When one thinks of Estes Kefauver and organized crime, the obvious connection is his famous televised hearings that introduced mainstream America to the Mafia and made Kefauver a national celebrity.

The typical narrative of Kefauver’s career is that once he wrapped up that investigation in late 1951, he never returned to the subject again. But the crime hearings weren’t actually Kefauver’s last foray into the issue. He dealt with it indirectly during his juvenile delinquency hearings in the mid-’50s (the subject of a future post).

And he had a more direct confrontation with the mob in 1960, when he investigated the sport of boxing. Kefauver’s hearings revealed the truth about the sport’s unsavory associations – as well as how the athletes at the center of the sport were exploited by the industry that had sprung up around them.

The IBC: Boxing’s Midcentury Monopoly

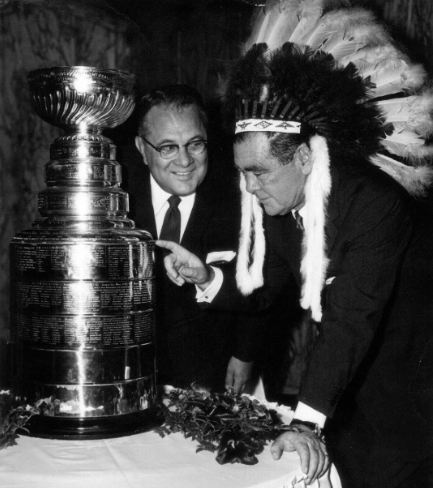

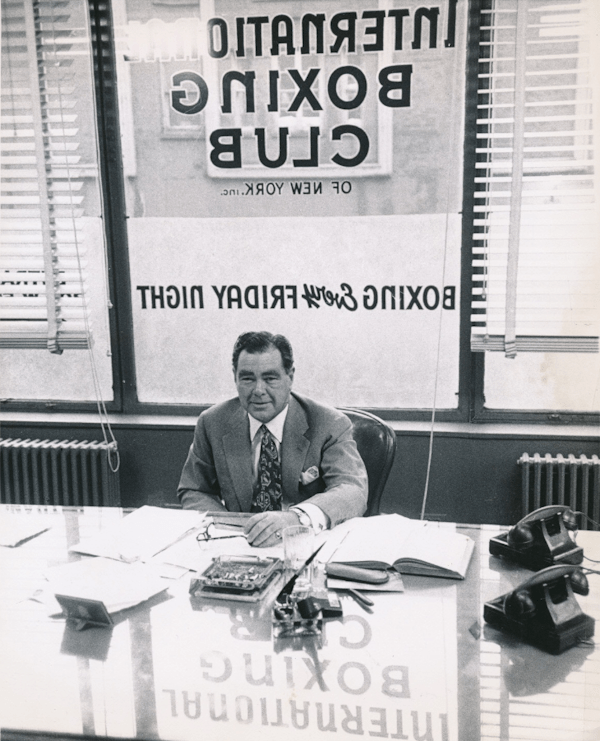

Kefauver’s investigation centered around the International Boxing Club of New York, founded in 1949 by Jim Norris and Arthur Wirtz. (Those names may sound familiar to hockey fans, for good reason. Norris and Wirtz owned the NHL’s Chicago Blackhawks. The Wirtz family still owns the Blackhawks to this day. Norris’ father owned the Detroit Red Wings, and the Norris Trophy – awarded each year to the NHL’s best defenseman – is named in the father’s honor.)

Norris and Wirtz created a central body to promote boxing matches. They owned two arenas – the Detroit Olympia and Chicago Stadium – that were popular fight venues. But the real prize was New York’s Madison Square Garden, where the biggest and most prestigious bouts were held. In the 1940s, fights at MSG and other New York venues were promoted by the Twentieth Century boxing club, run by Mike Jacobs.

But when Jacobs suffered a stroke in 1946, MSG was suddenly in the market for a new promoter. And leading heavyweight contender Joe Louis, who was managed by Jacobs, needed new representation. Seizing the opportunity, the IBC bought both the right to promote fights at MSG from Jacobs for $100,000, and the right to manage four top contending fighters from Louis (who decided to retire) for $160,000.

With that, the IBC had a virtual hammerlock on boxing in America. They controlled the best venues and the best fighters in the sport. Within their first six years, the IBC promoted all but four championship fights in the US. They also had a lucrative contract to broadcast fights on national TV. In short, it was a pretty sweet deal.

