As I stated in this site’s introductory post, I believe that today’s political scene could really use someone like Estes Kefauver. When I tell people this, they typically ask me for examples. What are some modern-day issues where the man from Tennessee would be particularly helpful?

Last week, I read a great article by Alex Kirshner in Slate suggesting that Congress should hold hearings into Fanatics, the sports merchandising company that has recently come under fire for its partnership with Nike on the controversial redesign of Major League Baseball uniforms.

As Kirshner notes in the article, Fanatics has gobbled up a huge share of the apparel and merchandise market across many major sports, racking up huge profits despite a reputation for questionable quality and poor customer service. He concludes that “it’s time for the federal government to get involved, ideally in a way that has some teeth. But let’s settle first for something much easier to achieve: a glitzy, entirely performative congressional hearing that lights a fire under the company’s collective ass.”

While reading the article, I kept thinking: Man, this would have been right up Kefauver’s alley.

Kefauver was the master of attention-grabbing Congressional hearings. His televised Senate hearings into organized crime captivated the nation, spawning multiple books and movies and making Kefauver himself a household name. Subsequent probes into juvenile delinquency, the steel and automotive industries, and prescription drugs also attracted plenty of headlines and focused attention on important issues of the day. (He even held hearings into Major League Baseball in the late ‘50s, which will be the subject of a future post.) Kefauver had such a knack for drawing attention to his hearings that his Senate rivals resented him for it, and sometimes even tried to block him from holding them for fear of boosting his Presidential prospects.

But contrary to the jibes of his detractors, Kefauver wasn’t just a publicity hound. His hearings were designed to arouse public attention and get the people clamoring for action. And when it came to government action with some teeth, he was ready with legislation to address the problems he’d identified through the hearings.

The Fanatics issue would have been of particular interest to Kefauver because it touches on matters of antitrust and monopoly, issues near and dear to the Senator’s heart. As Kirshner writes, “Fanatics looks an awful lot like a monopoly. The reason it’s hard to be definitive about it is that the mechanics of Fanatics’ dominance are novel.”

Fanatics doesn’t just make sports apparel; they also run the online and brick-and-mortal retailing for several teams and leagues. They also control the licensing for a number of popular team names and logos. So rival apparel manufacturers need to deal with Fanatics in order to be allowed to produce team-branded apparel, which they then would sell at Fanatics-owned outlets. As Kirshner writes, “A cynic might think that this puts obvious pressure on the smaller apparel company to sell its products on Fanatics’ platforms at terms amenable to Fanatics.”

Kirshner also notes that after Fanatics won the contracts to produce baseball trading cars and uniforms away from established rivals, they then bought those rival companies, something that surely would have caught Kefauver’s attention.

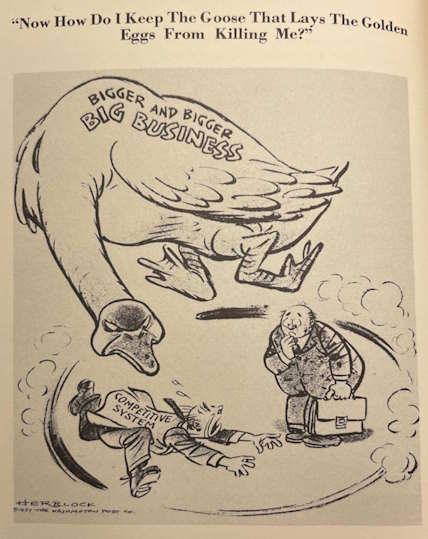

None of these things technically constitutes a monopoly, but as Kefauver knew, you don’t have to be a literal monopoly to behave like one. Fanatics’ situation bears some resemblance to the American auto industry of the mid-1950s. In theory, the Big Three (plus American Motors) were competitors. But in practice, General Motors had such an enormous market share that they were able to essentially dictate practices, from pricing to styling, that the rest of the industry was essentially bound to follow.

Similarly, Fanatics is in such a position of power in sports apparel that they can essentially dictate terms to their would-be competitors. (Another common thread between Fanatics and 1950s GM: they’re able to roll up massive profits while cutting corners on quality, since they control so much of the market that they can’t be effectively challenged.)

If anyone could have devised a revision to antitrust law to thwart companies like Fanatics, it would have been Kefauver. He was the Senate’s acknowledged expert on the subject, and he was intimately familiar with the tricks that corporations pulled to consolidate power.

Fanatics’ moves in the sports apparel industry could be considered “vertical integration,” where one company controls multiple portions of the supply chain for the same product. A classic example would be a company buying up its suppliers, and preventing other companies from getting the materials they need to make the same product. The Cellar-Kefauver Act of 1950 cracked down on precisely those sorts of vertical mergers.

Couldn’t team names and logos be considered the “raw material” needed to make branded sports apparel? And therefore, should an apparel manufacturer also be allowed to control access to those key properties? Or at the other end, should Fanatics be allowed to run the outlets where their competitors are selling apparel alongside theirs?

The example of Fanatics winning the baseball-card business from Topps, or the baseball uniform business from Majestic, and then buying up those companies feels similar to another practice outlawed by the Cellar-Kefauver Act, where a company bought out a rival by purchasing its assets. MLB’s contracts with Topps and Majestic were so central to their respective business that Fanatics essentially gutted them by winning the business, after which they bought up their rivals at (one would imagine) a discounted price.

While Kefauver was working with staffers to devise legislation to close the loopholes exploited by a company like Fanatics, he could whip up public outcry with the hearings. As Kirshner writes, “Batting around a CEO for an afternoon is easy. Maybe he’ll even say something that one of his company’s competitors can cite in a legal filing.”

Even if the CEO doesn’t wind up sparking a lawsuit with a poor turn of phrase, he might wind up fueling public anger. Certainly, Kefauver was well-versed in getting the rich and powerful to say ridiculous things. For instance, during the steel industry hearings, when he forced executives to defend price collusion by claiming that companies offering identical prices was somehow a hallmark of free enterprise. Or the time he got a pharma CEO to admit that they had no incentive to reduce prices on prescription drugs because they couldn’t make more sick people. Or the many times he cornered corrupt politicians and sheriffs into bumbling and fumbling through explanations of their newfound wealth during the organized crime hearings.

These people weren’t used to having to justify themselves and their practices to the average citizens. When Kefauver made them do so in his hearings, their responses were exposed as tortured, illogical, and absurd.

When a company like Fanatics is able to hoover up massive profits while making professional uniforms look like cheap knockoffs and stiffing customers left and right, it rightly enrages the average American. All the more so because we feel helpless; it seems like companies are able to get away with charging more and more for worse and worse products and there’s nothing we can do about it.

Estes Kefauver was beloved because he made average Americans feel like there was something we could do about it, that we didn’t just have to sit back and take whatever monopolistic companies felt like giving. He made the average American feel like they weren’t alone, that they had a powerful ally to do battle against monopolistic corporations, corrupt politicos, crime bosses, and other wrongdoers in American life. Someone who could turn on a public spotlight to expose evil, and then take action to address it.

When I say that we need someone like Estes Kefauver today, this is what I’m talking about. I hope that some of today’s elected officials will read Kirshner’s article and be motivated to follow in Kefauver’s footsteps.

Leave a comment