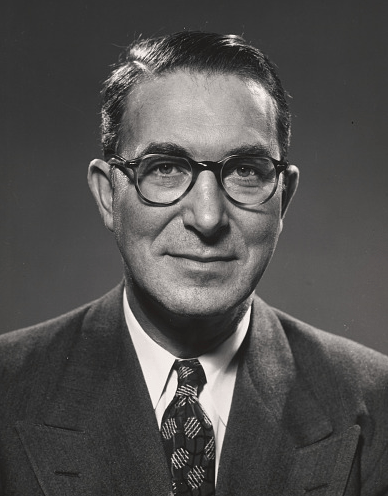

One of the remarkable aspects of Estes Kefauver’s career was his meteoric rise from newly-elected Senator in 1948 to Presidential candidate in 1952. The conventional wisdom is that Kefauver’s televised hearings on organized crime turned him into a national figure, making a run for the Presidency plausible.

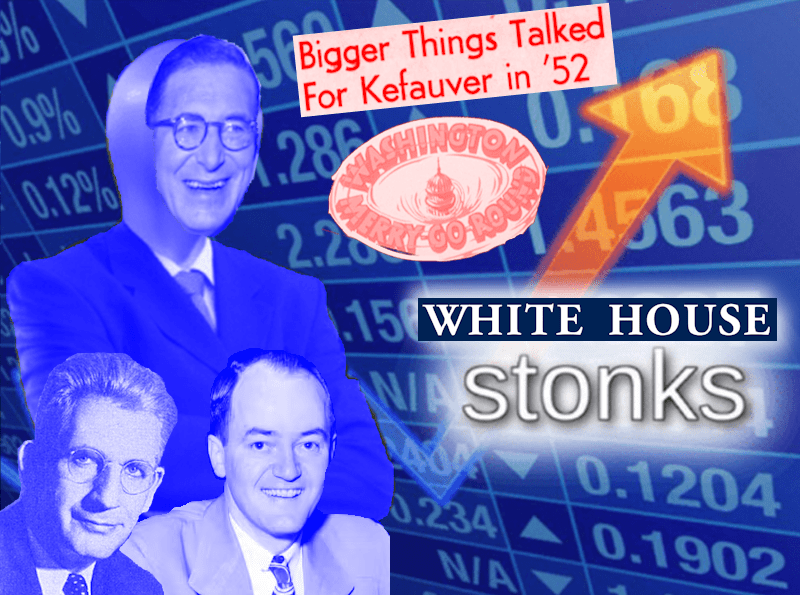

The conventional wisdom, in this case, is largely correct. But it’s also true that Kefauver was already considered a contender for higher office from virtually the moment he arrived in the Senate. Don’t believe me? Consider a column written by J. Lacey Reynolds in the Nashville Tennessean in August 28, 1949, entitled “Bigger Things Talked for Kefauver in ’52.” Kefauver hadn’t even been in the Senate for a full year at this point.

In spite of that, Reynolds writes, “The name of Tennessee’s Sen. Estes Kefauver keeps popping up in talk and print for a place on the 1952 Democratic ticket.” (That place, presumably, being Vice President, since it was assumed at the time that Harry Truman, fresh off his surprise victory over Thomas Dewey, would run again in 1952.)

Fine, you might think, but was this guy just trying to get on Kefauver’s good side with a puff piece? It wouldn’t be the first time a hometown reporter tried that. But Reynolds was quick to dispel that notion: “The talk comes not so much from Tennesseans,” he wrote, “as from a cross section of people and interests throughout the country.”

Why would a newly elected Senator merit such nationwide chatter? Naturally, his surprise victory – triumphing over the Crump-McKellar machine in the process – attracted considerable attention. Reynolds noted that due to his unexpected triumph, “the tall, bespectacled, gregarious Tennessean has acquired a jack-the-giant-killer reputation.”

But Kefauver’s growing reputation wasn’t solely due to his electoral strength. Reynolds quoted Robert S. Allen, who was writing Drew Pearson’s “Washington Merry-Go-Round” column while Pearson was on vacation. Allen mentioned several newly elected Democratic Senators who might be VP material in ’52, including Hubert Humphrey, Illinois’ Paul Douglas… and Estes Kefauver.

Allen praised Kefauver for being “uncompromising in making his campaign promises,” and noted that he alone among freshman Southerners in supporting Truman’s “Fair Deal” programs, “including civil rights.” In conclusion, Allen wrote, Kefauver “stands out among his Southern colleagues like the Washington Monument does in the capital.” This was a statement that would prove true for Kefauver for the rest of his career.

Reynolds echoed Allen’s appraisal, writing, “Although a Southerner, Kefauver’s voting record so far would be widely acceptable in the north and west.” This was becoming an important consideration; after the Dixiecrat debacle in 1948, it was clear that any Southern politician with a record of supporting segregation would no longer have a chance at national office. The Democrats were facing a dilemma that would continue to haunt them for decades: they depended on the “Solid South” as the core of their national base, but could no longer afford to ignore civil rights. In theory, Kefauver – a Southerner who wasn’t retrograde on racial issues – could appeal to the Democratic base everywhere.

But it wasn’t just his support for Truman’s program or his moderation on civil rights that made Kefauver a contender. He was also developing a reputation on his own signature issues. Reynolds wrote that Kefauver’s “fights for public power, small business and world peace have attracted much more attention than normally comes to a senate freshman.” At the time of Reynolds’ piece, Kefauver was getting ready to attend an inter-parliamentary conference in Europe, his first step in attempting to shape the newly formed NATO into his much-desired Atlantic Union,

Reynolds also praised Kefauver for his work ethic both in the Senate and on the campaign trail, his speechmaking ability, his radio and TV appearances (which “brought him considerable attention in the heavile populated Eastern states”), and his touch with people from all walks of life. “He has a way of plowing through a crowd,” Reynolds wrote, “introducing himself, saying a few words and leaving the impression that he really is an old friend.” This gift of personal connection remained central to the Kefauver mythology throughout his life.

Naturally, Kefauver downplayed the national talk. “He says he wants to make the people of Tennessee the best senator possible,” Reynolds wrote.

Later on in the piece, Reynolds shared an item that probably explained a lot about Kenneth McKellar’s antipathy toward his junior colleague. “Senator Kefauver receives at least ten times more press attention than Senator McKellar, despite the latter’s seniority and importance in the senate,” Reynolds wrote. “Much of the mention that is made in newspapers about the senior senator is not complimentary.”

Suddenly, McKellar’s loathing of Kefauver makes considerably more sense.

Leave a comment