Recently, I was watching an old British Pathe newsreel of the opening of the 1952 Democratic convention. It’s on YouTube and it’s short, so I’ve embedded it here:

I liked the fact that Kefauver was the first candidate mentioned, and enjoying the shot of the donkey wearing a coonskin cap. I then watched the segment about Averell Harriman, described as “better known” than Kefauver (highly debatable, though possibly true in Britain, since Harriman briefly served as Truman’s ambassador to the UK).

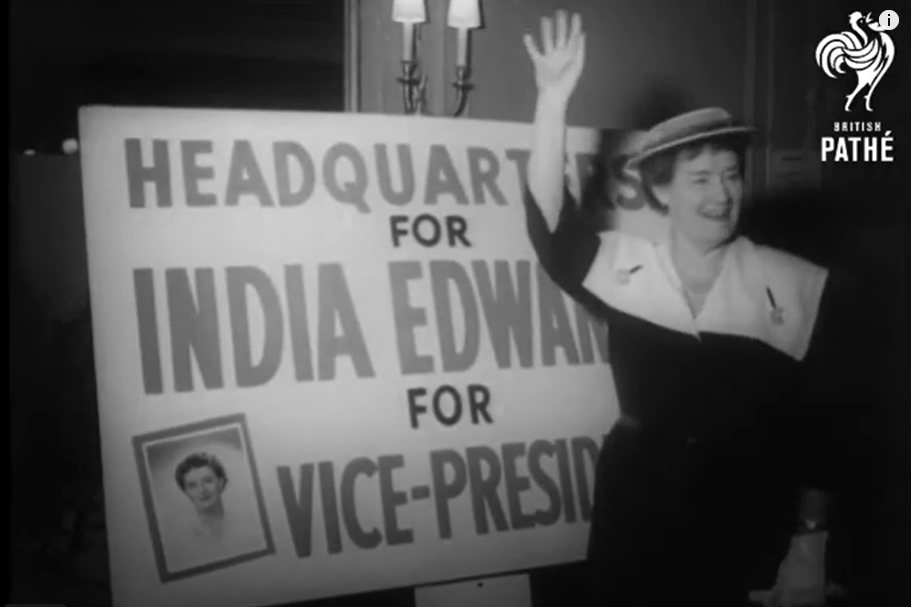

Then came a segment that stopped me cold. “Aiming to be the first lady is India Edwards, Democratic vice chairman.” And there was a cheerful-looking older woman, waving in front of a sign for her “headquarters.” (It’s at the 35-second mark of the video.)

I was stunned, since I had literally never heard of India Edwards before watching this newsreel. Who was she? Was her vice-presidential bid for real? Was it a publicity stunt?

So I did some research. I discovered that the answer to “Was it a real Vice Presidential bid?” was “Sort of” (more on that in a minute. But I discovered that Edwards was very real, and that she had a remarkable career in Democratic politics. It’s a real shame that she, like so many colorful and important characters from the mid-20th century, has largely been forgotten by history. I’m doing my best to correct that here.

India Edwards was born in Chicago in 1895. (“India” was her real first name; it was a family name on her mother’s side.) Her first career was in journalism; after coming up as a reporter, she was the editor of the society and women’s pages for the Chicago Tribune for almost a quarter century. She enjoyed the newspaper business a great deal.

Her personal life was a bit rockier. Her first husband died in World War I. She married again, to an investment banker named John Moffett. They had two children (a son named John, and a daughter named – yep – India) before divorcing in 1937. Her son died in World War II.

In 1942, she married her third husband, Herbert Edwards. He worked for the State Department, so she quit the Tribune and moved to Washington to settle down for life as a housewife, or so she thought.

But then she listened to a speech that Claire Boothe Luce (wife of Time publisher Henry Luce) made at the 1944 Republican convention. As Edwards recounted, “Mrs. Luce attempted to speak for ‘G.I. Jim.’ The implication was that if the boys who had been killed in the Second World War could come back they would say to vote against Roosevelt.”

Well, that really pissed Edwards off. “I thought this was the lowest thing I ever heard of any politician doing,” she said. “She couldn’t speak for my son.”

The very next day, she went down to the local Democratic headquarters and signed up to volunteer. (She had long been interested in politics, but as a staunch Democrat working for the Tribune – whose owner, Colonel Robert McCormick, was an active Republican – she felt it best to steer clear.)

She paid her own way to the 1944 Democratic convention in Chicago (where she got in, ironically, by sitting in the box of Colonel McCormick, her old boss). And she began working hard for the Democratic Women’s Division, writing speeches and press releases.

