Fans of American cars (and I count myself among them) often ask themselves how the industry lost its way. In the 1950s and early 1960s, American cars dominated the market, with General Motors leading the way. By the 1970s, however, things had changed. The Big Three were losing market share to imports from Europe and Japan. By decade’s end, Chrysler would be bankrupt, Ford nearly so, and GM was limping along.

How did a once-thriving industry slide so quickly? Estes Kefauver provided some of the answers in his 1964 book “In A Few Hands,” which studied the issue of economic concentration in key industries. His insights into the auto industry would prove prescient; unfortunately, the Big Three weren’t paying attention, ultimately to their detriment.

Kefauver’s book pointed out the many ways in which the Big Three’s stranglehold on the industry allowed them to pad their profits at the expense of consumers. In a previous post, I described Kefauver’s critique of the styling wars in the auto industry. This time, we’ll look at his comments on the size of cars, and the threat of foreign competition.

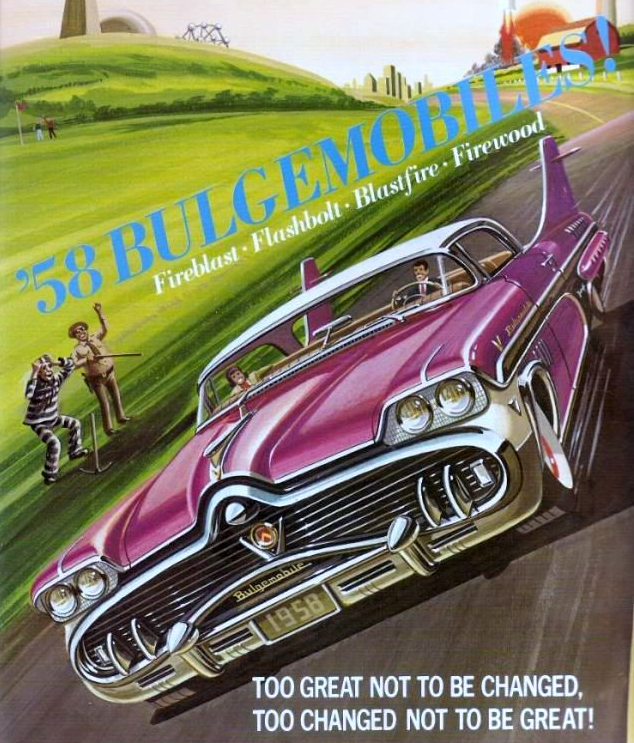

Kefauver’s subcommittee held hearings on the auto industry in 1958. The late ‘50s saw an explosion in the size of American cars. “Longer, lower, wider” was the order of the day, a trend that quickly reached the point of absurdity. (In the ‘70s, Bruce McCall brilliantly satirized the cars of the period with his “Bulgemobile” ads in the pages of National Lampoon; see the featured image of this post for an example.)

The automakers claimed, as always, to be responding to consumer demand. Kefauver, however, argued that many consumers actually wanted smaller and more efficient cars. (On the brilliant Curbside Classic site, Paul Niedermeyer makes the case that this was especially true for women, many of whom began driving for the first time in this era and found typical big cars unwieldy to drive and park.) The Big Three, however, ignored this demand in pursuit of higher profits.

They weren’t called the “Big Three” for nothing.

Frustrated consumers turned instead to smaller cars made by smaller American companies, such as the Rambler and the Studebaker Lark – as well as those made by foreign companies. Kefauver noted that “foreign imports of small cars were making threatening inroads in the United States market. From 1% of new passenger car registrations in 1955, the figure for this group had risen to over 5% by 1958 and was to reach 6½% in 1959. Yet American cars, bigger and fancier, were being produced each year. Who dictated these styles?”

Belatedly taking notice, the Big Three finally introduced a new class of compact cars in 1960, cars like the Ford Falcon, Chevy Corvair, and Plymouth Valiant. These cars proved hugely popular, and appeared to stem the tide of the imports (along with cars like the Rambler and Lark). As Kefauver noted in the pages of “In A Few Hands”:

The introduction of the compact car represented a triumph of public demand for smaller and more economical instruments of transportation. The burgeoning of foreign imports and the success of American Motors were a direct refutation of the GM position… [I]n a flurry of activity, the large automobile manufacturers suddenly reversed their accustomed course and adopted the philosophy of their smaller, upstart competitors.

The Big Three finally go on a diet.

