One of the challenges Estes Kefauver faced in the early stages of his Senatorial career – and in his Presidential runs – was a troubled relationship with his more senior colleagues. There were a number of reasons for this: his indifference to the rules of the Senate “club,” his stubborn independent streak, his unwillingness to toe the Southern line on civil rights, his impatient ambition, the embarrassment his organized crime probe caused to Democratic leaders.

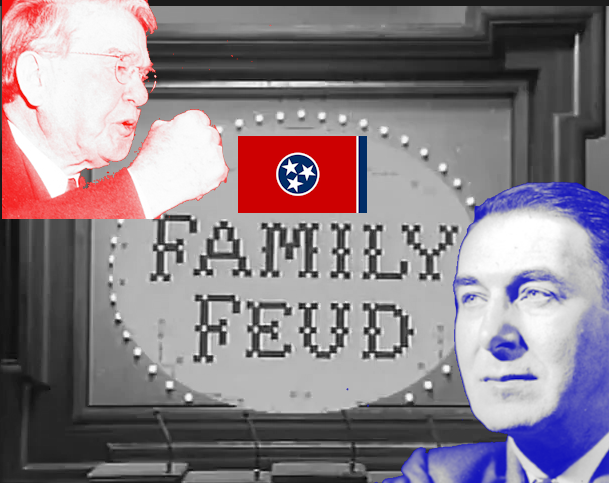

Perhaps his most difficult Senatorial relationship, however, was right in his own backyard. During the first four years of Kefauver’s time in the Senate, his senior colleague from Tennessee was the legendary Kenneth McKellar. And McKellar loathed Kefauver. During their four years of shared Senate service, McKellar waged a campaigned of sustained hostility toward his junior colleague, and did whatever he could to undermine Kefauver with both his fellow Senators and the White House.

Why did he hate Kefauver so much? Well, to answer that question, you need to understand Kenneth McKellar.

“Grandpa of the Senate”

To call Senator McKellar a throwback to an earlier era would be an understatement. He was born just four years after the end of the Civil War. When he first arrived in Congress in 1911, Estes Kefauver was just eight years old. By the time Kefauver joined the Senate, McKellar was in the middle of his sixth term, earning the nickname “Grandpa of the Senate” from journalist Drew Pearson. He regularly appeared in the Senate wearing “morning attire” consisting of a frock cost, vest, and striped trousers.

Despite being a proud son of the South, McKellar operated much like the boss of a big-city political machine like Tammany Hall. In the words of Knoxville journalist Ray Hill, “Senator McKellar commanded an army of patronage appointees in the State of Tennessee and presided over a political organization that stretched from one end of Tennessee to the other. From Mountain City to the banks of the Mississippi River in Memphis, there were literally tens of thousands of Tennesseans for whom Senator McKellar had done a favor at one time or another.”

Given that Kefauver entered politics as a reformer and McKellar was the symbol of the establishment – and that Kefauver was a proud liberal while McKellar leaned conservative – it would be easy to think that was the cause of their antagonistic relationship. But that was only incidentally true. As was usually the case with McKellar, the source of the friction was much more personal.

One other trait that Senator McKellar shared with the typical urban machine boss: he was the sort of person you didn’t cross. He had a long memory and was a virtuoso at nursing a grudge. If you got on McKellar’s bad side, he would not forgive and he would not forget.

Senator McKellar had long had a reputation as an irascible character, and he only grew crabbier as he aged. In August 1950, journalist Jack Anderson recounted a notable clash between McKellar and Missouri Rep. Clarence Cannon (another famously temperamental sort) during an Appropriation conference committee meeting. In response to critical comments from Cannon over a spending disagreement, McKellar launched into a tirade calling Cannon blind, stupid, and pigheaded. Cannon rose from his chair and declared “I’ve taken all I’m going to,” at which point McKellar grabbed the gavel and attempted to whack Cannon over the head with it. It took two other Senators to get the gavel away from him.

In summary, McKellar was not the man you wanted for an enemy. Kefauver would learn this lesson the hard way.

Getting Off on the Wrong Foot

When Kefauver first came to Congress, McKellar was perfectly cordial toward him. In 1940, the senior Senator predicted that one day, the young Congressman would “be one of the great leaders of in the state.”

Kefauver first drew McKellar’s ire by opposing his plans for the Tennessee Valley Authority. As mentioned in Part 1 of my series on TVA, the Senator saw the agency as a golden opportunity to add a new division to his patronage army. He waged a years-long political (and personal) battle with TVA chair David Lilienthal for control of the agency.

Kefauver not only sided with Lilienthal during these battles, he repeatedly rallied a bloc of House members to thwart McKellar’s schemes from becoming law. Although Kefauver believed he was just standing up for the TVA, McKellar (you’ll never believe this) took it as a personal affront.

In 1946, Kefauver compounded the offense by considering a primary challenge to McKellar. Although he ultimately (and wisely) declined to skip the race, he (unwisely) endorsed Ned Carmack, who did decide to primary McKellar. Carmack’s challenge was doomed from the start, and Kefauver’s vocal support only served to infuriate the senior Senator. McKellar sought revenge by backing a primary challenger in Kefauver’s Congressional district; however, the best they could do was a hapless chap named Pup McWhorter, and Kefauver cruised to reelection.

Then in 1948, Kefauver did run for the Senate, defeating incumbent Tom Stewart, an amiable sort who generally voted as McKellar told him to. When either man liked it or not, Kefauver and McKellar would now be colleagues.