Of course, there was another term for the IBC’s control of boxing: a monopoly. Or so said the Department of Justice, observing that the IBC now had controlled the championships in three weight divisions, as well as the biggest venues in the sport. Norris and Wirtz made a weak attempt to evade these charges by spinning off the fighter-management part of their empire into an allegedly separate company, but the DOJ wasn’t fooled.

Seeking a justification, the IBC leaned on the Supreme Court’s 1953 decision in Toolson v. New York Yankees, confirming that Major League Baseball was exempt from antitrust laws. (For more on the Toolson decision, see my article on Kefauver and baseball.) The IBC reasoned: hey, baseball’s a sport, we’re a sport, so shouldn’t we have an antitrust exemption too?

By a 7-2 vote, the Supreme Court shot down the IBC’s reasoning, holding that the antitrust exemption was unique to baseball. (Justice Felix Frankfurter pointed out the ridiculousness of the Court’s logic in a scathing dissent that read in part: “It would baffle the subtlest ingenuity to find a single differentiating factor between other sporting exhibitions, whether boxing or football or tennis, and baseball… It can hardly be that this Court gave a preferred position to baseball because it is the great American sport. I do not suppose that the Court would treat the national anthem differently from other songs if the nature of a song became relevant to adjudication.”)

Having settled the antitrust question, the courts found the IBC an illegal monopoly and forced them to dissolve. The IBC appealed, but the Supreme Court swatted them down again in 1959, and the IBC sold off their operations that year.

Kefauver KOs the Rogues’ Gallery

If the IBC was already dead, why hold hearings? The court cases revealed that the sport of boxing was tied up with some very troubling characters – including some key figures who were reputed to have mob connections. In addition, the cases revealed disturbing stories of under-the-table payoffs and rigged bouts. Meanwhile, the fighters themselves were often underpaid and cheated, and left to die in pain and poverty when their box-office appeal waned.

Kefauver, an avowed boxing fan, was disturbed by what he’d heard and was determined to shine a spotlight on the sport’s dark corners. And so in December 1960, just a couple months after the conclusion of the investigation into baseball, Kefauver’s subcommittee began holding hearings on boxing. As usual, he was assisted by a top-notch staff, led by chief counsel John Bonomi.

Time magazine wrote that the hearings exposed “the octopus grip of the underworld on U.S. boxing.” The subcommittee scrutinized the central role of Frankie Carbo in the IBC. Carbo came up as a gunman for bootleggers during Prohibition; later, he worked with Murder, Inc. and became a soldier in the powerful Lucchese crime family.

Although Carbo had no official role with the IBC, it was known that he participated actively behind the scenes. At the time of Kefauver’s hearings, Carbo was doing time on Rikers Island for managing fighters and making fights without a license. However, the hearings yielded alarming discoveries about the depth of Carbo’s entanglement with the IBC.

Former IBC vice president Truman Gibson (described by Sports Illustrated as having “the sincerity of a used-car dealer”)admitted that virtually all of the IBC’s fights ran through Carbo. Gibson claimed that the IBC decided to “live with Carbo” so that they could “maintain a free flow of fighters without interference.” The price of living with Carbo apparently included the IBC “employing” his wife for 3 years at $45,000 per year. (Gibson acknowledged that “it looked… better on our record, not even considering the possibility of being called before a Senate investigating committee, to have Viola Masters down instead of Frank Carbo.”)

The payout to Carbo’s wife came on top of the secret cuts that he received as an unacknowledged manager and/or promoter of the fights put on by the IBC. Gibson listed so many figures in the boxing world connected to Carbo that Bonomi summed it up by saying, “Almost every leading manager or promoter in the U.S. is either closely associated with or controlled by Frankie Carbo in some degree.”

Gibson wasn’t the only one to describe Carbo’s grip on the boxing world. Manager Hymie Wallman testified about a title fight involving Orlando Zulueta, whom he managed. Carbo, although not publicly connected to the fight, demanded $5,000 to allow it to take place. On the eve of the bout, Carbo contacted Wallman to tell him that if Zulueta won, Lous Viscusi, the other boxer’s manager, would get “a piece of the fighter.”

Nor was Carbo the only prominent boxing figure with mob ties. His lieutenant Blinky Palermo, another under-the-table manager, had received thousands in payments from the IBC, in addition to secret payments for fighters that he managed.

Gabriel Genovese (nephew of Don Vito Genovese) served as Carbo’s bagman, accepting payments to facilitate fights. St. Louis gangster John Vitale had a controlling interest in then-leading heavyweight contender Sonny Liston.

