Estes Kefauver spent most of his adult life in the legislative branch of government, first in the House of Representatives and then the Senate. As readers of this site are well aware, he eagerly sought a spot in the executive branch, running unsuccessfully for President twice and as Adlai Stevenson’s Vice-Presidential running mate in 1956.

Late in his life, Kefauver may have had a shot at the judicial branch as well, with President Kennedy reportedly considering him for a seat on the Supreme Court. Possibly. Let’s review the story.

Fade to Black?

In June of 1961, James Free of the Birmingham News reported a rumor that got official Washington buzzing. He wrote that Justice Hugo Black, an Alabama native who’d been appointed to the Court by FDR and was then 75 years old, was ready to announce his retirement. And he added that Black’s seat was expected to be filled by Kefauver.

The capital is a hotbed for political gossip, so it would be easy to dismiss this as idle chatter. But Free was known to be friends with both Black and Kefauver, and through his reporting on civil rights he became close to Attorney General Robert Kennedy as well. If anyone would be able to confirm this story, Free would be the guy.

The proposed swap made sense for other reasons. Black was the dean of the Court’s liberals at that time. His was considered one of the “Southern seats” on the Court; both parties at the time agreed that when Black’s seat came open, it should be filled by a fellow Southerner. (The two men rumored to be at the top of JFK’s Supreme Court short list – Labor Secretary Arthur Goldberg and HEW Secretary Abe Ribicoff – hailed from the North.)

And despite having been a member of the Klan in his youth, Black was a strong supporter of civil rights for black Americans. He would want his seat to be filled by someone who felt similarly. Kefauver was one of the few nationally prominent Southerners who shared Black’s outlook on the issue.

Syndicated columnist Doris Fleeson suggested it was “possible that Black chose this means of hinting to President Kennedy what he deems a desirable maneuver. During his brisk Senate tenure, the liberal Justice was a bold and adroit politician.”

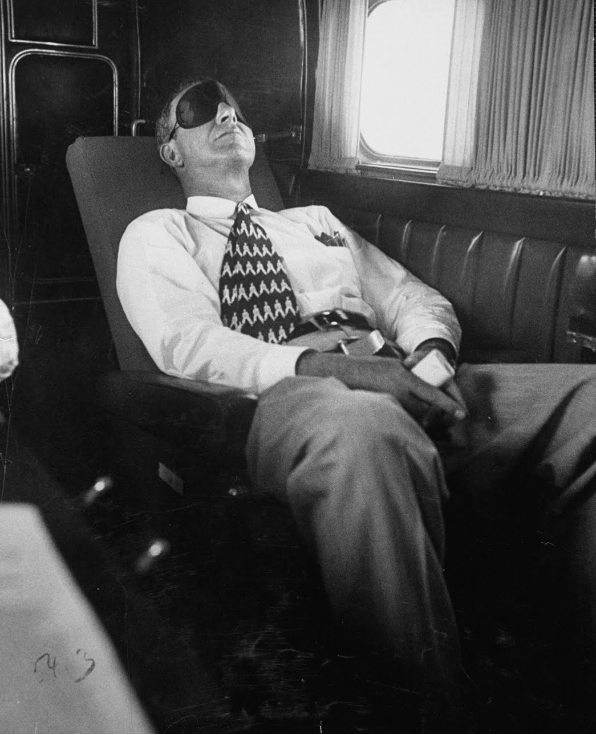

As for Kefauver’s part in this, Free reported that the Senator “has told friends that he is weary of the political ‘rat race.’” Having just survived a difficult primary in 1960, Kefauver knew that the political winds of Tennessee were shifting against his brand of liberalism. And having given up his dream of reaching the White House – and knowing that he would never be considered enough of an insider to join Senate leadership – a lifetime appointment to the Court might have been an appealing prospect.

Kefauver had never served as a judge before, which would make him an unlikely candidate for a Supreme Court seat today. However, this was more common in that era; even Chief Justice Earl Warren had not had any judicial experience before joining the Court.

Naturally, everyone denied the rumor. Black noted that he had already named his clerks for the fall term, and added that he was still vigorous enough to play tennis on a daily basis. JFK’s press secretary Pierre Salinger stated, “If Justice Black intends to resign, he has not informed us of his intentions yet.”

Kefauver called it a “wild pipe dream” and added, “I have no ambition to go on to the Court. I plan to stay in Senate as long as I can.” Asked if he would accept the Court seat if offered, he replied, “That would be a very agonizing decision to make and one I wouldn’t even want to think about when the matter is so nebulous.”

Of course, all these statements fell into the category of “non-denial denials,” which only fanned the flames.

