staff was flagging, and they were desperate for any sign of hope, no matter how small.

As the Mainstreeter was preparing to land at a small-town airport in Wisconsin, they received what Sturdevant called “a tremendous and unexpected morale-booster.” They looked out the window and saw an enormous crowd, almost engulfing the airport.

An excited Sturdevant popped down in the seat next to Kefauver. “My God, Estes,” Sturdevant told him, “look at that crowd. Maybe the whole thing’s turned around in the last few days. Why would all these people be out there if they thought we were defeated?”

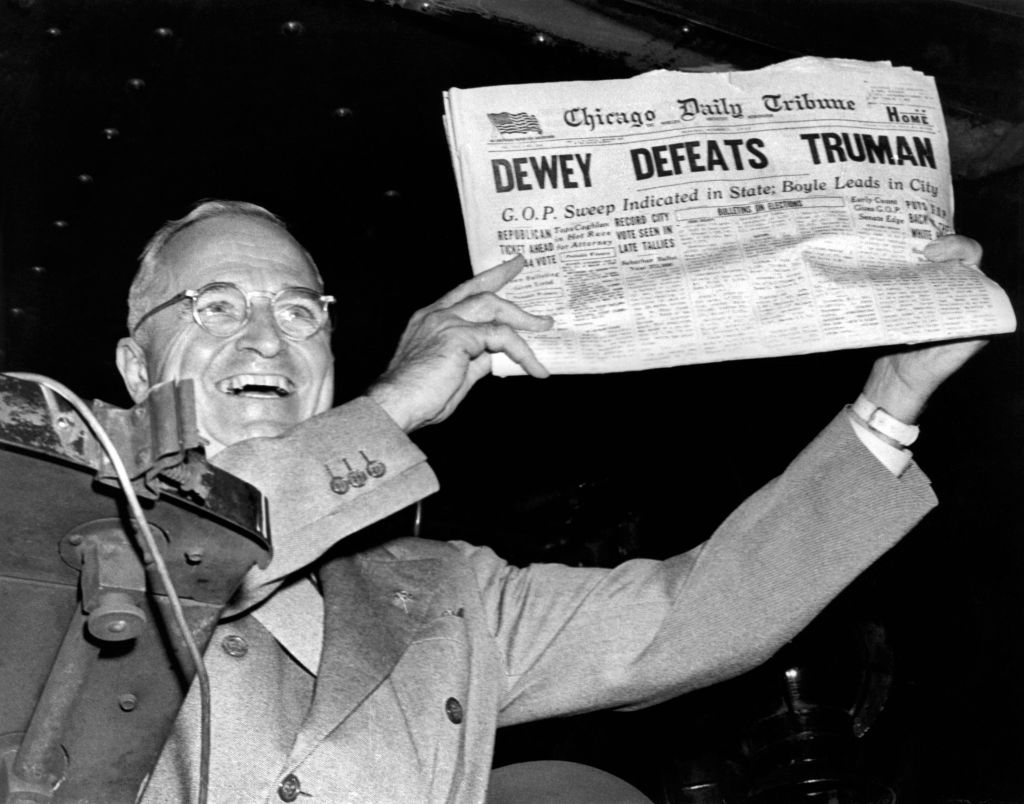

Sturdevant reported that Kefauver broke into his trademark huge grin as “[v]isions of victory danced in his eyes.” Perhaps the election was going to be a replay of 1948, when Harry Truman scored a victory that few people thought was possible.

As soon as they touched down, Sturdevant bolted out of the plane and found the campaign’s advance man. “Great work, Dave!” he exclaimed as he pumped the advance man’s hand. “What a fine job you’ve done.”

“About this crowd, Bill-“ the advance man said.

“I know,” Sturdevant said. “It’s a hell of a turnout. Thanks so much.” He tried to break away, but the advance man gripped his hand tight.

“Bill, listen to me,” the advance man said. “The reason for this crowd-“

“Yes?”

“The reason for this crowd is that this is the first time a four-engined plane ever tried to land here and they’re all out to see the crash,” the advance man concluded.

Like the Wyoming airport from my last anecdote, the airport in Wisconsin was not designed for jets, and the runway was quite short. The landing and takeoff must have been a harrowing experience, especially with a crowd that (although unknown to the folks on the plane) was looking out for a disaster.

Sturdevant said that he never told Kefauver the real reason the crowd was there. And of course, there was no Truman-style upset in the offing. Eisenhower cruised to victory. In Wisconsin, he absolutely crushed Stevenson, winning over 61.5% of the vote. Stevenson won just two counties in the Badger State.

Sturdevant said that the lesson that he would offer to a candidate from this story was “whenever he flies into a strange and crowded airport, he’d be wise to ask the pilot if he’s ever been there before.”

To me, the lesson of the story is what a perilous proposition jet travel could be in that era, especially when small-town airports were involved. Clara Shirpser, the Kefauver staffer who related the Wyoming story, mentioned that the press routinely applauded every time the Kefauver Mainstreeter landed or took off successfully. While this was likely an example of the press corps’ dark humor, it also shows that they understood at some level that these maneuvers were anything but routine in those days.

In the decades to come, jet travel would become routine, and candidate were able to go to and from small towns without incident. But in those days, flying across the country was yet another new frontier for political campaigning.

Leave a comment