During the 1944 campaign, she got to know Harry Truman, FDR’s new running mate. He quickly became impressed by her intelligence and work ethic, and he didn’t forget her after he succeeded Roosevelt in the White House.

Edwards had a moment in the spotlight at the 1948 Democratic convention, giving an attention-grabbing speech. To dramatize the high prices prevailing at the time, she brought a bag of groceries and held them up one at a time, stating how much the price of each one had gone up. It made for a dramatic visual, although a bit of a messy one, as one of the items was a steak, which fared poorly in the un-airconditioned amphitheater. She described “holding up the piece of steak and the blood ran down my arm. The photographers kept yelling ‘Hold it up again, India! Hold it up again!’ It was dreadful.”

As head of the Democratic National Committee’s Woman’s Division, she rode with Truman on his famous barnstorming train trip around the country. Unless the reporters accompanying Truman on the tour – and even most Democratic leaders – she was confident throughout the campaign that he would win, an impression that only strengthened when she saw the huge and enthusiastic crowds at each stop. She told reporters, “If you’d see the reaction of the people, you’d know they are going to vote this man into office.”

Truman was moved by her support. At breakfast on the train one day, he told her, “You know, India, sometimes I think there are only two people in the United States who really think I’m going to be elected President. And they’re both sitting at this table.”

To the shock of politicians and reporters – but not Edwards – Truman did win in 1948. And when he won, he told Edwards she could name her place in his administration. She chose to remain on the DNC instead.

She used her influence with Truman to encourage him to appoint women to positions in his administration. But she was strategic about it. She would watch out for openings (“I was a regular ghoul,” she said. “I used to watch the death notices”). And when one came up, she would recommend a specific woman with the qualifications for the position.

And on many occasions, Truman listened. He appointed Georgia Neese Clark as US Treasurer, Freeda Hennock to the FCC, Perle Mesta as Ambassador to Luxembourg, and others, all on Edwards’ recommendation. And then she’d work to smooth any hurdles, sounding out recalcitrant Senators who might refuse to confirm.

At one point, she even persuaded Truman to nominate a woman, Florence Allen, to the Supreme Court. Truman was willing, but Chief Justice Fred Vinson vetoed the idea.

She continued rising through the ranks at the DNC, eventually becoming Executive Director and then Vice Chairman in 1950. Truman even wanted to make her Chairman in 1951, but she declined, feeling the backlash from some men might split the party in the run-up to the election.

That set the stage for the 1952 convention. So, was Edwards actually nominated for Vice President? Well… sort of. Her name was placed into nomination for the position, but it seems to have been more of a ceremonial thing. Edwards herself considered it a “courtesy gesture,” and quickly withdrew from consideration before the vote took place.

She campaigned for Adlai Stevenson vigorously, even though he told her, “India, I don’t know why you would want to support me, because you’re a true liberal, and I’m not.”

She resigned her position with the DNC to work on Harriman’s Presidential campaign. In 1964, she joined LBJ’s position as a consultant to the Department of Labor. He regarded her as a valued advisor; many of his White House papers contained the words “check this with India Edwards.”

In 1977, after finally stepping away from politics, she wrote a memoir titled “Pulling No Punches.” (The title came from Truman; when she’d talked to him about writing a book decades earlier, he advised, “Tell the truth and pull no punches.”)

In that book, she expressed the hope that Rep. Barbara Jordan would become the first female president. “I would gladly work for her,” she wrote.

As you would imagine, Edwards was a tough woman; she had to be to survive and thrive in midcentury politics, which was very much a man’s world. She prided herself on not crying in public, and she dealt with her male colleagues “man to man,” as she said.

She didn’t pull her punches on the job, either. She was a stalwart supporter of civil rights, and wasn’t shy about it. At a party dinner, she was seated across from a racist committeeman from Mississippi, who invited her to a Jefferson-Jackson dinner he was hosting. She replied, “I wouldn’t come and speak to you if you offered me ten million dollars, and you know very well that you don’t want me either. I can’t even bear to talk to you this much. So let’s consider this conversation at an end.”

She also wasn’t afraid to criticize even revered party leaders. During a 1975 oral history interview, she criticized John F. Kennedy for his unwillingness to appoint women to positions in his administration. “Kennedy… never thought of a woman as anything but a sex object,” she said.

India Edwards died in 1990 at age 94. She should be an icon in the Democratic Party, but she’s largely forgotten. Even as Democrats have nominated woman for President in 2016 and 2024 and Vice President in 2020, Edwards’ name is rarely invoked.

I hope this post can do a bit to help rescue the memory of this vibrant, brave, hard-working woman.

Leave a comment