Over the past few weeks, I’ve been reading “The Last Honest Man” by James Risen, which is a biography of Senator Frank Church of Idaho, with a particular focus on the Church Committee, the 1975-76 Senate investigation into abuses committed by America’s intelligence agencies: the CIA, the FBI, and the NSA.

I strongly recommend the book. Risen tells a gripping tale of incidents such as the CIA’s plots to assassinate foreign leaders (including, at times, the assistance of the Mafia), the FBI’s campaign of spying and harassment against Martin Luther King Jr., and more. He also does a capable job of recounting Church’s lengthy political career, presenting the Senator in all his complexity and not turning him into a purely heroic character.

As I read about Church, I couldn’t help but notice that he was, in a lot of ways, similar to Estes Kefauver. This also led me to consider some of the parallels between the Church Committee investigation and Kefauver’s most famous Senate probe, the investigation into organized crime.

Church was a generation younger than Kefauver, although their Senate careers overlapped from 1957 until Kefauver’s death in August 1963. (Kefauver was on his way to Idaho to campaign for Church’s initial election to the Senate when he made that unscheduled stop in Wyoming that forced him and his campaign team to exit the plane via the emergency chute, a story I recounted previously.)

During that time, they often voted together, and they collaborated on a couple major efforts, most notably the failed attempt to build a government-funded dam at Hells Canyon in Idaho. They weren’t especially close, and Kefauver did not consider Church a protégé of his. But the two men’s careers having quite a bit in common.

Both of them were liberal Senators who represented conservative-leaning states that grew more conservative during their terms in office. During each re-election bid, they faced challenges from their right, which they beat back thanks to a combination of strong retail politics, the ability to defend their positions on critical issues where they were at odds with many of their constituents (opposition to the Vietnam War for Church, support of civil rights for Kefauver), and strategically highlighting certain issues that were popular in their states (opposition to gun control in Church’s case, support of the TVA in Kefauver’s).

Both men were highly ambitious, ultimately seeking the Presidency (Kefauver in 1952 and 1956, Church in 1976). Both of them had an eye for grabbing headlines (“The Last Honest Man” begins with Church holding up a poison dart gun used by the CIA to start off his intelligence hearings), which led them both being derided as publicity hounds by their critics.

Both Church and Kefauver were considered loners and outsiders in the Senate club, in spite of their best efforts. Their stubborn independent streaks led to them being considered untrustworthy by senior leadership in their own party.

Lyndon Johnson denied Kefauver’s request for a seat on influential Senate committees because “I have never had the particular feeling that when I called up my first team and the chips were down that Kefauver felt he … ought to be on that team.”

Similarly, as recounted in “The Last Honest Man,” Arkansas Senator J. William Fulbright, who chaired the Foreign Affairs Committee on which Church served, did not trust his Idaho colleague. “You can’t count on Frank Church,” Fulbright told his chief of staff, Carl Marcy. He contrasted church to other Senators, like Albert Gore and Stuart Symington, whom he could count on to vote as he expected they would.

When it came to running their high-profile subcommittees, Kefauver operated his organized crime probe in a similar fashion to the way Church ran his intelligence investigation. Both men took an independent and fearless approach to seeking the truth wherever it led, with political considerations taking a back seat.

For Kefauver, this meant probing into the corruption of big-city political machines despite the hostility of President Truman and Democratic Party leaders. For Church, he closely examined the misdeeds and abuses of the CIA, FBI, and NSA despite strong pushback from the Ford administration and within his own party, especially once his committee’s findings began to implicate John and Robert Kennedy.

Their bold and apolitical approach won both Kefauver and Church respect and esteem from the public but damaged their Presidential chances. Church was additionally hobbled by the fact that he had promised Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield that he would not campaign for President while his investigation was in progress. The Church Committee didn’t wrap up until March 1976, which meant that Church didn’t enter the primary race until it was already underway – well after Georgia Governor Jimmy Carter established himself as the race’s frontrunner.

