When you look closely at the particular history of one person or one era, you quickly realize how many stories, even ones that seemed tremendously important in the moment, are lost to the winds of time.

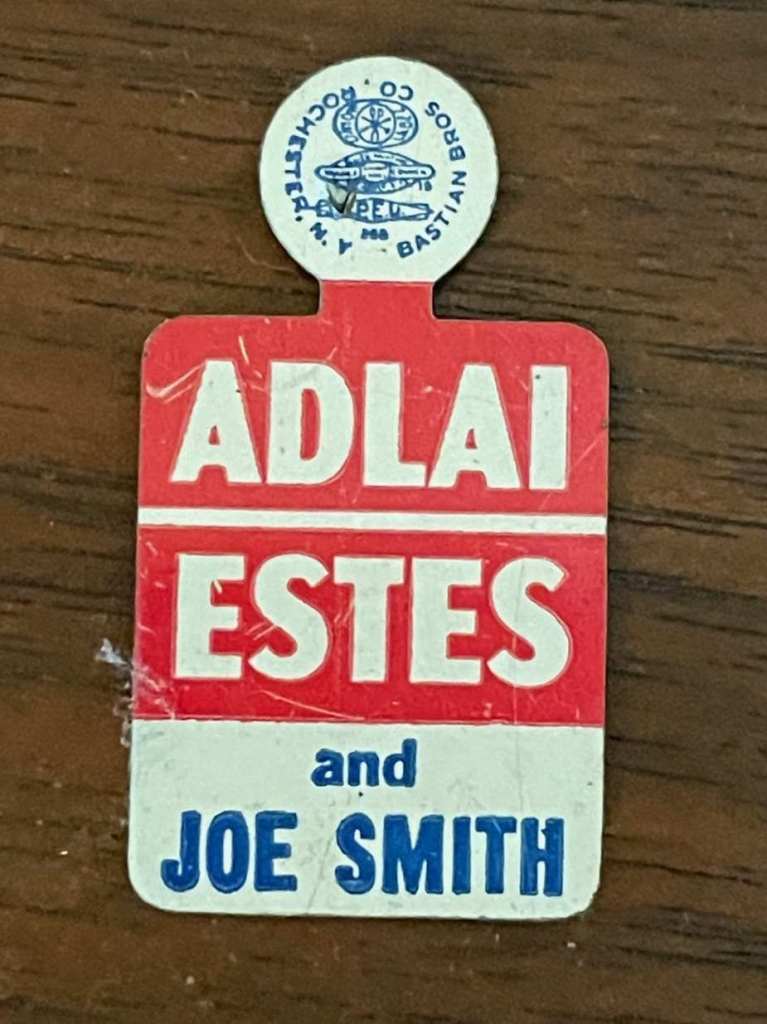

This story was not hugely important, but nonetheless interesting. Here’s a pin from the 1956 Stevenson/Kefauver campaign:

The “ADLAI/ESTES” part of the slogan is straightforward. But who the heck is Joe Smith? My initial assumption was that he was a fictional person, a representation of the common man that the Democratic campaign claimed to represent with slogans like “The ticket for you, not for the few.”

It turns out that I was partially right. Joe Smith was – or at least started out as – a fictional person. But there’s a story to how Joe became part of the campaign.

The story of Joe Smith begins with Terry Carpenter. Carpenter was a businessman from Scottsbluff, Nebraska, who made a fortune with a chain of gas stations and expanded his empire to a variety of other businesses.

Politically, Carpenter was a gadfly. He served a single term in Congress as a Democrat in the early 1930s, but passed on re-election, choosing instead to run for Governor, a race he lost. Over the next two decades, he ran four times for the Senate, twice more for Governor, and once for Lieutenant Governor – and lost each time. He bounced back and forth between the Democratic and Republican parties, changing affiliations five times during his life.

He was a remarkably stubborn man. In 1947, he was elected mayor of Scottsbluff. However, his critics frequently accused him of using his office to enrich his businesses; these criticisms became so frequent that he resigned his post after just six months. Undaunted, he bought up an expanse of land just outside of Scottsbluff and started his own community named Terrytown (which still exists today).

Given his combination of stubbornness and capricious political independence, it’s no surprise that he cherished the nickname “Terrible Terry.”

In 1956, Carpenter was identifying as a Republican, and got himself chosen as a delegate to the Republican convention that year. Unlike the other delegates, however, he was not enamored of the Eisenhower/Nixon ticket. He particularly disliked Nixon as Vice President.

Due to this dislike – or possibly just as a bid for attention – Carpenter was determined to nominate someone else for Vice President, and at least force a floor fight.

He planned to nominate Interior Secretary Fred Seaton – a fellow Nebraskan – for the position. Unfortunately for Carpenter, the convention organizers caught wind of his plan, and got Seaton to sign a letter indicating his desire not to be nominated.

With Plan A foiled, Carpenter turned to Plan B. He told reporters that he still planned to nominate someone other than Nixon “unless I drop dead,” but declined to provide the name “because of the mechanics I hope to use to bring a means to an end.”

