Studying a particular period of history really does kind of feel like being able to read a foreign language.

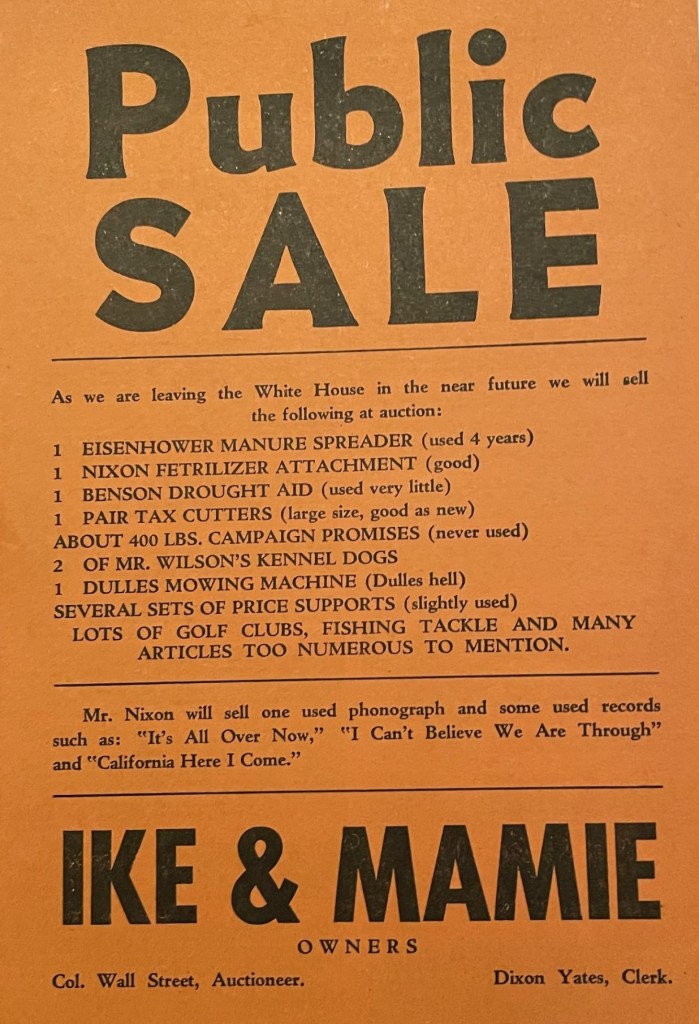

Take, for instance, this political poster from 1956:

Most people with a decent knowledge of American history could tell that this is a joke at the Eisenhower administration’s expense. But most of the jokes on this poster are essentially obscure to a modern audience. On the other hand, because I have studied this period of our history – and this election in particular – quite a bit, I can decipher the whole thing. And because you’re reading this post, soon you’ll be able to understand it too!

So let’s take a trip back to 1956 and see what passed for political humor:

- The poster is advertising an “auction” of the sort typically associated with an estate sale or an eviction. In this case, the Eisenhowers are supposedly anticipating leaving the White House after losing the 1956 election, and are therefore selling off “property” they no longer need.

- I’m sure I don’t need to explain the “Eisenhower Manure Spreader” or the “Nixon Fertilizer Attachment.” Some political attacks are evergreen, shall we say.

- The “Benson Drought Aid” is a reference to Ezra Taft Benson, who served as Eisenhower’s Secretary of Agriculture. Benson was philosophically opposed to providing financial aid to struggling farmers, as he considered this socialism. (Kefauver, who spent a lot of the fall campaign in farm states, frequently attacked Benson in his speeches, usually to wild applause.) In one particularly infamous incident, in June 1953 Benson visited a drought-plagued portion of Texas and suggested that the Governor Allen Shivers ask the people to pray for rain. (Later in life, Benson would serve as President of the Church of Latter Day Saints. Prior to that, in 1968, the John Birch Society tried to nominate him for President on a ticket with Strom Thurmond. As it turned out, George Wallace had the segregationist vote sewn up that year; he considered Benson as his vice president before settling on Dr. Strangelove, Curtis LeMay.)