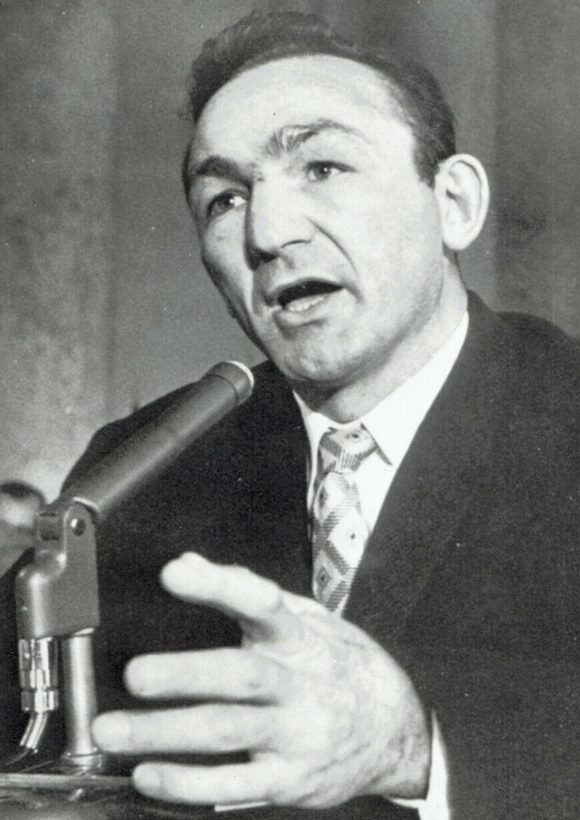

Perhaps the dramatic highlight of the hearings occurred when the subcommittee interrogated Norris, the former IBC president. In 1955, Norris avoided prosecution by telling the New York State Athletic Commission that he never discussed fights or fighters with Carbo. To the subcommittee, however, Norris conceded that this statement “isn’t 100% true… I have to admit that.” (Kefauver’s arch reply: “It sounds to me like it is 100% untrue.”)

Although he characterized his relationship with Carbo as “a reluctant one,” Norris admitted that he “mentioned to Frank Carbo that possibly he might have some suggestions as to how some of these problems [in boxing] might be eased for my organization.” Norris admitted that Carbo served as the “convincer” to get leading boxers to fight in IBC matches.

The Fighters Step Into the Ring

The most compelling testimony came from the fighters themselves. Former middleweight champion Jake LaMotta admitted taking a dive in a 1947 fight, saying that he’d been made to do so in order to get a shot at the title. (LaMotta’s disclosure led to him being excommunicated from the boxing world until the movie “Raging Bull” revived his reputation two decades later.)

Ex-lightweight champion Ike Williams testified that he’d won over $1 million during his fighting career, but that he had been defrauded of most of the money by his manager Palermo and now relied on welfare to make ends meet. (He also testified that he had been offered money to throw fights on several occasions, though he said he always declined.)

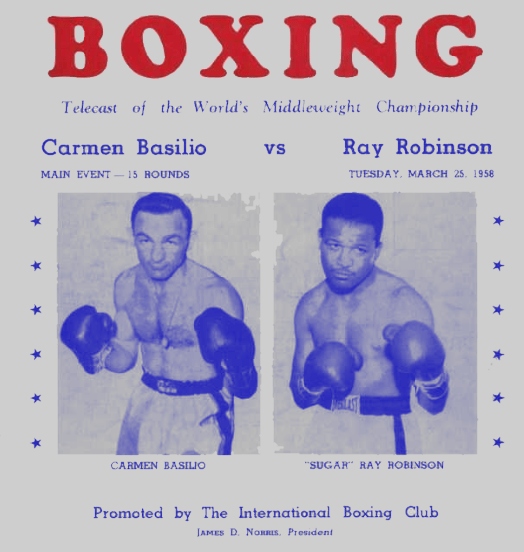

Arguably, the hero of the hearings was Carmen Basilio. The son of onion-farming Italian immigrants, Basilio grew up in upstate New York. Despite being just 5’6½”, Basilio was a ferocious fighter who eventually rose to claim the world welterweight and middleweight titles by the mid-‘50s. Basilio was in the late stages of his career by the time of the hearings, but he was still hanging on. And so it came as something of a surprise that he was willing to take a stand and clearly denounce the filth he saw in the sport.

Basilio spoke quietly (he was asked multiple times to move the microphone closer and speak up), but his words rang loud and clear. He testified that Genovese was his unofficial manager, getting a cut of his fights. He showed that his official managers, John DeJohn and Joseph Netro, had to make payments to the mob totaling over $60,000 for Basilio to be granted his two title shots. He also testified that even after DeJohn and Netro had been stripped of their managing licenses by the state of New York, he was still able to hire them to help him prepare for a bout he fought in Utah. (“Doesn’t this illustrate the difficulties we are having?” Kefauver noted. “New York takes away your license… but you can act as a manager in other states.”)

