(featured image by Daniel Johnson)

Boss E.H. Crump’s newspaper ad attacking Estes Kefauver during the 1948 primary (the “pet coon” ad) contains a number of attacks – racist appeals and accusations of Communist sympathies – that we understand today. However, the ad makes repeated references to Vito Marcantonio, claiming that he and Kefauver are “birds of a feather.” Who the heck was Vito Marcantonio, and why were the voters of Tennessee supposed to care whether Kefauver was allied with him?

To answer the second question: Think of modern GOP attack ads featuring left-wing figures from “The Squad” like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, and Rashida Tlaib. Vito Marcantonio was essentially the ’40s version of The Squad: a boogeyman to convince voters that more moderate Democrats are actually dangerous radicals in disguise.

Marcantonio was born in 1902 (a year before Kefauver) in the East Harlem section of New York City. East Harlem has long been a rough area; at the time Marcantonio was born, it consisted of several crowded immigrant neighborhoods – notably Italian, German, Irish, and Jewish – surrounded by “gasworks, stockyards, and tar and garbage dumps,” as described in the 1999 book “Gotham.” After attending high school in Hell’s Kitchen and getting a law degree from NYU, he went to work in private practice.

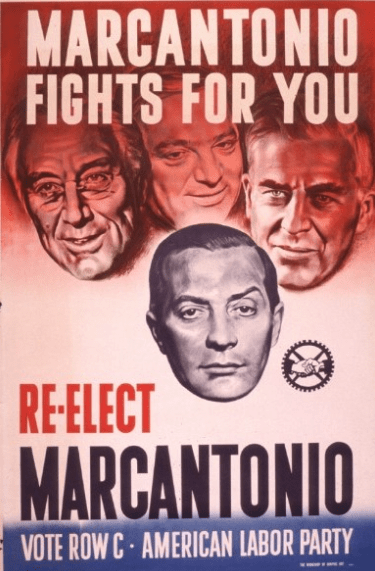

At the same time, he also became involved in politics. After hearing Fiorello LaGuardia speak at his law school, Marcantonio began managing LaGuardia’s congressional campaigns. In 1934, when LaGuardia decided to run for mayor, Marcantonio ran for Congress (as a Republican, following his mentor’s example) to represent East Harlem. He won, but lost re-election in 1936 to James Lanzetta, the man he’d beaten two earlier. In 1938, he ran again under a new party banner – the American Labor Party – and won the seat back, holding it through six more terms.

In Congress, the diminutive Marcantonio used his booming voice to advocate for the poor, the working class, and the dispossessed. By this time, East Harlem was home to a large Puerto Rican population, and Marcantonio – who was fluent in both Spanish and Italian – represented them as fervently as he did the other immigrants in his district, authoring multiple bills for Puerto Rican independence. He spoke up in support of labor unions, support for the poor, and civil liberties. He was a champion of civil rights, sponsoring bills to outlaw poll taxes and make lynching a federal crime. Fighting against a Congress he considered “hopelessly reactionary,” he fought to expand and extend the benefits of the New Deal beyond even what FDR proposed.

Even as he became a national symbol for left-wing causes, Marcantonio never forgot his home district. He threw open the doors of his district office to help constituents find jobs, navigate the immigration process, fight eviction notices, and more. He even personally delivered coal to tenements in the wintertime.

He fought a proposal to gentrify East Harlem, thundering: “The East River is our river. We were born on its banks. We learned to swim in that river. We have lived and suffered alongside its banks. We have had to smell it in the hot summer days. Now that the river has been cleaned, and now that the land alongside of it is available we want that river to ourselves.” He made sure that public housing units, not luxury apartments, were built along the river.

He was so popular in he district that he regularly cross-filed on the Democrat, Republican, and ALP lines – and won the nomination of all three parties.

By the time of Crump’s ad, however, Marcantonio’s Congressional colleagues were sick of him. Most Southerners detested his civil-rights stances, and Democrats everywhere were alienated by his insistence that the New Deal didn’t go far enough and his repeated harangues against the “unjust economic and social system which has failed.” More crucially, his vocal defense of Communists and left-wing radicals made him a pariah as the Cold War heated up.

In 1947, New York outlawed Marcantonio’s cross-filing maneuver with the Wilson Pakula Act. He managed to win reelection in 1948 anyway, but his vote against US involvement in the Korean War seems to have been the last straw. The Democrats, Republicans, and the Liberal Party teamed up in 1950 to support Marcantonio’s opponent, James Donovan, and the New York Times ran three straight editorials denouncing the Congressman. With all those forces allied against him, Marcantonio finally lost and returned to his law practice.

Four years later, while preparing a run for his old seat, Marcantonio suffered a heart attack coming up out of the subway in Lower Manhattan and died at age 52. He received the Catholic last rites but, despite his lifelong faith, he was denied a Church burial due to his suspected Communist sympathies.

So, one might wonder: Was Vito Marcantonio actually a Communist? He denied it, saying: “I disagree with the Communists. I emphatically do not agree with them, but they have a perfect right to speak out and to advocate communism.”

That said, his political positions were far to the left, and he was clearly sympathetic to communistic and socialistic ideas. And while his American Labor Party was originally a coalition of various pro-labor leftist groups, by the mid-1940s it had been taken over by Communist factions, and many of its original members defected to join the Liberal Party for that reason.

While it may not have been totally accurate to call Marcantonio an “ox-blood-red Communist,” as Crump did in his ad, the description (unlike with Kefauver) wasn’t completely unfounded. (I should point out that there is no evidence that Marcantonio was a spy or a Soviet loyalist.)

I find it fascinating that Vito Marcantonio was enough of a national figure that Crump found him worth mentioning in a Tennessee political ad. But it goes to show that “nutpicking” was a thing long before we had a term for it.

For the record, Marcantonio was asked about Boss Crump’s accusations about Kefauver. His response: “[A]lthough I have respect for Kefauver’s honesty, personal integrity, and ability, I would say that at rock bottom he is a conservative.”

Leave a comment