As we saw in previous articles on boxing and baseball, Estes Kefauver didn’t hesitate to use the power of his Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly in the realm of sports. Whether he was proposing a federal commission to get the mob out of boxing or threatening Congressional action in order to force Major League Baseball to add more teams, one may have gotten the impression that Kefauver never saw a federal intervention into sports that he didn’t like. But on at least one occasion, he argued that the government should stay out of a sports-related dispute.

In the late 1950s, football was in a similar spot to baseball: there were a lot of cities thirsty for professional teams, but the existing league (in this case, the National Football League) seemed unwilling to expand in order to meet that demand. As a result, a proposed new league arose to fill the unmet need.

The American Football League was primarily the brainchild of two wealthy Texans, Lamar Hunt and Bud Adams, who wanted to bring pro football to their state. Each man had separately tried to buy one of the NFL’s weakest franchises, the Chicago Cardinals, and move it to Dallas and Houston, respectively. Their offers were rebuffed. So they approached the NFL about expansion, only to be turned away again.

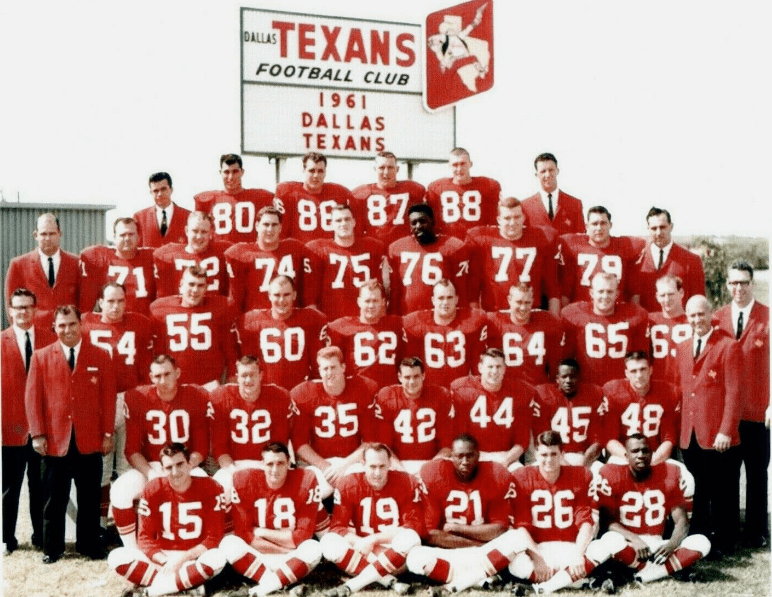

Denied entry into the NFL, they decided to start the AFL as a rival circuit. The Dallas Texans and Houston Oilers were two of the original six charter AFL franchises chosen in August 1959; the other proposed cities were New York, Los Angeles, Denver, and Minneapolis-St. Paul. (Buffalo and Boston were added later.) The AFL chose former South Dakota governor Joe Foss as its commissioner.

No sooner had the AFL announced its plans when, all of a sudden, the NFL decided that expansion might not be such a bad idea after all. (Longtime NFL Commissioner Bert Bell, who had opposed expansion, died in October; it’s said that Chicago Bears owner George Halas was polling other owners to gauge their support of expansion at Bell’s funeral.)