When it came time for Vice Presidential nominations, Massachusetts put Nixon’s name into nomination. One state delegation after another passed. Finally, Nebraska’s turn came around.

The delegation chair, Hazel Abel, announced that “one Nebraska delegate, without concurrence of any of the others,’ wished to nominate someone. Asked by convention chair Joe Martin who the nominee is, Abel replied wearily, “The name has not been disclosed to me.”

Abel turned to Carpenter, who said, “I nominate Joe Smith.”

“Joe who?” said Martin.

“Joe Smith,” repeated Abel. The assembled delegates burst into laughter and mock cheers as Carpenter grinned.

“Nebraska reserves the right to nominate Joe Smith, whoever he is,” said Martin, who then continued the roll call. At the end, Massachusetts Governor Christian Herter came forward to formally nominate Nixon, came forward. So did Carpenter.

Martin attempted to recognize Herter, so that he could speak on behalf of Nixon. But Carpenter was chatting away with a group of newsmen in front of the rostrum. An irritated Martin barked, “Will you take Joe Smith and get out of here?” Carpenter left, reporters trailing behind him.

Later, Carpenter explained that Joe Smith was “a symbol of an open convention.” When asked to verify Smith’s identity, Carpenter said, “There’s a Joe Smith in western Nebraska,” further claiming that he lived in Terrytown.

The general reaction to Carpenter’s stunt was a mixture of amusement and annoyance.

“Joe Smith is nothing like Kilroy, is that right?” snarked reporter Chet Huntley, who was covering the convention.

Vermont delegate William Hazlett Upson derided Joe Smith as “nothing but a fictional character created by a Democratic millionaire who was trying to get some personal publicity at a Republican Convention.”

To some reporters, however, Carpenter’s stunt symbolized the way that the Republican convention was stage-managed by party bosses to steamroll the Eisenhower/Nixon ticket to re-nomination, whether the delegates wanted it or not.

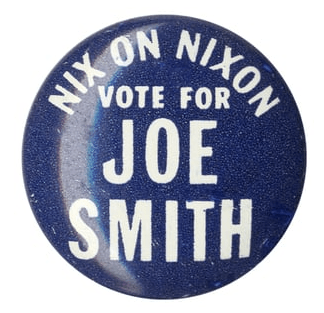

The Stevenson campaign seized on the incident and made it a theme of their messaging. For Democrats, “Joe Smith” was a potent double-pronged symbol: he represented public fears about Nixon, and he symbolized the common man, who could not get so much as a fair hearing from the Republicans.

Nixon was a far more inviting target than the widely popular Eisenhower. Picking on Nixon was also a way for Democrats to make an implicit argument: that Eisenhower, who had suffered a heart attack in the fall of ’55, might not survive the next four years in office. And if he were to die or be disabled, Nixon would become President.

This was a potential avenue to coax moderate voters who liked Ike but were nervous about Nixon into Stevenson’s camp. The campaign definitely did use Joe Smith as an explicit anti-Nixon talking point, as with this button:

More frequently, however, they used “Joe Smith” as a symbol of the common man. It tied neatly into the Democrats’ charge that the Eisenhower administration was run by and for plutocrats and corporate interests.

The fact that the Republican convention refused even to hear about Joe Smith showed their disregard for the will of the people. (The fact that four years earlier, the Democrats had no problem blocking Kefauver – the winner of almost all of their primaries – from the nomination was conveniently ignored.)

In his speeches, Stevenson frequently said, “Let us take the government away from General Motors and give it back to Joe Smith.” He named his campaign plane the “Joe Smith Express,” and even rounded up actual supporters named Joe Smith to show up at campaign events and fly on the plane with him. The Democrats also up a series of “Joe Smith Clubs” across the nation in support of Stevenson.

Kefauver also picked up on this theme. “We have found that the Joe Smiths of this nation have more sense than the Republicans give them credit for,” he said during a rally in Knoxville in late August.

Stevenson largely abandoned the bit by mid-October. Time magazine noted that he had changed the name of his campaign train from the “Joe Smith Special” to the “Stevenson Presidential Special.” And obviously, neither the attacks on Nixon nor the identification with the common man could save the Stevenson/Kefauver ticket from a crushing defeat in November.

As for Carpenter, he actually won – that is, he won election to the Nebraska State Senate. He proceeded to serve there for over 20 years (in between waging additional failed bids for Senate, Governor, and Lieutenant Governor.)

He remained as mercurial as ever – “I can introduce a bill in the morning and be opposed to it in the afternoon,” he said – but he proved to be a reasonably effective legislator. Among the initiatives he got passed were daily television coverage of the state legislature, opening executive committee sessions to the press, collective bargaining for state employees, property tax breaks for low-income seniors, and making the state income tax more progressive.

Carpenter died in 1978 of abdominal cancer at age 78. His obituary ran in the New York Times, and mentioned the ‘Joe Smith” stunt. But his real legacy was his legislative achievements and the town that bears his name. Sadly, outside of Nebraska, Carpenter is as forgotten as Joe Smith, the man he invited to make a point about politics… that’s also been forgotten.

Leave a comment