Spring is my favorite season. I love the explosion of color, as flowers and trees emerge from their winter’s nap. I love the longer days, and the fact that it’s still light out after work. But perhaps most of all, spring means the return of my favorite sport, baseball.

The coming Major League Baseball season is chock full of fascinating storylines. The Texas Rangers, fresh off their first World Series title in franchise history, will try to go back-to-back. One of their stiffest competitors may be in their own state: the Houston Astros, the 2022 champs who have been to the League Championship Series seven years in a row. The Rangers and Astros share a division with the Los Angeles Angels, who will be trying to overcome the loss of two-way superstar Shohei Ohtani to the crosstown Dodgers. Over in the National League, the Dodgers will do battle with the New York Mets, another team with a huge payroll and sky-high expectations.

One thing the Rangers, Astros, Angels, and Mets all have in common: They can trace their roots back to MLB’s first wave of expansion in the early 1960s. And whether fans of those teams realize it or not, they have Estes Kefauver to thank for their existence. To understand why, let’s take a trip back to the early 1950s.

The National Pastime Confronts a Growing Nation

At the dawn of the Fifties, baseball was hugely popular, but stuck in a state of stasis. There were 16 teams in MLB – the same number that had existed since the founding of the American League in 1901. And since 1903 – when the Baltimore franchise relocated to New York, where they would become the Yankees – all of those teams had remained in the same cities, mostly in the Northeast. There was no team south of Washington, DC or west of St. Louis.

That distribution of teams made sense at the start of the 20th century. But 50 years later, many American cities had grown substantially, especially in the Midwest and West Coast, and they were hungry for big-league teams of their own.

The lords of MLB responded to this demand as they usually did, by burying their heads in the sand. Arguing that there weren’t enough quality players to stock additional teams, they refused to consider expansion. Instead, they moved a couple of the weaker teams in two-team markets. In 1953, the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee; the following year, the St. Louis Browns relocated to Baltimore and the Philadelphia Athletics went west to Kansas City.

Ultimately, though, that was a Band-Aid solution to a problem that needed a tourniquet. It did nothing to address the growing demand for major-league baseball on the West Coast. The Pacific Coast League, a top-level minors circuit, had clamored for years to be recognized as a major league; MLB basically ignored their plea. But the cities of Los Angeles and San Francisco, in particular, were getting too large for the majors to ignore. The 1950 census confirmed that LA was now America’s fourth-largest city, with San Fran in 11th. Something had to give.

And in the fall of 1957, something did. Brooklyn Dodgers Walter O’Malley, correctly perceiving a gold mine awaiting out west and fed up with his power struggle against New York city planner Robert Moses over a new stadium, moved his team to LA. He also convinced his longtime rival, New York Giants owner Horace Stoneham, to swap coasts with him, moving to San Francisco.

MLB to City: Drop Dead

The move of the Dodgers and Giants created shockwaves throughout the sport. New York Mayor Robert Wagner, having just seen the number of teams in the Big Apple drop from three to one on his watch, tasked high-powered lawyer William Shea with finding a replacement team. He quickly struck out; none of the existing teams wanted to move, and National League president Warren Giles again slammed the door on expansion, reportedly telling Shea, “Who needs New York?”

With MLB unwilling to play ball, Shea turned to Plan B: he called up highly respected longtime baseball executive Branch Rickey. Rickey was never afraid to make a bold move – he was the one who signed Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers, breaking baseball’s unofficial ban on Black players – and he and Shea made the boldest move imaginable: they planned to start another major league.

The Continental League was proposed as an eight-team circuit. When Rickey and Shea first unveiled their proposal, they had commitments from potential ownership groups in New York, Toronto, Minneapolis-St.Paul, Houston, and Denver. They later rounded out their lineup with the addition of Atlanta, Buffalo, and Dallas-Fort Worth.

Attracting interested owners was the easy part. The much bigger challenge was finding players. Unlike football and basketball, baseball’s development pipeline was controlled directly by the major leagues. Big-league clubs formed affiliate agreements with minor-league teams, creating a farm system for player development (an innovation pioneered, ironically, by Rickey). Thanks to a rule called the reserve clause, major league teams essentially controlled the rights of the players in their farm systems in perpetuity.

This clause was tied to a pair of Supreme Court decisions that exempted baseball from antitrust laws. In the 1922 decision Federal Baseball Club of Baltimore vs. National League, the court held that even though baseball teams traveled across state lines to play each other, this did not constitute “interstate commerce,” and therefore the sport was not a monopoly subject to antitrust laws.

Then in 1953, a pitcher named George Toolson, tired of being buried in the Yankees’ farm system, sued to have the reserve clause declared illegal. While the Court was sympathetic to Toolson, they voted 7-2 to uphold the decision in Federal Baseball. In their ruling, the Court – clearing its throat meaningfully and gazing in the direction of Capitol Hill – stated that if there was to be any change in baseball’s antitrust exemption, it would have to be done via legislation.