As similar as Kefauver and Church were, they were obviously not identical. For instance, Church was famous for his oratorical skills, which Kefauver very much was not. One of the key differences between the two was that Church – especially in the latter half of his Senate career – was an opponent of the establishment, wary of American imperialism in particular. Kefauver, by contrast, saw America – and Western democracies generally – as a force for good overseas (as evidenced by his support for Atlantic Union).

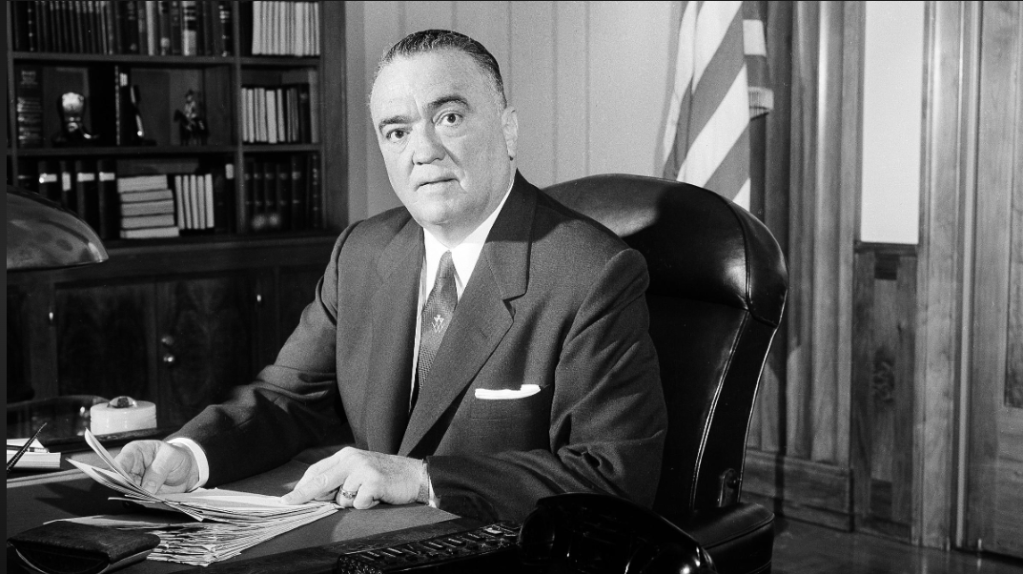

When I read about the Church Committee’s revelations about the FBI’s massive domestic spying program, I couldn’t help but contrast it to the Kefauver’s Committee highly deferential treatment of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, even though there was ample room to criticize the FBI’s distinct lack of zeal in pursuing organized crime.

Risen does point out that Hoover had built up such a network of relationships in Washington, through a combination of strategic information sharing and blackmail, that it would have been virtually impossible to perform a serious investigation of the Bureau until Hoover’s death in 1972.

I wonder how much of the difference in views between Church and Kefauver on foreign policy can be accounted for by the times. In “The Last Honest Man,” Risen states that Church – although he had long been at least somewhat wary of American imperialism – was much more of a conventional Cold War liberal during the early years of his Senate career, before being “radicalized” (Risen’s word) by the Vietnam War, and the lies and deceptions by administrations of both parties as they kept doubling down on a losing effort.

As I mentioned above, Kefauver died in 1963. He did not live to see the Vietnam War, or the assassination of the Kennedys and King, or the Watergate scandal. Would Kefauver have been similarly “radicalized” by these events?

It’s impossible to know for certain, but I think it’s quite possible. Kefauver always retained a healthy respect for dissidents, though he wasn’t one himself. I suspect he would have joined his fellow Senate liberals in turning against the Vietnam War. I think he would have taken the concerns of student protesters seriously.

I also think he would have continued his leftward movement on civil rights, and he was always opposed to violence as a response to racial issues, so he would have been horrified by King’s assassination. He certainly would have been appalled by the shooting of his friend and former colleague JFK, as well as that of RFK. And though he was personally friendly with Richard Nixon, I have no doubt he would have been outraged by Watergate.

I don’t know if Kefauver would have become as anti-establishment as Frank Church if he had lived through the ‘60s and into the ‘70s. But I do think he would have moved in that direction. And I believed he would have supported the Church Committee investigations.

Leave a comment