The Plot Thickens

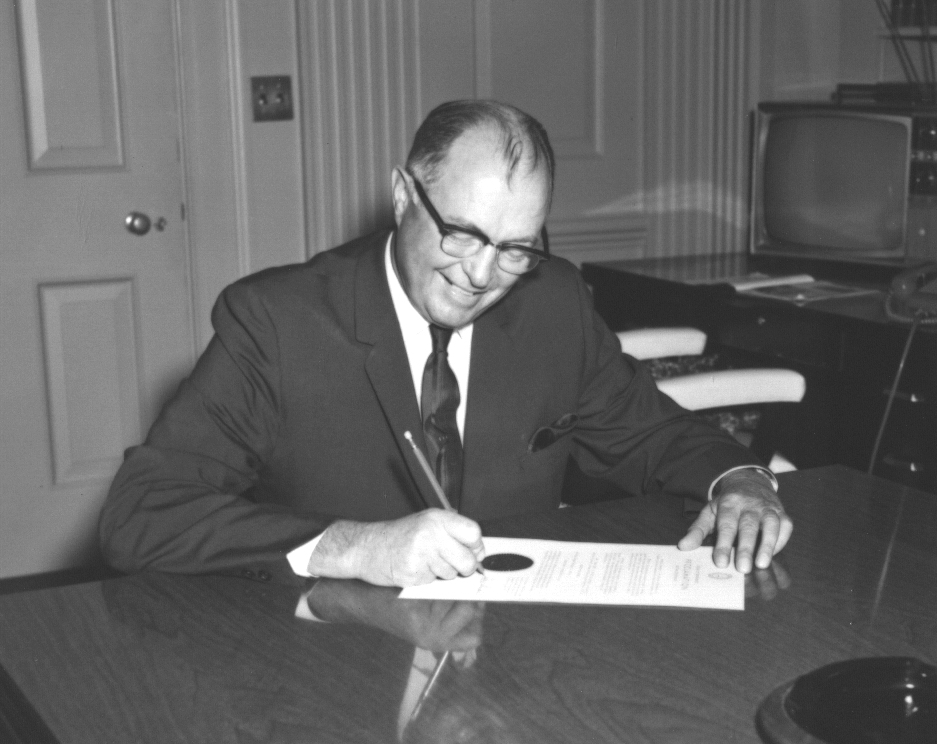

The week after Free ran his piece, the Chattanooga Times reported that it had “learned from a source unusually close to Justice Black that he has definitely decided to retire. That same source was almost as certain that the senior senator from Tennessee is in line to be named the new justice.” The Times added a new wrinkle: Tennessee Governor Buford Ellington would resign his job so he could be appointed to Kefauver’s Senate seat.

Again, there was a certain logic here. Governors in Tennessee were barred from serving consecutive terms. Ellington’s term would be up at the beginning of 1963, and he was not independently wealthy; he would need a job. He was also known to be friendly with Vice President Lyndon Johnson, and LBJ would probably prefer to work with Ellington in the Senate than the stubbornly independent Kefauver.

The rumors reached a fever pitch a couple days later when Governor Ellington came to Washington to meet with both Bobby Kennedy and JFK (the latter meeting supposedly arranged by Johnson). Kefauver also met with the Attorney General within an hour of Ellington’s meeting. Later that day, Ellington stopped by Kefauver’s office for a brief chat. UPI breathlessly reported that “at least two of the conversations are said to have revolved around the shift.”

Again, both Kefauver and Ellington swatted away the rumors. Their respective visits to the White House were just “courtesy calls,” they said. (Kefauver at least had an excuse: he was accompanied by Frank Wilson, newly named a federal judge for East Tennessee, and Kefauver was introducing him to RFK.)

Kefauver chose humor to explain away his meeting with the Governor. “I told Buford I had read in the paper that he was coming up here to take over my Senate seat and that I was going to the Supreme Court,” he said, adding that Ellington replied, “Yeah, I read it in the paper too. It was the first I’d heard about it.”

Public Reaction: Hope and Fear

Despite the attempts to downplay the story, the rumored Court swap became a subject of national discussion.

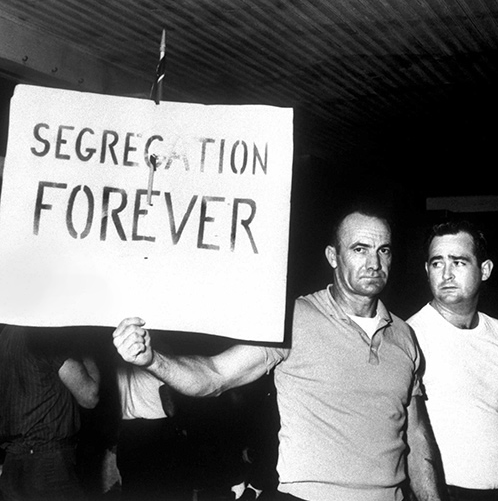

The conservative Alabama Journal was horrified. Their editorial board called Black “a radical Justice of the rankest kind” and condemned the idea of replacing him “with a man like Kefauver, who is as radical as he knows how to be.” They fumed that “the Supreme Court should not be used as a refuge for state trouble makers. Tennessee ought to find some other way to get rid of Kefauver than putting the whole nation at the mercy of another man without the slightest evidence of judicial temperament or experience.”