- The “tax cutters” bit references the fact that Eisenhower promised to cut tax rates during his campaign in 1952, then refused to do so – over the strenuous objection of members of his own party – while in office, arguing that tax cuts were irresponsible until the budget was balanced. Modern-day progressive are fond of pointing out that the top marginal tax rate during Eisenhower’s era was 90 percent, conveniently omitting the fact that this rate only applied to the portion of individual incomes over $400,000 (roughly equivalent to $3.5 million today).

- The line about “campaign promises (never used)” was a common Democratic line of attack on Eisenhower, that he had ignored or gone back on the promises he made when running in 1952. The Stevenson/Kefauver campaign made a whole series of ads based on this theme called “How’s That Again, General?” in which they quoted something Eisenhower had said in ’52 and then had Kefauver explain how the General’s promises hadn’t matched reality. (You can see some of those ads in this post.)

- “Mr. Wilson” was “Engine Charlie” Wilson, the former General Motors CEO who became Eisenhower’s Secretary of Defense. (During his confirmation hearings, Wilson took flak for his reluctance to sell his GM stock before taking the Defense job. Asked if he would be willing to make a decision as Defense Secretary that would hurt GM, he retorted that “for years I thought that what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. This was later twisted into “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country.”) Wilson was fond of folksy expressions; the “kennel dogs” references one that got Wilson in hot water. During a speech in Detroit in October 1954, Wilson explained his opposition to benefits for unemployed workers by saying this: “Personally, I like bird dogs better than kennel dogs. The bird dogs like to get out and hunt for their food, but the kennel dogs just sit on their fannies and yell.” Oddly, unemployed workers didn’t appreciate being called lazy dogs.

- The “Dulles mowing machine” references John Foster Dulles, who was Eisenhower’s Secretary of State. (Dulles Airport outside of Washington, D.C. is named in his honor.) Dulles supported a policy of “massive retaliation,” in which America would vow to respond to any attack with a much bigger counterattack, in order to deter opponents from striking. If you’re thinking this is a strange policy for a country’s chief diplomat, well… that’s where the joke comes from. (The “Dulles hell”/”dull as hell” part at the end is just a dumb pun, as there was nothing dull about his brinksmanship.)

- The “price supports (slightly used)” is another jab at Benson, who was also opposed to price controls on farm products, preferring a system of “flexible price supports.” When he tried to explain this system to a group of farmers in South Dakota, they responded by pelting him with eggs. (You can understand why Kefauver often made Benson the villain of his campaign speeches that year.)

- The line about golf clubs and fishing tackle references Eisenhower’s well-documented love of these pastimes, which prompted criticisms that he spent too much time on the golf course or the fishing hole and not enough time in the Oval Office.

- The joke about Nixon’s phonograph and the song titles are basically self-explanatory, although it’s worth noting that he actually had a fair bit of musical talent.

- The name of the auctioneer, “Col. Wall Street,” references the belief that Eisenhower – who stocked his Cabinet with business magnates – was governing for the benefit of big business rather than the average man. To borrow a line from Hubert Humphrey, “The Republican Party is run by four generals: General Eisenhower, General MacArthur, General Electric, and General Motors.”

- Faithful readers of this site will no doubt get the joke in the clerk being named “Dixon Yates.” If so, good for you; you have been paying attention! If not, here’s the story of that scandal.

The takeaway here is that the stories and scandals that seem so important in the present day are largely washed away by history. When we think of the Eisenhower administration today, we tend to think of it as hugely popular and kind of boring. Figures like Engine Charlie Wilson, John Foster Dulles, and Ezra Taft Benson are mostly forgotten, and stories like Dixon-Yates and the battles over agricultural price supports that grabbed many headlines in their day don’t even rate a footnote in the history books.

When the historians a half-century or more from now are looking back at this era, it’s interesting to imagine what they’ll remember, and what they’ll ignore or forget. It’s worth keeping in mind that most of the things we discuss today – even things that seem important – will ultimately be dust blown away by the winds of history.

Leave a comment