Most admirably, Basilio was willing to forthrightly call out the Mafia’s influence in his sport and call for its elimination. After hearings filled with evasions and invocations of the Fifth Amendment, Basilio’s statements landed with the force of a straight right to the jaw:

[T]hose guys [Carbo, Palermo, Genovese, etc.] were making money that they were not earning and did not deserve. There are ladies present here and in all respect to them I have to contain my inner feelings but I just do not have any respect for those fellows and they do not belong in boxing. The quicker we get those fellows out, the better it is going to be for the sport.

At the conclusion of the hearings, Kefauver said that the investigation had “showed beyond any doubt that professional boxing has had too many connections with the underworld. Nothing has taken place to indicate that professional boxing ever will, on its own initiative, free itself from control by racketeers and other undesirables.” He vowed that “if strong measures are not taken to clean up boxing then it should be abolished.”

Kefauver’s Cleanup Loses by Decision

What sort of “strong measures” did Kefauver have in mind? He proposed a three-point plan to clean up the sport. First, the patchwork regulation provided by state athletic commissions was insufficient to keep the bad actors out of boxing. As with the case of Basilio’s managers, a manager or promoter who was banned in one state could just set up shop in another. Also, given the allure and profit associated with big-time fights, state commissions were all too willing to look the other way when shady figures like Carbo and Palermo were involved.

Therefore, Kefauver proposed the establishment of a temporary federal boxing commission within the Department of Justice. The commission, proposed to last for three years, would be charged with establishing standards to govern boxing and would have the power to license all participants in interstate boxing matches, including the broadcast or closed-circuit networks showing the bouts.

The other points of the plan involved making federal crimes out of two activities: being an “undercover” fight participant (that is, an unofficial promoter or manager who receives payment for a fight or fighter under the table), and attempted bribery in connection with a sporting match. These laws would facilitate federal prosecutions of the underworld figures hanging around the fight game; when combined with a three-year period of federal control and regulation, Kefauver believed, they would be enough to get the mob out of boxing.

In 1961, Kefauver first proposed a bill establishing a federal boxing commission; the bill died without getting to the Senate floor for a vote. Undaunted, Kefauver reintroduced the bill in the next Congress in 1963; however, his death that August robbed the bill of its primary champion. As late of April of 1964, however, the New York Times remained optimistic of the bill’s chances of passage, noting that the public mood toward the sport had soured due to the in-ring deaths of several prominent fighters and the highly controversial fight between Liston and Cassius Clay that February (the infamous “phantom knockout” fight). “To supporters of the bill,” the Times noted, the controversy “bolsters their argument that boxing can gain public confidence and become clean only under a Federal supervisor, who wiIl demand the disclosure of every person and every penny involved in an event. However, the bill failed to survive what the Times memorably called “the death‐trapped path” to passage.

Kefauver did score a small posthumous victory later in ‘64, when Congress passed a law making bribery in connection with a sporting contest a federal crime.

The following year, the House Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee held its own set of hearings aimed at establishing federal regulation of boxing; again, they went nowhere. To this day, the sport remains in the hands of state commissions and sanctioning bodies, and questions about its legitimacy (from allegations of rigged fights to promoters with questionable backgrounds, and more) remain.

Postscript

Basilio retired from boxing in 1961. He never became embittered by his time in the sport. “I don’t enjoy getting hurt,” he said. “But you have to take the bitter with the sweet. The sweet will be when guys recognize you on the street, say ‘Hello, Champ.’ It will always be sweet for me.” He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990, and died in 2012 at age 85.

In 1961, based in part on testimony from Kefauver’s hearings, Carbo and Palermo were convicted of conspiracy and extortion. They were sentenced to 25 years in prison, though both were released early. Carbo died in 1976, Palermo in 1996.

As for Norris, despite the fact that he admitted to perjuring himself and despite all of the disturbing revelations from the hearings, he was never charged with any crimes. He remained an NHL owner in good standing until his death from a heart attack in 1966 at age 59.

One of his last acts was to arrange for the NHL to expand to St. Louis in 1967, despite the fact that no group from the city had applied to get a team. (Why did Norris want a team there? Because he owned St. Louis Arena. Despite a somewhat rocky history, the St. Louis Blues remain an NHL franchise today.) He is a member of the Hockey Hall of Fame.

Leave a comment