On the other end of the spectrum, the Baltimore Afro-American expressed its fervent hope that Black would remain on the Court, noting that “for almost a quarter century [Black] has stood unwavering in his dedication to the principle that under the law there must be no first and second-class citizenship.”

They were skeptical that Kefauver would follow in Black’s footsteps, stating that although Kefauver “is stamped from the same liberal mold as Justice Black, we get the impression that he does not view the Constitution in the same flexible concept as Justice Black.” They concluded by wishing Black “continued good health and judicial wisdom.”

And then… nothing. Black did not resign from the Court, and the rumors died down as quickly as they had sprung up. Black remained in his seat for another decade, finally resigning in 1971 after suffering a stroke. He died a week later.

What Went Wrong? Some Theories

So what happened? The historical record is silent. On his deathbed, Black ordered his son to burn his papers, depriving us a chance to know his off-the-record thoughts. As I see it, there are a few possibilities:

- Black changed his mind and decided not to retire. This is a definite possibility. Black was still in good health and mentally sharp; he may have concluded that he still had gas in the tank. Some reporters speculated that he wanted to outlast Felix Frankfurter, who had become the head of the Court’s conservative bloc. However, Frankfurter retired in 1962, and Black remained on the Court for another nine years, so it seems unlikely that this was the reason.

- Kefauver decided that he did not want to join the Court. This is also a possibility. While Kefauver’s path to Senate leadership was blocked, he was chair of the Antitrust and Monopoly Subcommittee, working on the issues that he cared about most. He was conducting high-profile investigations into the steel industry, prescription drugs, and more. This is why I take him at his word that accepting a Court seat would be “a very agonizing decision to me.” It’s possible that he concluded that his Senate work was too important to give up, even for a Supreme Court appointment. And if Kefauver declined, Black may have chosen to stay on, knowing that he couldn’t pass the seat to his preferred successor.

- The Kennedy administration refused to nominate Kefauver for the Court. This seems to me the likeliest explanation. Time magazine implied this was the case in their article memorializing Kefauver’s death; they said JFK “didn’t cotton to the Keef’s independent ways.” The Kennedy administration had a lukewarm relationship with Kefauver, and may not have considered him a sufficiently reliable ally on the bench. Alternatively, the administration may have concluded that Kefauver wouldn’t be confirmed. Although the Senate (at the time) had a tradition of confirming their own, several papers mentioned that segregationist Southerners would likely raise a fuss about Kefauver being chosen for the “Southern seat” on the Court, even though he’d be replacing a staunch liberal in Black. It’s possible that Kennedy didn’t want his first Supreme Court nomination to get mired in controversy.

- The rumors were never true, and Black had no plans to retire. Frankly, I don’t believe this. Free was close enough to both Black and Kefauver that he could easily confirm the truth of the rumor with either of them if he heard it somewhere else. And it seems unlikely that he would jeopardize his relationship with either man by making up the rumor out of thin air. Also, there was an awful lot of smoke for there not to have been any flames.

JFK Waits ‘Til Next Year; Kefauver Doesn’t

With Black remaining on the Court, Kennedy would have to wait until April 1962 to have a chance to fill a seat. Justice Charles Evans Whittaker, who had been an Eisenhower appointee, suffered a nervous breakdown, apparently from agonizing over his decision in Baker v. Carr, in which the Court decided the courts could hear challenges to Congressional redistricting based in the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection. He resigned at the end of March.

Kefauver’s name was floated as a potential replacement, but this time he quickly issued a categorical denial: “There is no foundation to the talk about my being offered or considering such an appointment.” (To me, this confirms that there was a discussion about the Black seat the year prior, and either Kefauver had decided he didn’t want to join the Court or he knew that Kennedy wouldn’t pick him.)

President Kennedy wasted no time choosing Deputy Attorney General Byron White as Whittaker’s successor. Like Kefauver, White had no prior experience on the bench. And the administration ruffled some feathers by declining to consult with Congress or the bar associations, as was customary, before announcing their choice. None of this, however, kept White from being confirmed via voice vote. He served on the Court for over 30 years, earning a reputation as a pragmatic centrist.

I believe that, despite his lack of judicial experience, Kefauver would have made a good justice. He had spent a long time thinking about constitutional issues, and he’d already demonstrated that he had the courage to stand alone on principle when necessary.

However, he would have been denied the chance to pass his signature legislative achievement, the Kefauver-Harris Act on prescription drugs. And given that – tragically – he would have had just a couple short years on the Court, I believe he was better off finishing his Senate mission.

Leave a comment