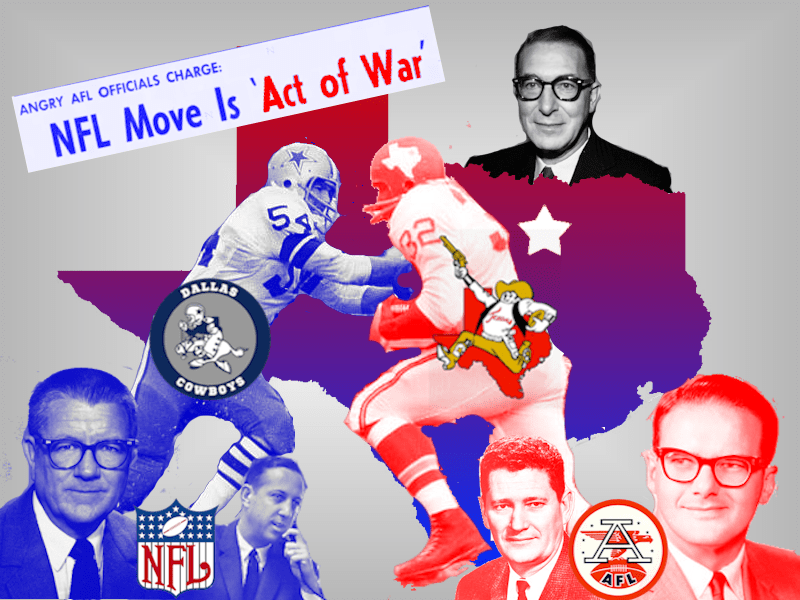

In January 1960, the league voted to expand to Dallas and Minneapolis-St. Paul – which just so happened to be two of the AFL’s planned cities. Max Winter, the planned owner of the AFL’s Minnesota franchise, opted to join the NFL instead. The NFL’s Dallas franchise went to a group headed by Clint Murchison – and prepared to go head-to-head with Hunt and the AFL.

Predictably, the AFL reacted with outrage, proclaiming the NFL’s move an “act of war.” Commissioner Foss vowed that his league wouldn’t take the move lying down. “We are looking into possible courses of action through the courts, Congress, or any other means,” Foss told the UPI. “The AFL definitely will take action.”

With his mention of Congress, Foss likely had Kefauver specifically in mind. Having just seen the Senator go to bat for the Continental League against Major League Baseball, he no doubt hoped that Kefauver would stand up for the AFL against what he perceived as the NFL’s attempt to smother the new league in its crib. (He had reason for this belief; Kefauver had earlier warned the NFL that his subcommittee would be on the lookout any attempt to sabotage the AFL.)

As it turned out, though, Kefauver saw this matter differently. He didn’t believe that the AFL had established squatter’s rights on Dallas just because they’d decided to put a team there first. In his view, neither league had an exclusive claim on the city, and they could fight it out in the marketplace. “I’m for expansion of football,” Kefauver said to the AP, “but it is not a question of rights. It is a question of who has the better product in a city, if he produces it fairly, without monopolization and without pushing anyone around.”

Paul Rand Dixon, chief counsel for the Monopoly Subcommittee, agreed with Kefauver’s view. “They are businesses in commerce,” Dixon said, “Rather than restraint, there is supposed to be competition.” Dixon believed that the Senate’s interest was in fostering the conditions for football to expand, not in legislating territorial rights in specific cities.

Also, as new NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle (elected at the same meeting where the owners voted to expand to Minnesota and Dallas) pointed out, the AFL’s position was a tad hypocritical, since they planned to place franchises in New York and Los Angeles, two cities where NFL franchises already existed. “They moved into our territory in New York and Los Angeles… why shouldn’t we be allowed to move into Dallas?”

In response to Rozelle’s question, Hunt fired back: “It’s not the same at all. In our case it’s just like a little dog going into the big backyard of a big dog. But in their case it’s the big dog going into the little backyard and asking the little bitty dog if there’s not room for him. It’s the size of the backyard that counts.”

Angry AFL owners also pointed to a prior statement by Washington Redskins owner George Preston Marshall, who had long opposed expansion because he feared a new team in the South would cut into the revenues of his radio network. Marshall had claimed that the NFL owners who favored expansion did so specifically to thwart the AFL.

Dixon appeared skeptical of Marshall’s claim (especially since the Washington owner ultimately voted in favor of expansion). “This is something that would have to be proved,” Dixon said. “Was [Marshall] talking through his hat or not? Is this a bona fide expansion or not?”

As it turned out, it was a bona fide expansion. Murchison’s Dallas Cowboys debuted in 1960, with Winter’s Minnesota Vikings taking the field the following year. As for the AFL, Hunt kept the Texans in Dallas, sharing the Cotton Bowl with the Cowboys.

Although the Texans outdrew the Cowboys in 1960 and 1962 and had far more success on the gridiron – even winning the 1962 AFL championship – Hunt saw the writing on the wall and decided to move for ’63. After taking a close look at Atlanta and Miami, he ultimately moved his team north to Missouri, where they became the Kansas City Chiefs.

The AFL, thanks in no small part to their television deal with ABC, proved to be a success. In fact, it was so successful that it wound up merging with the NFL in 1966. Emmanuel Cellar, Kefauver’s longtime ally in anti-monopoly activities, tried to fight the merger. But the House – apparently at the behest of Senator Everett Dirksen – attached the merger approval as a rider on a tax bill, bypassing Cellar’s committee. Kefauver, of course, was no longer around then to stop it. I can’t help but wonder how the history of the sport might have changed if Kefauver had been alive and able to prevent the merger.

Leave a comment