And yet, story after their introduction, the compacts began to grow as well. Kefauver wrote that “the new compacts had hardly made their appearance before the pressure began anew for bigger and fancier versions. At the present time the major manufacturers are vociferously vying with each other in P.T. Barnum’s term for ‘the biggest little midgets in the world.’” He cited the Corvair Monza Spyder as an example; the Monza had a supercharged engine and was advertised as being “too roomy to be a compact.”

Cars like the Falcon and Valiant continued to grow in size and power, once again leaving a vacancy at the lower end of the market. Kefauver warned about this in the pages of “In A Few Hands”:

The public’s genuine interest in smaller and more economical cars is indicated by the fact that so-called compacts now have over a third of US sales; counting foreign imports – composed almost entirely of small models – the figure is around 40 percent. Sales of imported cars appear to be on the rise again; they are edging up to the levels prevailing at the time that the American companies made the defensive move of introducing their own smaller models. The increased popularity of imports may reflect the growing realization by United States consumers that the “biggest little midget’ is something of a contradiction in terms.

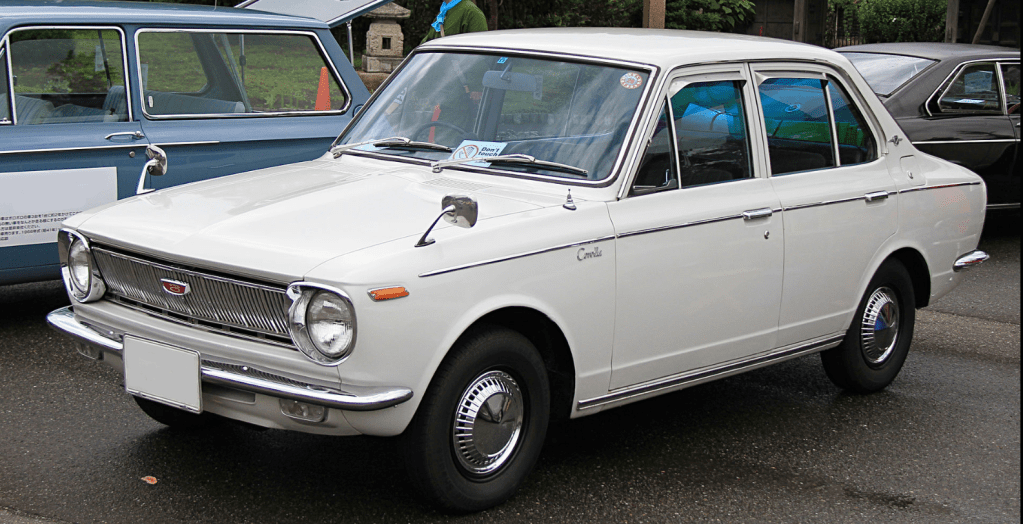

Imported car sales would only rise further from the time that “In A Few Hands” was published. And where the first wave of imports were from Europe, the American market would soon see an invasion from the East. The Toyota Corolla made its US debut in 1968; by 1973, it was selling over 100,000 units a year in America. The oil shocks of the 1970s made fuel efficiency a priority for many buyers, but the imports were also smaller and better built than the American cars of the day.

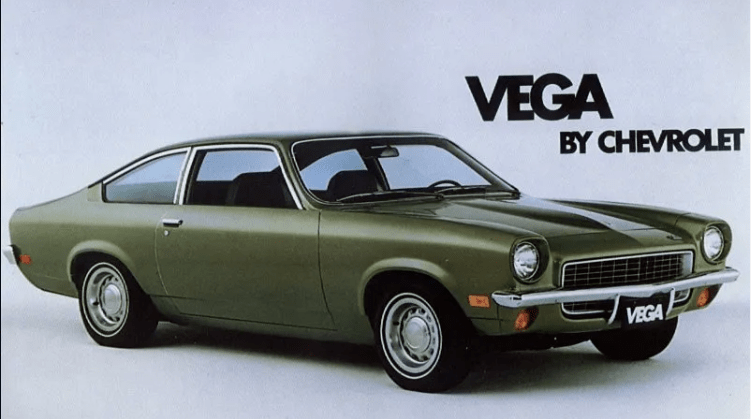

Once again, the Big Three were slow in responding to consumer demand. It didn’t help that two of Detroit’s most prominent entries in the new subcompact class were disasters: the Ford Pinto (with its exploding gas tanks) and the Chevy Vega (with its self-destructing aluminum engine and poor build quality). Buyers were left with the impression that the Big Three didn’t know how to – or didn’t care to – make a quality small car.

Not great, Bob!

If Kefauver had been alive to see the rise of the Japanese car industry in the US, he wouldn’t have bene surprised. Though he was too gracious to say “I told you so,” no one can say he didn’t try to warn the Big Three what was coming.

Leave a comment