Mess With the Bull, Get The Horns

Kefauver wisely recognized the need to at least try to patch up relations. He called on McKellar and gave him what the older man described as “a long line of unnecessary flattery,” and they agreed – at least in theory – to let bygones be bygones. Kefauver supported McKellar’s successful bid to become President Pro Tempore of the Senate, and McKellar escorted Kefauver to the rostrum to be sworn in as a new Senator.

Their truce lasted all of about three weeks.

Things fell apart over a federal marshal position in Middle Tennessee. McKellar recommended a man named Reed Sharp for the appointment. Kefauver opposed the choice, calling Sharp a “Dixiecrat.” Kefauver’s choice got the appointment.

If you mess with the bull (in this case, McKellar’s patronage appointments), you get the horns. McKellar wrote his junior colleague a blistering letter reading, “Several Tennessee newspaper people have told me that you are very anxious to cooperate with me, and the intimation was that I had refused to cooperate with you. I wonder what your idea of cooperation is? Is it that you do all the operating’ and leave the ‘co’ to me?”

Naturally, McKellar wasn’t going to let the matter drop there. He proceeded to write President Truman a letter ripping Kefauver, beginning with the words: “I am informed that Mr. Kefauver is claiming to have helped you in Tennessee. This claim is without the slightest foundation.” It went downhill from there.

From that point on, McKellar went out of his way to ridicule and defame Kefauver at every opportunity. He regularly referred to his junior colleague as “Cowfever” (a derogatory nickname also used by President Truman) and gleefully told associates that Kefauver was “about as stupid as they come,” recounting a supposed incident from the 1944 Democratic convention in which Kefauver supposedly referred to Thomas Jefferson as a President from Tennessee. (It’s certainly possible that the gaffe-prone Kefauver once scrambled the names of Jefferson and Andrew Jackson.) McKellar also proudly told visitors that on one occasion, he “ran [Kefauver] out of my office with a came.”

Hatfields vs. McCoys

The relationship between the Tennessee Senators reached an all-time low in the autumn of 1951. There was a plan to add a new federal judge in the state. McKellar wanted the judge to be based in Middle Tennessee; Kefauver, noting the population explosion in the Memphis area, proposed a roving judge who could split time between Middle Tennessee and West Tennessee. Kefauver’s approach was preferred by the people at home, but McKellar wasn’t about to let his constituents – or his junior colleague – tell him what to do.

As a member of the Judiciary Committee, Kefauver had a leg up in this dispute, and he persuaded the committee to back his recommendation. In response, McKellar sent a letter to the other Judiciary Committee members, ripping Kefauver and imploring them to support his approach to the judiciary, couching it (hilariously) in the guise of “keeping politics out of judicial affairs.”

Time and age had not dulled McKellar’s poison pen one bit. He began with the following barb: – “As a member of the Policy Committee of the Senate, I secured for Mr. Kefauver a place on the Judiciary Committee. I apologize for that.” From there, he went on to attack Kefauver’s proposal, saying: “For some unaccountable reason, unless it be politics, Mr. Kefauver turned up not long ago wanting to make that judge a roving judge… and in some manner unknown to me, he claims to have secured a majority of the Committee in favor of his amendment.”

(One common thread throughout McKellar’s feuds and harangues: He always assumed that his adversaries’ positions were driven largely by political considerations. He lobbed the same accusations at David Lilienthal during the TVA feud, as though Lilienthal were a rival officeholder. Whether or not there was any truth to McKellar’s accusations, it’s certainly an illuminating look at his own mindset.)

Despite McKellar’s counteroffensive, the Judiciary Committee voted for Kefauver’s proposal. Undaunted, the senior Senator took matters up with the whole Senate. He made a lengthy speech attacking both Kefauver and the proposal. When Kefauver rose to defend himself, McKellar kept interrupting him, despite Kefauver’s repeated insistence that he would not yield the floor.

It was at that point that Senator William Langer of North Dakota popped up to inquire, “I should like to know which Senator from Tennessee represents the Hatfields and which one represents the McCoys?”

In the end, McKellar won the battle, getting the full Senate to support his proposal by a vote of 60-19. He was no more gracious in victory than he was in defeat. McKellar instructed his staff that they were under no circumstances to so much as mention Kefauver’s name in the office. Anybody who did so was summarily fired.

The Old Man Goes Down Swinging

Unfortunately for the senior Senator, the end of the road was close at hand. He was up for reelection in 1952, at the age of 83. Even longtime allies like Memphis political boss Ed Crump advised him to retire gracefully, knowing that both his physical and mental health were failing. (A vicious rumor circulated that a confused McKellar once urinated on a column in the Senate rotunda, mistaking it for the bathroom.) But ornery as ever, McKellar decided to run again anyhow.

He was primaried by Rep. Albert Gore. McKellar’s health barely allowed him to make it back to visit Tennessee, much less mount an active campaign. He relied on having his campaign staff blanket the state with signs bearing his slogan, “The thinking feller votes McKellar.” (His opponent countered with the slogan “Think some more and vote for Gore.”) Possibly learning from Kefauver’s experience, Gore decided not to attack McKellar during the campaign; in fact, he rarely mentioned the Senator’s name.

In the end, voters opted for Gore’s youth and vitality over McKellar’s long record of patronage and pork-barrel. With that, a career of over four decades in public office came to an end. His life would come to end five years later, at the age of 88.

Having the more like-minded Gore working beside him made Kefauver’s working life somewhat easier, but his relationship with Senate leaders remained strained even after McKellar’s departure. Certainly, Kefauver’s own approach to politics – all of the factors I mentioned in the introduction – contributed a good deal to that.

But it’s only reasonable to wonder if his Senatorial career might have gone more smoothly if his reputation hadn’t suffered from four years of “friendly fire” at the hands of his senior colleague.

Leave a comment