Stengel Strikes Out Senators

Suddenly in 1958, it looked like such legislation might be on the way. The Dodgers’ and Giants’ relocation to California infuriated powerful New York Rep. Emmanuel Cellar, who specialized in antitrust issues and whose district just so happened to include Brooklyn. Cellar promptly proposed a bill to revoke baseball’s antitrust exemption. This has proven to be a time-honored way to get the attention of baseball brass; as Sports Illustrated’s Roy Terrell wrote, “The very threat of congressional legislation is enough to make baseball club owners quiver like custard pudding.”

After heavy and frantic lobbying from baseball’s owners and executives, the House killed Cellar’s proposal and instead voted to exempt all pro sports from antitrust laws. (Other sports did not enjoy the same antitrust exemption that baseball had, one of several issues with the logic of the Federal Baseball ruling.)

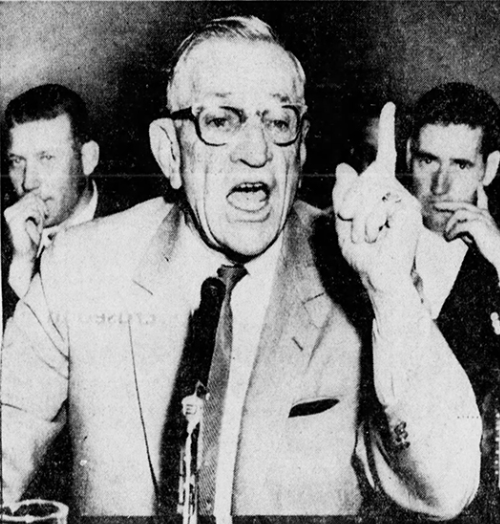

Thwarted by his House colleagues, Cellar turned to his old friend Estes Kefauver in the Senate. Like Cellar, Kefauver was skeptical of baseball’s antitrust exemption. He promptly bottled up the House bill, and instead held a set of hearings in July 1958 on whether baseball should continue to be exempt from antitrust laws.

Taking advantage of the fact that the All-Star Game was taking place in nearby Baltimore, he summoned several star baseball players to testify, along with longtime Yankees manager Casey Stengel. This turned out to be a mistake on Kefauver’s part.

Stengel was notorious for his mangling of the English language, a patois that reporters dubbed “Stengelese.” And the wily veteran skipper put on a master class in Stengelese before Kefauver’s subcommittee. One Senator after another tried to get Stengel to answer questions about whether baseball really needed or deserved an antitrust exemption, and Stengel stumped them all with lengthy strings of non-sequiturs and irrelevant anecdotes.

He claimed that the Yankees had been so dominant over the years because they had “the Spirit of 1776.” When asked by Kefauver why baseball was insistent on keeping the antitrust exemption, Stengel’s rambling answer began, “I would say I would not know, but would say the reason why they would want it passed is to keep baseball going as the highest paid ball sport that has gone into baseball and from the baseball angle, I am not going to speak of any other sport.” He referenced deceased former Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis repeatedly, and tossed in multiple stories about how he had stuck with baseball because he didn’t have enough money to afford dental college.

As a piece of gonzo performance art, Stengel’s testimony was amazing. You can read a transcript of it here. It’s like watching a knuckleball pitcher strike out a lineup of sluggers. (Mickey Mantle, who testified right after Stengel, provided the perfect punchline by claiming, “My views are about the same as Casey’s.”)

Whether this was just Stengel being Stengel, or whether baseball’s powers that be put him up to it in order to turn Kefauver’s hearings into a farce, remains a matter of debate to this day. But Kefauver wasn’t about to let Stengel’s nonsense or the sport’s reluctance put him off the case.

Kefauver Plays Hardball

In February 1959, Kefauver struck back with a bill of his own subjecting baseball and all other sports to antitrust law. Worse yet from baseball’s perspective, the bill would allow each team to control no more than 80 players. Kefauver implied that, unless MLB played nice with the proposed Continental League, he would advance his legislation. “You might say that baseball is under surveillance,” the Senator noted, “even under a shotgun.”

With Kefauver holding that shotgun to baseball’s head, the sport’s leaders piously promised to work with Rickey’s Continental League crew. Commissioner Ford Frick assured Kefauver, “I feel deep in my heart that the new Continental Baseball League will become a reality.” And baseball magnanimously announced that they would look seriously at the Continental League’s proposal – if its markets were big enough (bigger than Kansas City, the majors’ smallest), if each team had a stadium seating at least 25,000 people, and if its owners compensated the minor-league teams they would displace.

It was a clever ploy: it got Kefauver off their backs for the moment, while not committing to any definitive timeline for expansion. Rickey and Shea continued to claim that the new league was coming soon (Rickey called it “as inevitable as tomorrow morning”), and the majors responded: sure, sure…. Someday, maybe.

