Having grown up near Washington, DC, I’m very familiar with the city’s long and tortured quest for statehood. The modern statehood movement has been active since the 1980s; since 1993, advocates have introduced bills in Congress on an annual basis to make DC a state, although the bills have never come to a vote.

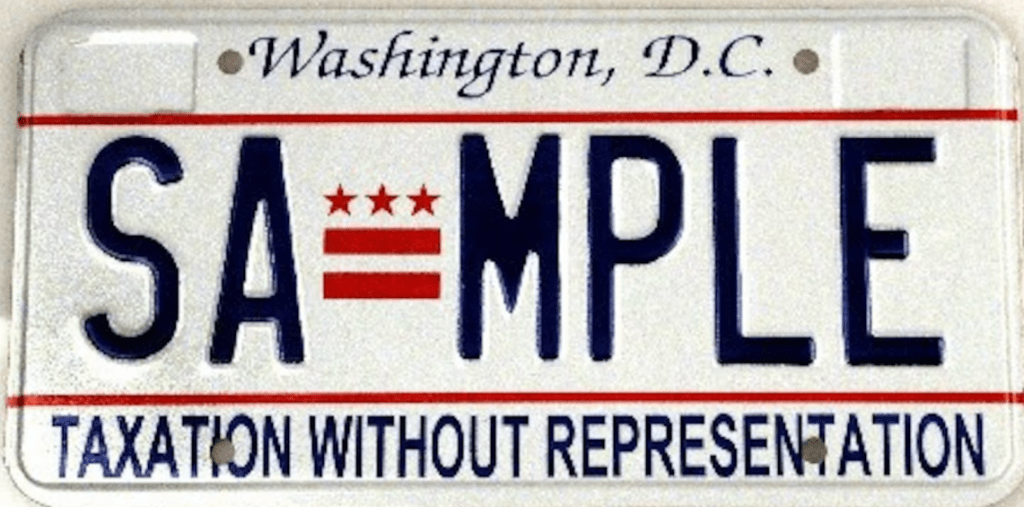

In the 21st century, city leaders have embraced the cause. The city added the “Taxation Without Representation” slogan to its license plates in the year 2000. Mayor Muriel Bowser held a citywide referendum on statehood in 2016; it passed with 85% of the vote. Odds are, if you see a DC politician wearing a sports jersey these days, the jersey will bear the number 51, calling for DC to be the 51st state.

For instance, here’s Mayor Bowser at a playoff rally for the Washington Capitals hockey team in 2016:

Here’s then-Mayor Vince Gray in 2011 at the opening day of the DC Rollergirls roller derby season:

I’m a supporter of DC statehood. I understand the arguments against it and the logistical challenges associated with it. But fundamentally, I think it’s unfair that DC residents don’t have full control over local affairs, and that they’re denied voting representation in Congress. (Bad enough that DC residents have to put up with Congress in their backyard; not having a vote there just rubs salt in the wound.)

You know who else felt this way? Estes Kefauver! (You probably guessed that’s where we were headed, given the title of this blog.) Kefauver was for DC self-determination before it was cool.

Kefauver made the case for extending democracy to our nation’s capital in his 1948 book A Twentieth Century Congress. At the time, DC’s residents were even less in control of their own fate than they are now.

Washingtonians had no ability to govern their own affairs; Congress took away DC home rule in 1874 in a snit over what they perceived as profligate spending by the city government. Instead, the city was a word of the District of Columbia Committees in the Senate and House. DC citizens also had no vote in federal elections. Since the Constitution only gave federal rights to the states, and DC wasn’t a state… sorry, kids, no voting for you.

Kefauver included DC self-determination in his book as a means to improve Congressional efficiency, rightly pointing out that members of Congress had more important things to do than manage the city’s municipal business. He sardonically described the workings of the District of Columbia Committee as “congressmen, in session assembled, acting as town councilmen and arguing over issues like the number of taxicabs to be licensed or the reinstatement of policemen fired from the local force. These trivia produce lengthy and heated debate. The penchant of a national legislator to act at times like a spoiled child is painfully exposed.”

But this wasn’t just a matter of improved efficiency for Kefauver. He made the case that self-government for DC was a matter of fairness and justice for its citizens. He wrote, “District residents should be given the right to vote, elect their own officials, participate in national elections, and be represented in Congress.”

Within the pages of A Twentieth Century Congress, Kefauver described the people of the District as “a special group of political orphans illogically deemed unable to exercise self-government and thrust, like unwanted stepchildren, in the lap of Congress.” He added that “[t]he manner in which Congress attempts to govern the District of Columbia is indefensible. The nearly one million residents of Washington are in the same category as felons, aliens, incompetents, and federally supported Indians.”

Anticipating a favorite talking point of the modern DC statehood movement, Kefauver wrote:

“These citizens pay local and federal taxes at rates exceeding those of many states… But they have no voice in the spending of this money. Taxation without representation was one of the things that made Americans fight the Revolution. These Washingtonians perform all obligations of citizenship, jury service, full responsibilities under Selective Service, and so on, but they are foreigners as far as the basic right to control their own destiny is concerned.”

He also accused Congress of mismanaging the city, noting that DC lacked “[p]ublic services now taken for granted in many municipalities, such as a modern jail or juvenile court system, to name two,.. The city is neglected as an orphan and treated like the proverbial stepchild. The blame rests squarely on Congress.”

While Kefauver didn’t specifically cite DC’s then-emerging status as a majority-black city as a reason for Congressional attitudes toward city self-government, he didn’t ignore the point either.

He noted that hen the chairmanship of the Senate District of Columbia Committee opened up in 1945, Senators “ran like frightened hares to the nearest legislative refuge” with the exception of Mississippi’s Theodore Bilbo, who accepted the chairmanship “to the almost unanimous dismay of the local citizenry.” Bilbo was a notorious segregationist and Ku Klux Klan member who used his post to treat DC like a plantation.

Sadly, as happened so often throughout Kefauver’s political career, his arguments largely fell on deaf ears. It wasn’t until 1961 that DC got the right to vote in presidential elections, courtesy of the 23rd Amendment (which emerged from a Senate resolution originated by Kefauver). Home rule wouldn’t arrive until 1973. The House and Senate District of Columbia Committees, which Kefauver wanted to abolish, are still around. And of course, the District still has no voting representation in Congress. (They do have a non-voting delegate, Eleanor Holmes Norton).

If Kefauver’s Congressional colleagues had listened to him 75 years ago, we wouldn’t need those license plate slogans and #51 jerseys today. Washingtonians would have the same rights and privileges as their fellow Americans, just as it should be.

Leave a comment