But Commissioner Frick screwed up this plan in January 1960. Speaking at DC’s Touchdown Club, the commissioner pronounced: “Expansion is coming, but it will not come by fiat, by pressure, or the threat of legislation.” Bold words, to be sure, but not terribly wise; Kefauver was in the audience for Frick’s remarks, and he was not amused.

Meanwhile, Washington Senators owner Calvin Griffith only exacerbated matters by announcing his intention to move to Minnesota; the looming absence of the national pastime from the nation’s capital was a headache the sport did not need.

Kefauver promptly demonstrated to baseball that he was not messing around. He revived his bill from the previous year – only this time, it limited each team to the control of just 40 players, with all the others being subject to be drafted by other teams (including, presumably, Continental League teams). Suddenly, the shotgun that Kefauver was holding the year before was cocked and loaded.

Feeling the wind at their backs, the Continental League announced that they would debut in 1961, with or without MLB’s blessing.

Baseball’s barons fussed and fumed during the hearings on Kefauver’s bill. “[H]ides firmly bound, myopia in place,” SI wrote, “they descended upon Washington, prepared to fight to the fans’ last dollar to preserve the status quo.” Commissioner Frick slammed the bill as “preposterous and vicious,” while NL president Giles blustered that it would “do great harm to a great game.” But Kefauver was undeterred.

He brought his bill to the floor in late June 1960. The majors won a small victory when a test vote to expand antitrust protection to all sports passed 45-41, and Kefauver – realizing that he didn’t have the votes – withdrew his bill. But four votes was a slim margin, and it freaked Frick and the owners out. Kefauver’s shotgun blast had missed, but it was a close call; next time, they realized, they might not be so lucky.

Baseball Calls a Truce… And Gets Civil War

Recognizing the need to make peace with Rickey’s rebels, the majors met with the Continental League’s backers and agreed to take four of their cities immediately, and the other four at a future date. The insurgents promptly took the deal, and the crisis was over.

Well, not quite over. The American and National Leagues still had to figure out how to implement the deal. And since each league was (in those days) technically independent and Commissioner Frick was a weak figurehead, things quickly spiraled out of control.

The NL, under the thumb of Dodgers owner O’Malley, struck first by voting to add the New York Mets and Houston Colt .45s, with both teams beginning play in 1962. This annoyed the AL, both because the NL unilaterally grabbed Houston – widely considered the most promising available market – and because they went to New York without consulting or compensating the Yankees.

So Yankees owners Del Webb and Dan Topping got even by approving Griffith’s move to Minnesota and expanding to Washington (to replace the departed Senators and placate Congress) and Los Angeles (to stick it to O’Malley). As an additional thumbing of the nose to the NL, their teams would begin play in 1961. Never mind that they didn’t have owners for either team, or that their decision completely ignored the agreement with the Continental League.

Well, the Continental League was dead and couldn’t fight back. But O’Malley was very much alive, and he certainly could fight back. The Dodgers owner held fast to a rule saying that no team could move into an existing major-league city without the consent of every team in the league (ignoring the fact that Frick had dubbed both New York and Los Angeles “open” for expansion earlier that year). After the AL briefly floated a cockamamie scheme where both leagues would expand to nine teams in ’61, the leagues finally settled their differences, the AL rounded up owners for their teams in DC and LA, and everything went forward more or less happily.

(The second incarnation of the Senators moved to the Dallas-Fort Worth metroplex in 1972, becoming today’s Texas Rangers. The Colt .45s became the Astros, who swapped leagues and joined the AL in 2013.)

Epilogue

Kefauver praised the outcome, but kept his eye on the ball: he was still opposed to the reserve clause. “Now that the big-league owners have faced up to their responsibilities to the public,” he told the Sporting News, “I am hopeful they now will squarely deal with the problem of player control.” He cautioned the majors that “some other steps must be taken looking forward toward an unrestricted draft.”

Kefauver’s death in 1963 meant that MLB was safe from his continued scrutiny. But baseball eventually had to face the music on player control. Outfielder Curt Flood challenged the reserve clause in court in 1969; the Supreme Court ruled 5-3 in baseball’s favor on the grounds of precedent, but declared the reserve clause subject to collective bargaining with the players’ union. In 1975, an arbitrator ruled that pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally were free agents, effectively killing the clause.

As for the old Continental League, MLB kept its agreement… eventually, kind of. Seven of the eight Continental League markets eventually got teams, everyone except Buffalo. Buffalo got to host some Toronto Blue Jays games due to travel restrictions during the pandemic, and (with all due respect) that’s as close to the majors as they’re likely to get.

(In closing, I tip my cap to the Society of American Baseball Research, whose work I relied on heavily for this post.)

Leave a comment